David Hockney's California Dreaming

Subdued Met Retrospective of a Pioneer of Pop

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 31, 2018

David Hockney

Nov. 27 through Feb. 25

Metropolitan Museum of Art

While described as a retrospective in eight galleries with just 60 paintings, 21 portrait drawings and five of his ground-breaking “Joiner” photo collages the David Hockney exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a bit of a tease.

It has been installed by Ian Alteveer, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Met, which collaborated on the exhibition with Tate Britain and the Pompidou Center in Paris. Through February 25 it remains on view in New York.

While regarded as a founder of the 1960s British branch of Pop art there is an unbearable lightness of being that pervades this evocative but oddly benign overview of the work.

Because he refused to write a required essay the Royal College of Art initially refused to grant a diploma. By the time they relented in 1962 he had already emerged in the “swinging” London art world.

Not long after initial success, a sold out debut show, he moved to Los Angeles in 1964. The artist returned to London in 1968, and from 1973 to 1975 lived in Paris. In 1974 he began a decade-long relationship with Gregory Evans who moved with him to the US in 1976 and as of 2017 remains a business partner. In 1978 he rented the canyon house in which he lived when he moved to Los Angeles. He later bought and expanded it to include his studio. He also owned a beach house on Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu, which he sold in 1999. Today he divides time between LA and Kensington in London.

The first gallery of the exhibition reveals the influence of Francis Bacon and abstract expressionism. The derivative juvenilia is strikingly different from the cool, colorful, slick paintings he developed in California. The early works are notable for their sexuality which at that time was more unique and courageous than it is today.

The understated, refined eroticism that pervades decades of the work, from a current perspective, appears more benign and less vulnerable than it was initially. The imagery and context is explicit but less than shocking in We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961). Its title derives from a poem by Walt Whitman. From 1963 consider Domestic Scene, Los Angeles in which, while showering together, one man washes the back of his partner. Today, that hardly elevates an eyebrow but gay sex was still a crime in Great Britain.

It was decriminalized between men older than 21 in 1967. But it remained illegal to have sex in a hotel or with a third party. The Stonewall Riots began on Christopher Street in New York in June, 1969.

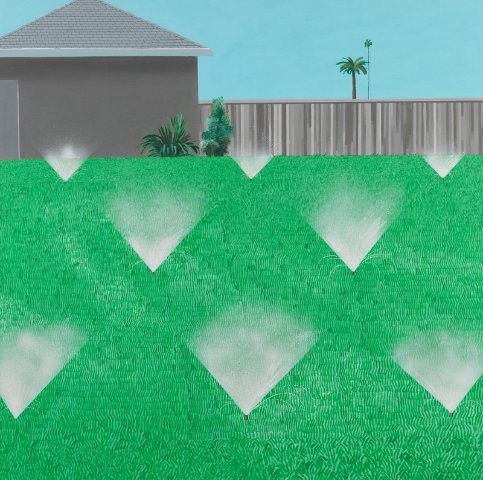

Working in California, then a provincial outpost of the global art world, allowed the artist to develop his own style. While loosely identified by the pop art movement his work is more tangential to what was created simultaneously in New York and London.

The less ironic and low key narrative of the California works are more oblique than specific. He was always a keen and clever scavenger of periods of art history. During a casual cruise through the exhibition, the pace and intensity of most visitors, blink twice and you will miss the originality and gentle subversion of the work.

Like the surfs up music of the 1960s Beach Boys much of his work in the California genre is just fun, fun, fun till Daddy takes the T-Bird away.

It lacks the gravitas or intellect that we associate with major masters. He slips under the radar compared to Rauschenberg’s outrageous energy and invention, Warhol’s droll wit, or the sly intellect of Johns.

The better notion is that Hockey’s oeuvre is more different, off the mainstream, than directly equivalent or comparable to the major players.

