The Esplanade Vision Unveiled

Vision To Make Esplanade Best Park in The World

By: Mark Favermann - Feb 13, 2012

Almost every American knows about the Esplanade. Each year, it is where the Boston Pops celebrates July 4th by playing Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture with a background of majestic fireworks over the banks of the Charles River. For this event, between 500,000 and a million people crowd the Boston park, and scores of millions watch it on television. An additional 2 million others "use" the Esplanade every year.

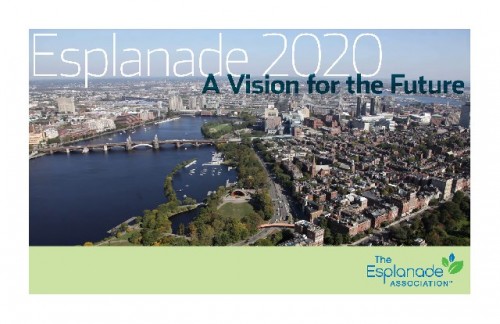

On February 9, 2012 before a standing room crowd of over 350 interested citizens, state and city officials and professional designers, the Esplanade Vision 2020 was unveiled at the main branch of the Boston Public Library.

The presentation started with a beautifully illustrated 20 minute voiceover slide show narrated by Will Lyman, PBS Frontline's voice of gravitas as well as the voice explaining the world's most interesting man commercial.

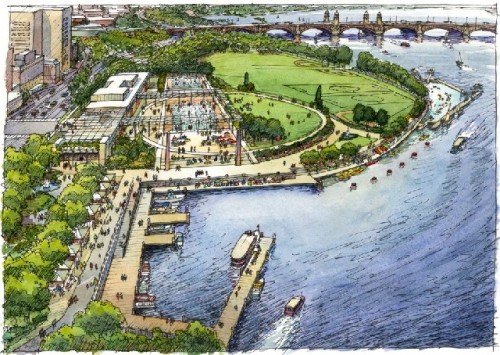

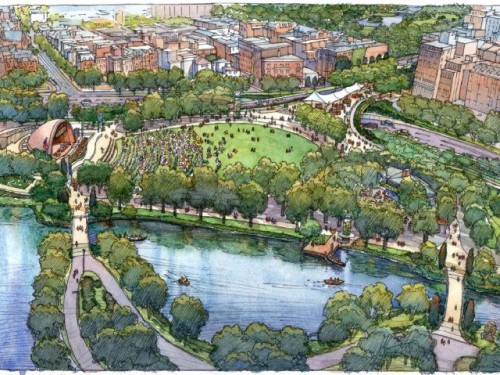

Aerial photographs were by master photographer Peter Vanderwarker. Renderings were water colors created by the gifted and award-winning Frank Costantino. The study and plan took 25 months of intensive discussions, design strategies, institutional and government outreach, documentation, renderings and review.

Sponsored by The Esplanade Association (TEA), a nonprofit "friends" of the park organization, the Esplanade 2020 project, was to be a park visioning study for the next 10, 20, 50 or even 100 years of the linear waterside park.

Along with state officials from the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, sometimes twenty-five to thirty-five prominent and emerging architects, landscape architects, engineers, urban designers and planners took part in the meetings. At any one time, there were a lot of opinions and creative ideas in the room.

Luckily with all the high powered designers and engineers at each meeting, egos were mostly kept in check with everyone's eye on the prize of making the Esplanade what it should become: One of the world's greatest open space parks.

I got an email early in Januaray, 2009 from a friend and colleague Jane Howard, the head of Howard-Stein/Hudson, a busy firm of transportation engineers and planners. She said that the Esplanade project needed me. I called her, and she explained that my skills as an urban designer who used design tools to create the notion of a sense of place would fit precisely with what the project wanted to achieve.

With a little thought, it appeared to me that this pro bono effort would be a once in every couple of generations opportunity. The last serious design thought given to the Esplanade was in the 1950s. This was not to be a missed opportunity.

Not shy, at my first meeting, I spoke up (sometimes rather loudly), and continued to communicate thoughts and concepts throughout the project. Soon I got deeply involved in the process.

