Antoni Gaudi's Casa Batllo and Casa Mila

Two Extraordinary Residences in Barcelona

By: Mark Favermann - Jan 31, 2010

Antoni Gaudi's genius can be seen in much of his work. Two residential projects in particular illustrate the mastery of his unique sensibility, the family mansion of Casa Batllo and the apartment building Casa Mila also known as La Pedrera. Located in central city Barcelona a few blocks from each other, both buildings are now partially or wholly museums and are each a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Casa Batllo is the former family home of the wealthy Batllo family. The residential structure had been rather conventionally built in 1875 on the most chic Barcelona boulevard, Passeig de Gracia, in the heart of the city, favored by the upper class. Next door to the home was another more impressively ornamental residence, Casa Amatller, which was spectacularly designed by Puig i Cadafatch, another prominent and fashionable Moderniste architect.

Senor Batllo did not want to be overshadowed, so he commissioned Antoni Gaudi in 1904 to creatively enhance his house. Thus, Batllo was involved in early 20th Century one-upmanship. The resulting 1906 edifice is an example of Gaudi at the height of his creative powers. It is a complete project of his personal, unique vision, both on the inside and outside. Gaudi was assisted by Josep Maria Jujol.

The local name for the building is Casa dels Ossos or House of Bones. There is a visceral even skeletal, organic quality to the structure. Like other Gaudi projects, it is only broadly identifiable as a Moderniste or Catalan Art Nouveau style because of Gaudi's unique approach. The facade was made from sandstone that had thin carved columns in plant motifs. The ground floor has unique tracery, (stonework around the windows), irregular oval windows, and skeletal, flowing sculpted stonework. There are few if any straight lines. There is a compositional joy in the building, an architectural acknowledgement of the pleasure in the total design.

The boldly decorated front of the building is reminiscent of an impressionist painting with a mosaic of broken ceramic tile (trencadis) that flows from shades of golden orange into greenish blue hues. Like many of Gaudi's structures, the roof is like the arched back of a dragon.

The dragon was one of Gaudi's favorite mythical creatures. It was also a strong nationalist symbol of Catalonia as St George and the Dragon is an icon of the region. St George was the patron saint of Catalonia. It has been postulated that the rounded roof feature to the left of center, terminating at the top in a turret and cross, represents Saint George's sword thrust into the dragon's back.

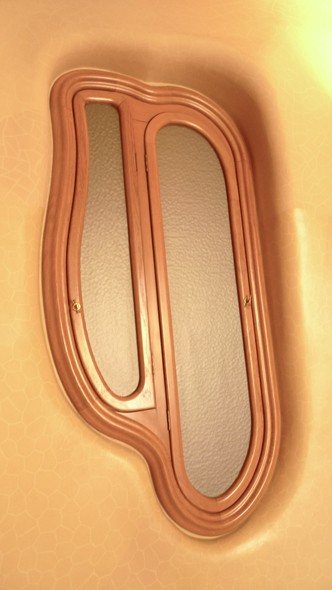

Organic shapes and natural elements are the thematic design motif of Casa Batllo. These undulating shapes and forms can be seen throughout the exterior and interior spaces. Highly decorated and colorful usually by application of trencadis or broken ceramic tiles, not only was this organic styling similar to other Art Nouveau decor, it was based upon plant, mushroom or even sea life configurations. The woodwork, shaped windows and even stonework columns in the house were all organic shaped.

The architect organized the common areas of the house in such a way as to illuminate and ventilate all rooms. This also underscored a fluid connection between the exterior and interior. A mixed use area in every sense, the ground floor was organized into three zones: access to the residence, access to the shop/retail space and an entrance to the parking area.

The interior patio which included the lift and stairs was inspired by the depths of the ocean and Gaudi's love of the Mediterranean Sea. He used up to five tones of blue tiles of varying glossiness which got lighter as they went down from the skylights. This allowed for a more regulated, homogeneous light.