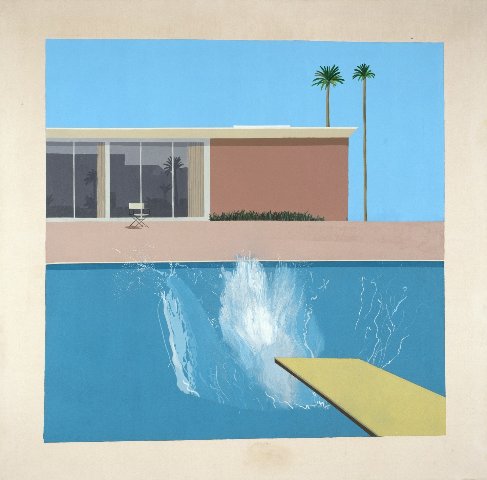

The zeitgeist of a culture where it never rains is always temperate, and back yard pools are ubiquitous is a bit difficult to take seriously. His paintings accordingly are bright, pretty, and gay but have the gravitas of green jello.

Or so it might seem. Like the rococo there is a lot of work to make them so bright, light, decorative and apparently frivolous.

His “The Room, Tarzana,” an erotic painting from 1967, makes me think of the delicious paintings by Boucher the favorite of Madame de Pompadour. There is a similar pose of the model depicted face down on a bed with buttocks exposed. Compare the rococo “Portrait of Marie-Louis O’Murphy” by Francois Boucher, 1752 to Hockney’s supine lover.

As Titian said “Oil paint was invented in order to paint flesh.” That aptly describes the work by Boucher, one of my favorite paintings, although Hockney created his with acrylics.

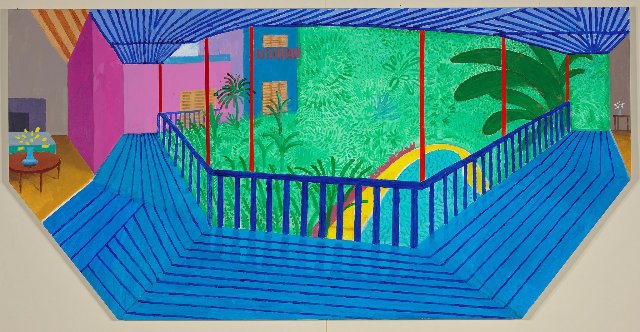

The use of the then relatively new medium allows for flat, saturated expanses of color and subtle, barely discernable levels of chiaroscuro. At the time acrylic was most notable for being watered down in stain and color field paintings. Hockney created a flatness and shallowness of field oddly in sync with the pronouncements of Clement Greenberg who regarded figuration as reactionary.

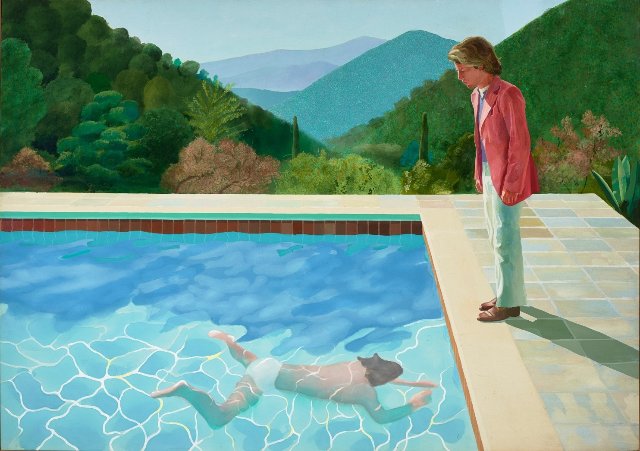

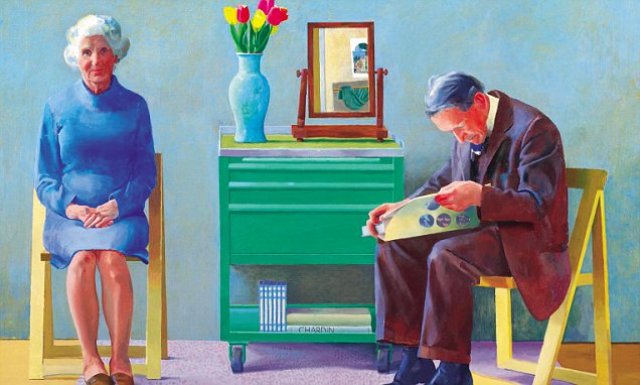

That cool, crisp, low relief is a signifying aspect of a brilliant room of large scale portraits. They entail couples- Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy; Ossie Clark and his wife, Celia Birtwell; and Henry Geldzahler, founding curator of the Met’s department of 20th-century arts, with Christopher Scott- as well as off setting other elements like a white cat, arrangement of tulips, or objects of modern art.