Project leaders included project manager architect/urban designer John Shields (formerly of Icon Architects), architect/urban designer John Stebbins (Partner Emeritus at Cambridge 7 Associates) and architect/developer Anthony Pangaro (senior partner in Millennium Partners who are rebuilding the Filene's site among other downtown Boston projects). Landscape architect Craig Halvorson (Halvorson Design) began the project with us, dropped out for a while, and rejoined before the unveiling.

Tasks were divided. Shields worked on the overall scheme in an urban design sense. Stebbins looked at specific structures and activities. Pangaro focused on transportation issues and circulation. My work was on a sense of place, gateways (sense of arrival), signage/wayfinding, public art, lighting and park amenities.

All during the design and planning process there were scores of other talented professionals who also took part. Transportation engineers, landscape architects, planners, graphic designers, urban designers and various community stakeholders all flowed in and out of the almost weekly meetings. Each participated as they best and often brilliantly could.

A couple of individuals brought thoughtful analysis to the traffic planning and engineering issues. David Black of VHB and Ken Kerchmeyer were invaluable in their insights. TEA staff project manager Jessica Pederson and TEA executive director Sylvia Salas brought energy and often organization reasonableness to the process.

As more and more background information, prescient images and visionary sketches emerged, there was an abundance of small as well as sometimes medium sized and even large public meetings during the two year process.

Every meeting or project piece was not always a day at the beach. Disagreements raged at times. Strategies were debated. Political and aesthetic approaches constantly were wrestled with. However, most rough edges were smoothed over. Hurt feelings often lasted only a few minutes, a few days, or a few weeks! Design is a human as well as aesthetic process. Thoughtful concensus was generally achieved. This was a historic process about the future betterment of an equally historic project integral to the quality of life of Metropolitan Boston.

At my studio, Emmett Burson and I wrestled with completing the final report over several weeks that stretched to months with revisions, refinements and editing. This was not a simple task. It would not be an understatement that some days we wanted to pull our hair out. Near the end of the process, graphic designer/art director Steve Wolf added his eye and skill to the document to finalize it. Meanwhile John Shields went through scores of iterations to finalize the voiceover slideshow.

The Esplanade is as American as apple pie, the stars and stripes, and motherhood. It is literally America's home of the 4th of July! Additionally, people visit the waterside park each year to walk, sail, stroll , exercise, bike, skate, to just sit or sunbathe. So the interest in the project was generally very positive. However, there was a bit of skepticism as to how was it going to be funded. This is especially noted in our time of greatly diminished public resources.

But sort of like the mythic Field of Dreams, if you design it right, it might eventually be built.

The high level volunteer design and engineering professionals and staff worked in collaboration with the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the state agencty that stewards the park to recommend and prioritize park improvements. The DCR runs the state park system (urban and suburban) along with forest conservation areas. Mount Greylock Glen, the tallest mountain in Massachusetts is one of its parks.

The overall goal of Esplanade 2020 is “To forge a shared vision for the park’s future—one rooted in its nineteenth century origins, but looking forward to address the needs of the broad contemporary public.” This lofty ideal was continually strived for during the two year process.

The Charles River Esplanade ranks among the Commonwealth’s greatest assets. It lies at the center of a network of parks planned by pioneering landscape architect and theorist Charles Eliot in the 1890s. He referred to the Esplanade as the system’s “crown jewel.”

More than a century later, however, the jewel has lost its luster a bit.

So the Esplanade needs considerable revitalization and long-term care. Our Vision is to induce and attract creative public/private participation in reviving and enhancing its glory.

The Esplanade opened in 1910. Interestingly, the same architect who initially designed and built the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was the Esplanade's design director, Guy Lowell.

A lack of resources in recent decades, repeatedly deferred maintenance, and extraordinary popularity (an estimated 3 million annual visitors, reaching a typical daily peak of 20,000 in summer) have degraded the park’s paths, landscape, and beautiful original structures. The Esplanade has been literally “loved to death.” Although several studies have identified some of the park’s biggest problems, a broad vision for its future has not emerged until now.

Something of a red herring was floated or spun as an aspect of the vision; a tall ferris wheel to be set where the deteriorating Science Museum garage is. Think London Eye. It would be a revenue generator for the museum. Parking could be nearby at other locations. The entrance to the museum would not be through a parking facility.