The main floor of the house was a spacious arrangement of rooms that are bright and open. Nature's curves add to the undulating features that make the space welcoming and functionally brilliant. Each door and window are uniquely shaped. The woodworking and elegant craftsmanship is exquisite

The stair railings, windows, doorways, chairs and tables were particularly elegant. These were enhanced by the use of trencadis on the outside and full tiles in bright colors on interior walls. Particularly stunning is the stairwell/atrium in blue and white tiles. Throughout the house, both inside and out, there is a wonderful chromatic harmony.

In the process of this residential restoration, Gaudi enlarged the inner courtyard, changed the first floor dramatically, and added two more stories to the building. These added not only height but greater function to the building allowing for useable attic spaces for servants quarters and household functions. This service zone allowed for preparation of laundry and hanging out the wash on the roof. The decorative chimneys on the roof act as both air vents and smokestacks.

Gaudi used a combination of natural forms and geometry to enhance the house. Cleverly working from nature, he used trencadis, the broken tile mosaic, to apply floral motifs with geometric patterning. This adds to the happy even bouyant quality of the space.

In contrast to the dramatic coloration and richness of the rest of the house, the attic areas, upper and lower, were designed to be purely functional by Gaudi. They are painted a pure white. However, far from pure minimalist design as this is Gaudi's work, the attic structure is sculptural with catenary arches repeating and defining the spaces. The catenary arches were built from solid thin Catalan bricks that were plastered over. This was a rapid construction and efficient system.

The use of elegant tile flooring in the attic areas sets off the pure white walls as clearly organic configurations that are shell-like as well as sculpturally skeletal. Gaudi's sculptural sensibility predates Modernist pure white more rigidly rectilinear forms by decades.

Casa Batllo's roof and roof terrace have great personality. The architect let his imagination run wild with colors, textures, forms and materials. This vision transforms a rather mundane aspect of functional architecture into a wonderful sculptural arrangement. Set off against the dragon's back that acts as the edge of the roof, the two stairwells, the four groupings of chimneys and ventilation shafts are enhanced in colorful trencadis that shifts from light to strong tones. It is a roof like no other.

This is a residence of joyful visual poetry where the architect has drafted in spatial, material and colorful stanzas. His muses were nature, mysticism, symbolism and Catholicism with a touch of Catalonian pride. Casa Batllo is a true expression of architectural exuberance and design delight.

Up the street along the Passeig de Gracia is Casa Mila, La Pedrera (The Quarry). This is Gaudi's last residential and secular project completed before focusing entirely upon his obsessive cathedral, La Sagrada Familia. As the story goes, Pere Mila was left a bit awestruck after visiting the renovation of Casa Batllo. Josep Batllo was his father's business partner. Mila decided to commission Antoni Gaudi to build his family's home. The Mila family would live on the main floor (el principal) and apartments were to be rented on the floors above.

In the Fall of 1905, Pere Mila applied for permission to demolish the three story structure that sat on the property that he wanted to build his new residence. In February of 1906, the architectural plans were submitted to the Barcelona City Council for building permits.

A complicated relationship developed between Gaudi and the Mila family. Throughout the design and construction of La Pedrera, there were numerous and often major differences between Gaudi and his clients. The architect went well over budget on several occasions. He also pushed aside City of Barcelona building guidelines to use more than permitted building space restrictions. This led to problems and potential fines from the City Council. The City Council eventually acknowledged the exceptional character of La Pedrera in 1909.

Unhappily, Gaudi and Mila fought over design fees for many years as well. This resulted in a lawsuit before the Barcelona Tribunal Court that eventually ruled in favor of Gaudi in 1915. Therefore, the project was a highly contentious development. Mrs. Mila hated Gaudi's aesthetic but went along with her husband's wishes. When he died, she bought furnishings to her own more traditional formal taste.

The influence of the natural world is particularly evident in Casa Mila. It was popularly name La Pedrera because it resembled a stone quarry. The totally undulating apartment structure combines advanced engineering techniques and Gaudi's personally daring aesthetic sense. The finished project is at once one of the most influential and controversial buildings of the 20th century.

