The Enigma of Sarah Caldwell

Two Biographies Try to Unravel Her Mystery

By: Larry Murray - Feb 06, 2009

Challenges: A Memoir of My Life in Opera, by Sarah Caldwell with Rebecca Matlock (Wesleyan University Press, 2008)

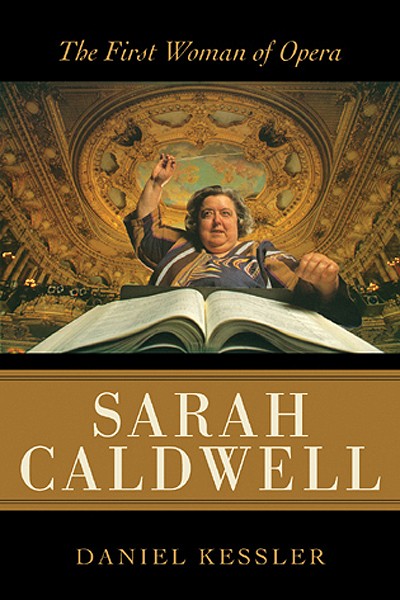

Sarah Caldwell: The First Woman of Opera, by Daniel Kessler (Scarecrow Press, 2008)

SARAH CALDWELL

Often hailed as the first lady of opera for her innovative productions, Sarah Caldwell staged and conducted some 100 operas, ranging from baroque to avant-garde in her more than 30 active years in Boston. She broke the glass ceiling at New York City's Metropolitan Opera becoming its first woman conductor in 1976. Born March 6, 1924 in Maryville, Missouri, she died in Portland, Maine on March 23, 2006 at the age of 82. Whether you loved or hated her, she was an unforgettable master of great opera. Her productions more often than not seared themselves into our memory.

For some, that memory might have been the moment Beverly Sills descended from the rafters as Queen of the Night in Mozart's The Magic Flute. For others it might have been the breathtaking bel canto duets of Joan Sutherland and Marilyn Horn in I Puritani or Semiramide. Nobody who saw the work of this impresario can deny she was a gifted craftsman, if not an absolute genius, at staging opera. In her prime, in the late sixties and early seventies, music critics from around the nation would make the trek to Boston to see her work first as the Boston Opera Group, and later as the Opera Company of Boston.

However, not all she did was truly original. Much of her innovative material was a further iteration of the work of Walter Felsenstein at East Berlin's Komische Oper. She also employed talented unknowns from behind the Iron Curtain, such as the Czech Josef Svoboda. Shortly after his work on Intolleranza at the Back Bay Theatre, the two talked all night about his defecting to this country. The next day he did just that. Svoboda, who liked to call himself a scenographer, went on to design more than 700 productions around the world. He was the first designer in America to use lasers and seamless projections in combination with live action.

The two biographies which have appeared since her demise have documented the operas, casts, and details of her artistic output. In her memoirs, edited by Rebecca Matlock, Caldwell wrote out and dictated much of the material, with her editor adding personal observations and history. This resulted in a seriously flawed history in which Sarah Caldwell, the person, is largely obscured by the myth she liked to create about herself. We do not find much about her personal life, about her interest in things beyond opera and music, and how she grew to be both literally and figuratively larger than life. Those aspects are better found in Daniel Kessler's book.

Sarah's memoirs use her very selective memory to excise problems and failures, and to settle grudges. Whole boards of directors, rafts of major donors, artists and musicians are completely ignored. The former Massachusetts Senator Edward W. Brooke, President of the Board for many years, is nowhere to be found in her book, nor is John G.L. Cabot who opened the purses of notoriously stingy Boston Brahmins to Sarah's use. Also ignored is one of her most valuable allies, Harry Shapiro, the BSO french horn player who recruited and assembled her pit musicians. Among her omissions is Henry Guettel - theatrical royalty no less! - who managed her first major touring company under Sol Hurok and cleaned up many a mess she made.

About the only good things that came from Sarah's legendary peculiarities were the stories that those of us who worked with her could share with each other. It became a sort of game of one-upmanship that provided common ground when I first met and actually worked with the genial Harry Shapiro at the BSO and Boston Ballet, and with Henry Geuttel at the Theatre Development Fund. Sarah sure knew how to pick talent, even though she could also abuse it. The great scenic designers Helen Pond and Herbert Senn stuck with her through thick and thin. When E. Virginia Willliams, founder of the Boston Ballet, asked me to recommend a set designer for The Nutcracker, their work came to mind. To this day I think they designed and built the most glorious sets the Boston Ballet has ever owned.

Beverly Sills sang with Sarah many times, and it is my theory that she got her nickname "Bubbles" as a result of her Boston engagements. Sills would often attend the legendary post-performance champagne parties of Sarah's donors at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. Liz Donahue was famous for hiding a case of freshly chilled champagne under her table as "last call" was announced. Liz single-handedly kept the party going well into the wee hours. Sills was only one of many who knew which table to visit when glasses were emptied. Opera singers like their bubbles.

That Sarah bounced checks like a con artist is legendary. "Bubbles" even got one. When checks were issued, everyone would race to the bank to cash or deposit them before the Opera Company's account ran dry. Of course, details like this are nowhere to be found in Sarah's memoirs. As a serious writer on opera, Kessler does not dwell on this aspect of Caldwell, but offers enough important detail to gain a fuller sense of how she approached the business end of making operas.

Kessler received only minimal participation by Caldwell in his book, so he talked to many of the artists and managers who worked with her. He was no stranger to either Caldwell or her productions - he spent many years following her career and seeing her work. As a result, his book provides the more satisfying look at Caldwell as an artist. He also provides some colorful insights you are not likely to read elsewhere.

