Berkshire Museum is For the Birds

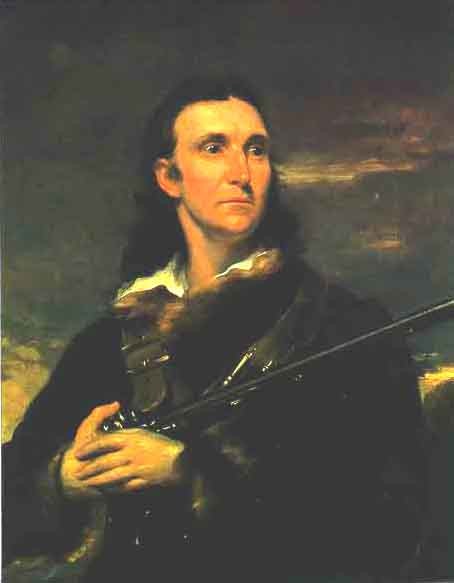

John James Audubon and Morgan Bulkeley

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 12, 2012

There are too few museums quite like the eclectic Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield. It has a parallel interest in the natural sciences and fine arts.

The current tandem of exhibitions Taking Flight: Audubon and the World of Birds, (January 12 to June 17) and Morgan Bulkeley Bird Story (January 24 through March 4) provides vivid testimony of how the museum manages neatly to conflate these seemingly disparate interests and mandates.

While there are several world class fine arts museums in the Berkshires none compare to the Berkshire Museum as a family and educational destination. Little wonder that during Holidays and school vacations the galleries are mobbed with delighted children and their similarly bemused parents.

Another unique approach of the museum is to focus special exhibitions around aspects of a vast and diverse collection of objects and natural history specimens.

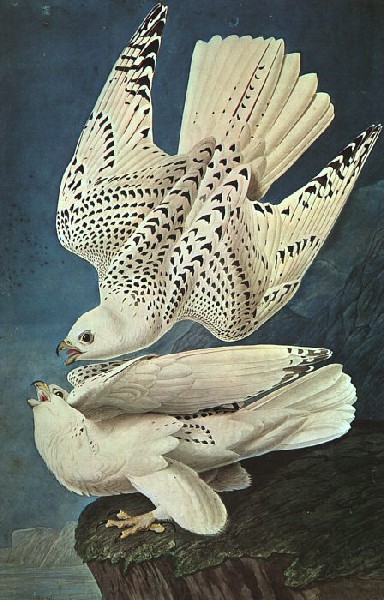

Surely we have seen Audubon prints lots of times but never quite like this. The exhibition centers on John James Audubon and his passion for birds, which drove him to create The Birds of America, a seminal work of science and art that launched his reputation as the world’s most renowned wildlife artist.

More than thirty, original, hand-colored, life-size prints of birds from The Birds of America, engraved by Robert Havell Sr. and Robert Havell Jr. are on loan from the Shelburne Museum, National Audubon Society, Arader Galleries, the Chapin Library at Williams College, and individual lenders. The prints, paired with almost as many bird specimens from the Museum’s collection, as well as loans from Harvard University, comprise the centerpiece of the exhibition. Rare Audubon watercolors and works by Audubon’s contemporaries, such as Alexander Wilson, are also on view.

Before the invention of photography and fast film it was necessary for Audubon to first shoot all those magnificent birds and animals before he could render them with such meticulous detail.

The museum makes that abundantly clear by combining his exquisite lithographs with many examples of stuffed specimens; including a rather imposing ostrich. During the 19th century, when the dictates of fashion were not the object of scorn of animal rights groups, exotic birds were used to create women’s hats, purses, muffs and accessories.

There are a number of vintage fashion accesories on view in vitrines.

As my hipster friend Al the Arab once quipped "A frail will plop a dead bird on her head and call it a hat."

During the colonial era of North America the pervasive trapping of beavers was necessary to feed the fad for fancy men’s tall hats. It was a thriving frontier industry.

It is indeed quite shocking to see the fashion accessories that the museum displays. How could we have been so callous? I recall how thrilled my Mom was when she finally owned a mink coat. Pity the poor minks we might say today.

Actually, you wonder what toddlers will make of all those stuffed dead critters. How will Mommies explain? Perhaps we might return during one of those crowded vacation days and listen in on conversations.

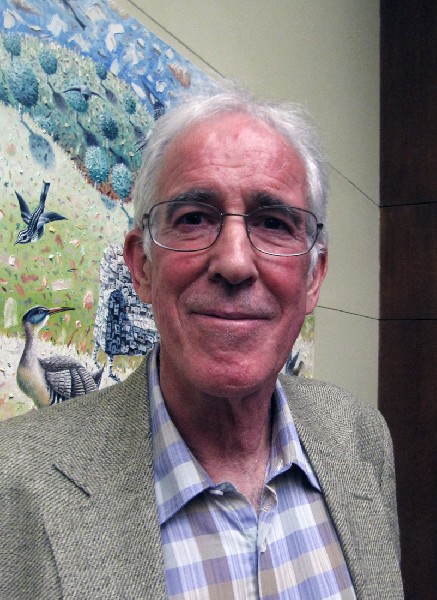

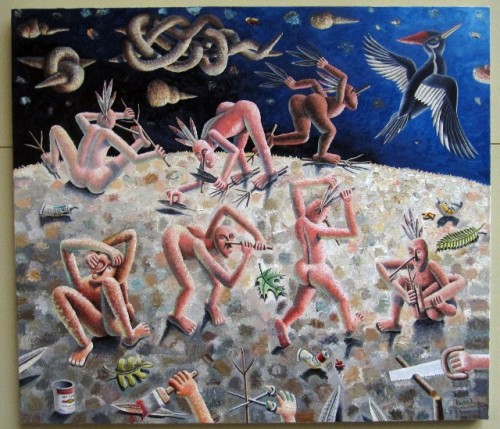

The exhibition of contemporary narrative, fantasy paintings by Bulkeley in the spacious and sumptuous Ellen Crane Memorial Room is a brilliant complement to the Audubon show.

