Hannah Höch at London's Whitechapel Gallery

Pioneer Dadaist of 1920s Berlin

By: Whitechapel - Feb 13, 2014

Hannah Höch was a pioneer Dadaist of 1920′s Berlin. Somewhat forgotten, or at least pigeon-holed by art history; she was a social provocateur who clashed with the Nazis and was found guilty of Entartete Kunst (degenerate art).

The exhibition at London's Whitechapel Gallery is a survey of the artist’s works on paper through March 23. It is the first major exhibition of Höch’s art in Great Britain, bringing together over 100 works from major international collections. The exhibition examines Höch’s career from the 1910′s to the 1970′s—if circumnavigating her prolific array of oil painting and drawing—the exhibition at least focuses on her most remembered output: photo-montage and collage and her works of fantastische kunst.

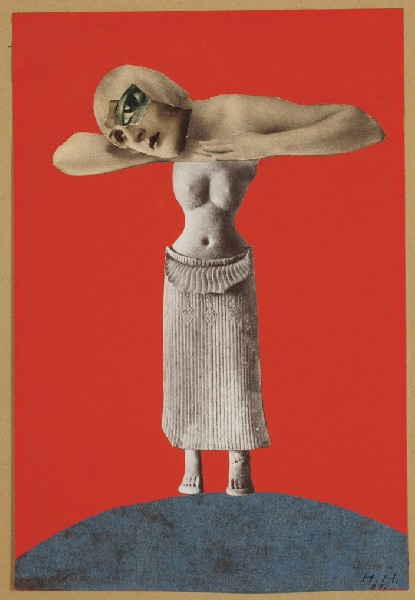

Höch’s art was often an astute social satire on the female form, and the politics of Europe. The artist’s human condition is resolutely female, and reflects her own experiences. A reflection of the female form, and identity in society, as well as art.

These were figurative abstractions of tension and urgency. A juxtaposition of formal abstract aesthetics and emotional socio-cultural clout—initially reflecting a period of enthusiasm and great change in a post First World War Berlin.

Yet Höch’s art was radical in contrast to the purely formal concerns of the Dadaist movement. The ‘simultaneous muddle of noises’ that the Dada Manifesto called for was discarded by Höch for a certain aesthetic balance, a definite composition, and a narrative structure, often politicized.

This one-woman Dadaist revolution also reflected a more obvious socio-political content and feminist drive, prevalent in the creative party of 1920′s Berlin, eventually to be trampled under booted heel by a ‘mad, inhuman, bestial clique‘—as the artist herself described the Nazis—once she was no longer muted by their tyranny.

In fact the Second World War saw the artist publicly derided for her degenerate works, and she lived out the war in cautious seclusion. A period that saw no public displays of her work, or opinion. Yet her art was spared exhibition in Die Ausstellung Entartete Kunst—the Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937—as many of her peers fled Europe to America to continue the movement.

But it was the compositional harmony of Höch’s work as opposed to the ‘anti-art’ of the Dada aesthetic that may have been the reason for her seeming erasure from Dadaist history. It was in the 1920′s that fellow Dadaists John Heartfield, and George Grosz decried her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair. Also the fact that fellow German Dadaists considered their female peers ‘charming and gifted amateurs’, suggests that left-wing art movements were not spared sexism, even in a progressive Berlin.

Höch was also an artist exploring the contradictions of her own identity, juxtaposed against a society in either post-war ascension or decline, whether in the darkening clouds of a pre-war Berlin with a tableaux of a fluid sexuality and social conscience, or with more than a glimmer of biting satirical wit.

The ‘Ethnographic Museum’ series, in which large heads from African sculptures appear on bodies of European women, have encouraged a didactic response amongst art historians in the past, suggesting that these works offer a critique of Germany’s imperial sojourns into Africa. If anything they were more likely to be a reference to the endless use of the female form in art, juxtaposing the totemic iconography of a ‘fertile’ African aesthetic of the time with the social freedoms of a 1920′s Berlin—but with the slight nuance of exploitation.

There are certainly references to the gaze of the viewer and objectification of the female form, and it’s socially disempowering consequences, bringing to mind; ‘The surveying woman is a man, the surveyed woman is a woman’, a notion that Höch would probably agree with, if not the language with which the concept is posited.

The stark nature of racial inequality in a 1930′s Germany was also referenced on several occasions in the artist’s work – a courageous act in the period of the Weimar republic.

There is also an anachronistic tendency to read a feminist agenda when viewing the works – yet the female figures of Höch’s photo-montages often express a knowing place, not only within the composition, but in history, both art history and cultural history; while creating mischief in their own social present.

Höch was not a follower of the strict formalist theory of Dadaism—hers was a detail of arrangement—abstracted social-conceptual imagery—often focusing on the female form and with a political vibrancy – a power to excite an anarchic aesthetic reflecting a period of tumultuous social upheaval.

But post World War Two Höch’s insightful and piercing aesthetic softened into lyrical abstraction. The artist’s anarchic social criticism was worn down by the fear of Nazi oppression—or maybe this was a reflection of a new found social and artistic freedom; her social commentary was quieter and her ‘attacks’ less ferocious.

One of the artist’s final works; ‘Lebensbild (Life Portrait) 1973′, is a complex photo-montage including images of Höch throughout her career. Having lived through one of the most eventful centuries in human history, she embraced the new media of ‘photo-matter’ often using it to comment on the very subjects it had captured.

Amongst the detailed collage is an almost hidden image from the Apollo moon landings and the famous image of ‘Earth Rise’. Höch’s figure is collaged into the image as an almost final act of mischief and a clever narrative of artist as attestor to the world. Human action processed through the eye of the artist as social conscience and political commentator of unmediated expression.

As Höch is not only observing the moon landing but peering over the shoulder of the astronaut, with magnifying glass in hand looking back at, and observing the earth. The most objective view of ourselves in history. A conceit to a lifetime of critical study and manipulation of the photograph, and a modest, almost hidden statement of witness to a lifetime of change, and an artist’s moral obligation.

Reposted with permission of New York Arts Magazine.