The idea is that a blocky parking lot that is leased at a uncommercial rate to the museum by the state (a deal made in a previous Massachusetts political paradise--wink, wink, nudge, nudge) should not block wonderful views of the Charles River, the park and city skyline.

Many of the press picked up on this notion as a major point of the vision. Controversial-yes. Provocative-yes. Major--not necessarily. But a way to rethink what was there. Perhaps another idea would be better. The Museum of Science is upset about losing its parking facility, but should a monolithic brick structure take up so much of what should actually be public park space?

The Lock and Dam location is where the Esplanade physically begins. This land bridge between Cambridge and Boston was never supposed to be the location of large structures. Currently, the Science Museum, its ungainly parking garage, a police facility, and state bureaucratic parking areas take up the space.

The Esplanade Vision suggests that this area be redesigned and allow for a merger of science and horticulture exploration. It recommends education with greenhouses and exhibits that connect the science and green education with the physicality of the Esplanade.

Moving West up the Charles River, the vision evokes a concentrated physical recreation area that has boating, sports and even swimming. The formerly polluted Charles is now rated B+ in water quality, a designation that allows swimming. The vision calls for the over a decade long neglected Lee Pool will be reopened for recreation and exercise as well.

At the Longfellow Bridge (about to go into elaborate rennovation), a new much more accessible Esplanade entrance is recommended. This will be based upon a new configuration of Storrow Drive that will give back parkland taken away by overly aggressive roadwork in the early 1950s.

By the way, the generous Brahmin Storrow family gave $1 million in 1931 for the enhancement of what was then referred to as "The Embankment." This number would be over $100 million now. The only codicile by Mrs. Storrow was that there should be no major roadway through the park. However, only five years after her death in 1951, named after her husband Storrow Drive was completed separating the park from the City of Boston. She has probably been spinning in her grave ever since.

Esplanade Vision 2020 wants to retake usurped land from Storrow Drive, much of it is in the form of too long entrances and exits from the roadway. The great design notion is to recreate Storrow Drive as a true parkway rather than a speedy highway. Eventually, east and west bound traffic can go on to the Mass Pike that will be free and have additional exits (perhaps one at Kenmore Square).

Making roadway improvements can be accomplished cost-effectively as tunnels and roads come up for scheduled refurbishment and restoration. Strategtic planning and political will need to be joined to reach design objectives. This is particularly true of traffic mitigation and parkway enhancement.

Of course other big ideas include major restoration and upgrading to the plantings and trees, restoration of crumbling structures and additional services including bathroom facilities, restaurants and cafes. Park pathways will also be divided between fast moving bicyclers and skaters and walkers and strollers.

Public art is envisioned to be spread over the Esplanade sillouetted by the Charles River. Seasonal art festivals would fit nicely with the various concerts scheduled during summer months. Better and accessible entrances are prescribed for Arlington Street and Dartmouth Street. Better use of the waterfront is conceptualized for the area now called the BU Beach near Boston University.

Perhaps one day, Harvard University will pay for a bikeway from Harvard along the Esplanade? Just a nice thought.

Taking down the clumsy Bowker Overpass near Kenmore Square will allow the Esplanade to connect parkland to the neglected Muddy River's section of Frederick Law Olmstead's Emerald Necklace.

Many aesthetically conceived amenities--benches, pavilions, water fountains, lighting and easier wayfinding are recommended in the vision. Wayfinding should be extended beyond the park directing first time visitors to it from Boston, Cambridge and Brookline. Right now you can't get there from here.

The Esplanade Vision 2020 was a labor of love for a great park and a piece of our urban heritage. All involved feel a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. But this was only the first step. In our time of limited resources, we have to be most creative in trying to harness public and private support.

As it is, the Esplanade is one of the most elegant open spaces in an urban setting anywhere. As the photographs that accompany this article demonstrate, it is magnificent from 2000 feet up. But on the ground and at the water's edge, it needs great and continued upgrading and care. Successful for its first 100 years, it will be even more beneficial, vibrant and beautiful in its next century if the Esplanade Vision 2020 is followed. It could become one of the best parks in the world.

Note: a copy of the Esplanade Vision 2020 Report can be downloaded at http://www.esplanadeassociation.org/projects/TheEsplanadeAssociationProjects-Esplanade2020VisionStudy.html