The settings, interiors and terraces of the subjects, as signifiers of wealth and power, are as important to the portraits as the features of the sitters. It is amusing that the rotund Geldzahler is not only at home with modern furniture, but bears an uncanny resemblance to it.

The most revealing portrait, on a more intimate scale, depicts his parents. In a manner that evokes pride and approval she stares out at us. His father is seen in profile, bent over, buried in a newspaper. She appears in other works including a well know photo collage of her sitting in a church yard in the rain. He created a number of photo studies of her not seen in this exhibition.

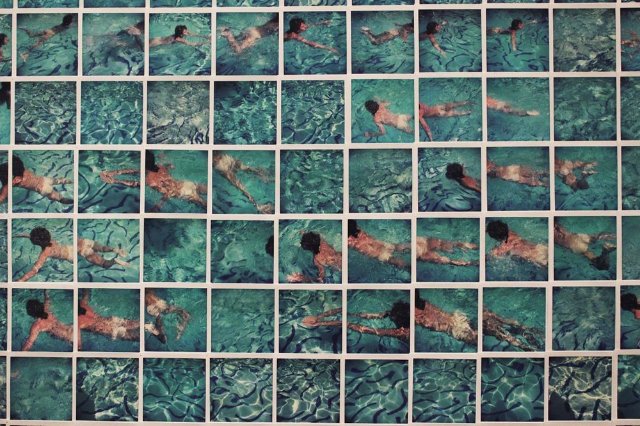

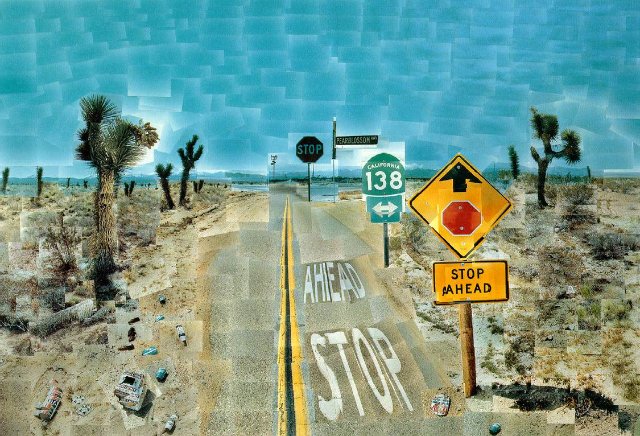

In a Times review Roberta Smith, who should know better wrote “Five of his gimmicky if implicitly Cubist photographic collages beginning around 1982 signal his release from the confines of one-point perspective.”

She’s right about Cubism but dead wrong that his explorations of photography and the resultant “joiners” were anything but “gimmicky.” In a “Come in here Watson I need you” moment he stumbled on the single point frozen moment captured in a photograph. By shooting a subject in a burst of slightly altered positions and moments he was able to paste them together to create a multi-valent study. Initially, he formed grids of Polaroid images and then moved on to shooting multiple rolls of commercially processed color prints. Following the lines and vectors of his shots created interesting fragments.

It was the product of the photographer as Cyclops. Smashing together ever more complex elements meant evolving from more simple analytic cubism to the dynamic motion of futurism. He was breaking down and reinventing the space/ time continuum of the uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics.

That culminated in the masterpiece "Pearl Blossom Highway." That iconic collage, after which he abandoned the experiment, is included in the exhibition. It is compressed within the rectangle in the manner of a painting. The seemingly clear blue sky is a dense mosaic of cut and pasted tesserae.

Moving into the next galleries of landscape panoramas from the Grand Canyon to rural England, or the terrace of his California home, it is evident what he learned from the multiple perspectives of his collages. Now in a more controlled manner we see the “Joiners” as the individual panels that create composite, large format paintings.

The late works are richer in color, more fluid, looser and painterly. It reflects the security of a firm reputation with nothing to prove. With intoxicating exuberance the artist appears to enjoy and please himself. Me too.