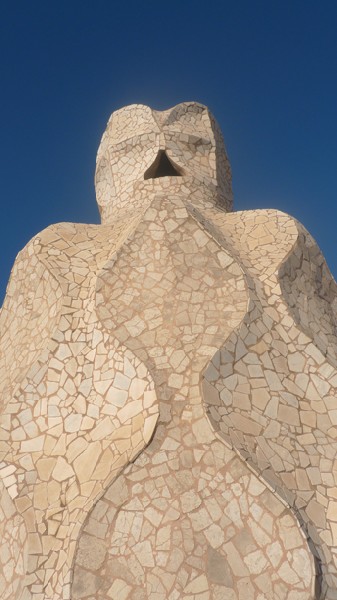

The imposing curvy structure is like a series of stone waves set one upon another with large pieces of metal "seaweed" floating at intervals and serving as fantastic balcony railings. Sun and shadows move across the facade rippling and dancing if on a desert or on the sea or in the mountains. On the roof terrace, the chimneys are giant characters in a mythological narrative and symbolic of Gaudi's referential imagination. Owls and African masks seemed to have been included in the tops of the chimneys.

Not only were the architect's curved forms and shapes ornamental and decorative, but they also were highly functional for a large apartment building. The two large interior atria, referred to as patios, illuminated. Gaudi distributed the rooms positioning the bedrooms and living rooms toward the street and service areas closer to the atria. For these two tall spaces, Gaudi devised an original column and beam structure that allowed the free distribution of space. This method did not have load-bearing walls.

Not surprisingly, Casa Mila's unique boldness of its organic shapes aroused a variety of reactions. Many were not positive. It was a structure that at first seemed not in harmony with the rest of the boulevard and neighborhood, The Eixample. As the center of upper class and the bourgeoisie, wealthy families commissioned their home design to distinguished architects. These more traditionally crafted buildings created a more homogeneous and consistent urban fabric. However, when completed, La Pedrera represented an aesthetic and engineering tear in the city tapestry. Its undulating sculptural appearance made it one of the most striking and controversial Barcelona buildings.

La Pedrera's main entrance leads into a vestibule that has access to apartments. The ground floor was built for businesses and shops. The main floor was the residence of the Mila family. All of the upper floors were and still are rental apartments. The curvilinear shapes are consistent throughout the structure. The waving form balconies are combined with irregular railings that are bristly and thorny plant-like sculptures.

Gaudi conceived the structure as a living organism in constant movement with a structure that was flexible and adaptable. Ahead of its time in many ways, La Pedrera included a garage. Located in the basement, this was one of the first automotive garages in Barcelona. Because of the architect's innovative pillar, column and beam framework that sustained all of the buildings weight, the apartments were all open spaces that allowed for individual room partitioning configurations by each tenant. This open plan predated Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye open plan structure by more than two decades. On the top of the building was a communal space for rooms for laundry and keeping firewood.

The large structure is pretty much monochromatic, slightly colored only by the sun moving across the sky. Except for the patios and other interior spaces, unlike Casa Battlo, there is little color integrated into Casa Mila. Form and function, shadow and light are Gaudi's tools to enhance La Pedrera.

The railings on the building are architectonic sculptural forms. Though based upon vines and other organic shapes, they are extremely abstract. The iron metal pieces act as a decorative punctuation to the flowing stone facades. These pieces were made from recycled scrap, a combination of sheets, bars screws and other found elements. They were produced under the guidance of Gaudi with the collaboration of the younger architect Jujol. These are considered among the world's first abstract sculptures. Like Gaudi's other works, they were revolutionary, transcending traditional craft, converting functional art into abstract forms.

Casa Batllo and Casa Mila are two very different residential structures. Yet, they share much of the same architectural vocabulary. This is the unique, even rather eccentric, visionary vocabulary of Antoni Gaudi. Each building is a visual narrative drafted by a mystical, nature-loving, piously religious artistic genius.