The artist was born in the Berkshire hamlet of Mt. Washington, in 1944, the son of naturalist parents. He grew up with all manner of caged animals which they were researching. After a number of years of living in Cambridge he and his wife settled in the Berkshires in 1985.

At Yale, Class of 1966, he majored in literature so it is not surprising that his work has a bias for narrative.

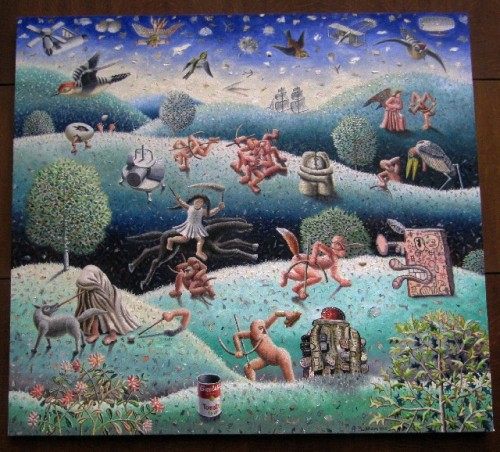

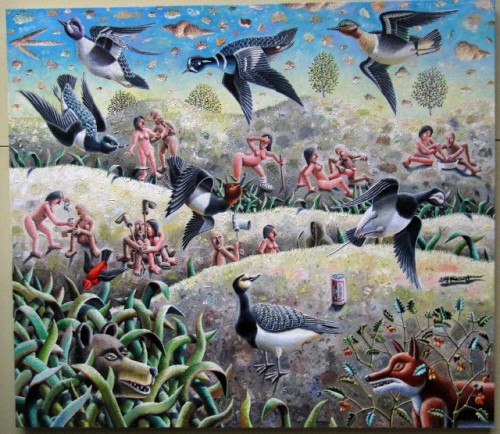

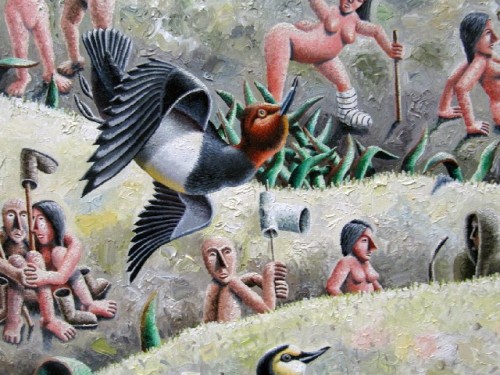

The large canvases, which take several weeks to complete, are both reductive, primitive, cartoonish as well as galvanic and sophisticated. The landscape is rendered with rolling hills, gum drop trees and shrubs that evoke the stylizations of the American Scene master Grant Wood. In the manner of applying paint with short impasto strokes Bukeley draws on the approach of late Monet and Seurat but with more surface texture. His palette favors soft, mid chroma tonalities.

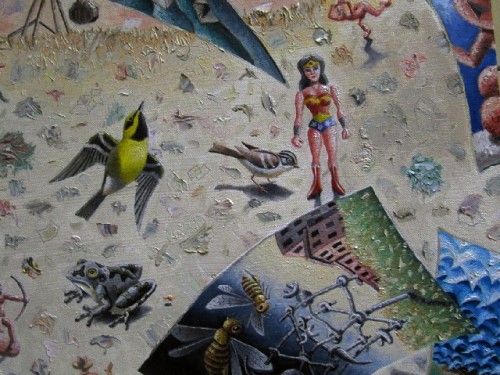

Typically, the generic landscapes are populated by a plethora of objects and signifiers. These trigger the interests of the artist from icons of the fine arts, like a Campbell’s soup can channeling Warhol, to snippets and quotes from art history spanning from Fra Angelico to Rousseau, Guston and Serra.

When Bulkeley needs a statuette of Wonder Woman or the Statue of Liberty, as he explained during a well attended artist’s talk, he often borrows the objects from his artist friend Jarvis Rockwell a compulsive collector of toy figurines.

The artist has created a dense and complex iconography. It is so eccentric and specific to his persona, however, that it would take a shrink to figure it out. It reminded me of gazing long and hard at Garden of Earthly Delights a tryptych by Hieronymus Bosch in Spain's Prado Museum.

While the objects and icons are rendered in miniature on a larger scale are oddly rendered naked humans and highly detailed depictions of birds. Aha! The Audubon connection.

It is interesting to consider that the humans, with ritualistic postures and set in vignettes of arcane ceremonies are all naked. No genitals it seems in this PG rated exhibition. Actually, come to think of it, the birds are also “naked” but we tend to think of them as “dressed” with their feathered finery.

In Morgan's world the birds and animals come off better than humans. As the paintings state we clutter nature with our trash and stuff. Here such things as sheets of newspaper with cartoons, photos of famous men from Einstein to Freud, and the litter of magazines.

As Bulkeley commented in his talk getting rid of all our waste and trash is a major concern for the every expanding human race. He commented with alarm about an island of trash in the Pacific as large as the state of Texas.

Man or homo sapiens, significantly, is the only mammal that fouls its own nest. Even pigs, it seems, are more discreet.

Good grief.