He writes: ""When conducting, she often wore long black dresses, frequently hiding tennis shoes or comfortable moccasins. At the time the guest-conductor invitations began pouring in, Sarah's weight was nearly three hundred pounds - distributed over a five-foot-three-inch frame. The excess did not permit her to stand for any extended length of time, and so in her appearances with various orchestras, Sarah usually elected to sit high at the podium, behind a stockade-like enclosure. This device prevented the audience from focusing on Sarah's large rump instead of concentrating on the performance itself. However, the enclosure was of no value to the orchestral players, who were not spared a most unfortunate view - Sarah tended not to wear underpants."

In the sixties and seventies the eccentric Caldwell was seen as a genius. She was the first woman to conduct at the Met. She was promoted by Edgar Vincent, her publicist, as the breakthrough woman conductor - the Age of Feminism had reached classical music. Offers to conduct came from around the world, and Caldwell traveled the globe, but neglected her opera company at home. Soon the novelty of a woman conductor wore off, fame faded, and her artistic muse suffered. She went from being a groundbreaking artist to an overweight and undisciplined oddball.

After her "Making Music Together" cultural exchange program with Russia left stacks of bills unpaid, Secretary of State George P. Shultz had to intervene to prevent it from becoming an international embarrassment. She struggled on for another two years, but soon her Boston performances ceased. Her constant failure to stick to a budget, or keep her word to ticket buyers, had poisoned the well forever.

There was a final attempt to resuscitate the company undertaken by Caldwell, and a new board (her third or fourth as I recall) headed by Bob Canon, formerly of the NEA. It failed when Caldwell would not work with the board, nor accept its authority.

Kessler tells this story: "During the turmoil of the last days of her company, a former board member recalled stopping by the theater on Washington Street [in Boston] to personally tender her resignation. Sarah was seated behind her desk inside her sanctum sanctorum ready to devour a pile of glazed jelly doughnuts."

Of course, in her memoirs, neither Bob Canon nor this board is even acknowledged. She only refers to him indirectly in passing, and he was her last hope. Following his engagement as company manager, against her wishes, it was inevitable that the new board would quit en masse. It did, and then tried to start up an entirely new opera company. That effort failed as well.

One of the stranger of Caldwell's habits was that she would sometimes close her eyes when speaking to you. Various explanations are proffered by the biographers to explain this peculiar habit. Matlock puts it down to mini-napping. Kessler thinks perhaps it was mild narcolepsy. But as one of those people who seemed to provoke the closed-eye response from Sarah in later years, there may be another explanation.

If Caldwell did not like you, or if she was embarrassed to be in your presence, she simply closed her eyes and ignored you, and whatever emotions you aroused. The last time I saw Sarah it was at a meeting with Bruce Rossley, then Boston's Arts and Humanities Commissioner. There was an attempt underway to restore the Opera House. She had a mortgage on it and Rossley wanted to have Clear Channel buy it, renovate it, and then lease it back to her for several months a year for opera. The Midtown Cultural District Task Force - which I chaired at the time - was trying to help broker the deal which hinged on expanding the shallow stage area. Sarah would open her eyes to speak to Rossley, but neither to me nor to the representatives from her neighbors at Tremont on the Common, who were questioning the expansion of the stage housing towards their building. Sadly, this and other habits did not endear her to others. Tremont on the Common fought the expansion tooth and nail for years.

After Boston, she reigned for a time at the Wolf Trap Festival outside of Washington, D.C. Accounts of her Wolf Trap engagement differ in the two books, and in the memoirs she parses her words in telling about the experience, while in Kessler's account the truth is plainly detailed.

Sarah writes: "The Wolf Trap administration fought constantly with the National Park Service, which was in charge of the theatrical facility. One night there was a terrible storm. It was the night of one of the Aida performances. The cast was on the stage, and the chorus was on the stage, when the highway department canceled because of what they were afraid might happen to the traffic in the storm."

"Our contract stated that if the cast was dressed and on the stage, and a performance was canceled, we would still get paid. that huge Aida cast was not paid. We got sued, not Wolf Trap, by the unions. Somehow we managed to pay, but we were never reimbursed, not even for the orchestra, which was in the pit ready to begin."

In the Kessler book, we find a different version of what happened: "Losses incurred by visiting performing entities at Wolf Trap were not reimbursable, according to the contract, and Sarah's role as music director was of little help, functioning more or less as a traffic cop in the selection and scheduling of events.

"Eventually reimbursement came by way of a court settlement, with the insurance company picking up the tab. Unfortunately Sarah was put in the awkward position of having to sue her employer in order to access relief through Wolf Trap's multi-peril insurance policy."

In the end, Caldwell had amassed three dozen honorary degrees, the National Medal of Honor from Bill Clinton, and $8.5 million in unpaid bills. No notebooks, no plans or schematics, little for the historians to peruse. Most of what she created she did on the fly, out of her head. It came and it went.

These two books will be the primary record of Caldwell's life in the arts. She leaves behind little in the way of audio or video recordings. This is partly due to the ephemeral nature of live concerts and performances, and also to the extraordinary cost of paying the many unions their high fees for the right to preserve them for posterity.

What is available is a video of the New York City Opera production of The Barber of Seville, which she conducts but it is not really her own production, as well as CD's of Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini and Bellini: Capuleti e Montecchi. Some older LP's of Donizetti's Don Pasquale are also kicking around, plus some of the classical music done with the Ekaterinburg Philharmonic Orchestra.

What opera lover would not pay dearly for the ability to relive her many other wonderful productions, from Boris Godunov to Tosca.

In the final irony of her life, both books on Caldwell have the same basic design and photograph of her, and similar chronologies of her productions. Caldwell's memoirs were published several months after the biographical account by Kessler. Coincidence? If only the dead could talk.