Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at the Clark Art Institute

The Demi-monde of Paris

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 14, 2009

The special exhibition "Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris," through April 26 during the off season when entrance to the museum is free of charge, is the kind of in house, small scale, dense and insightful exhibition that reflects the great depth and richness of the permanent collection of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass.

Theatre and the night life of Paris were particular passions of Sterling Clark and his wife, Francine, who had worked in French theatre, before their marriage caused a rift in the family. They shared a love of French art and culture and, along with Pierre Auguste Renoir whom they collected in depth, they particularly admired the work of Toulouse-Lautrec.

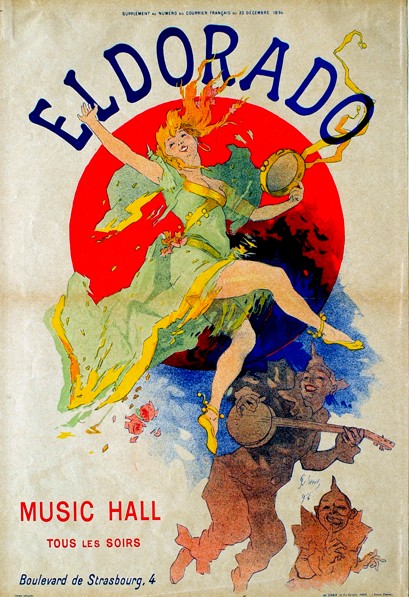

For the first time in fifteen years the museum is displaying its entire holdings of the artist and works from the collection that relate to the theme of Parisian life. While a small scale show, in just a few galleries, there are eighty works on view including several oil paintings and some original drawings but primarily lithographs including a complete edition of "Elles" and a sample of his well known posters for dance halls like the legendary Moulin Rouge. There are only a handful of works borrowed from other museums including vintage photographs of the dancer Loie Fuller from the neighboring Williams College Art Museum and a photograph of the performer La Goulue, loaned by Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

The warren of intimately scaled special exhibition galleries of the Clark were designed in another era for shows such as this that encourage us to get close to mostly small scale works on paper. One feels the urge to come to these Clark shows armed with a magnifying glass as well as an abundance of time and patience to absorb all of the fine detail. There is also a lot to read and study in terms of wall labels and signage.

This translates into a slow and methodical experience of the works with very few of the iconic images and posters that blow your socks off. At the end of the exhibition one is more in the mood for a cup of tea than a shot of absinthe. This is the more quiet and introspective aspect of an artist who often evokes the sweat, heat, and sexual energy of the circus, café, theatre, dance hall, and brothel. No artist more fully captured the spirit and flavor of fin de siecle Paris.

While mounting an exhibition of one of the leading French artists of his time one senses that the Clark, in the dead of winter, is cranking up the juice of its marketing and PR strategy playing on the persona and unique physical curiosity of an artist who is mostly known to the public as the freak portrayed by Jose Ferrer, in the Academy Award winning, 1952 film "Moulin Rouge" directed by John Huston.

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was born on 24 November, 1864, to the first cousins, Comte Alphonse and Comtesse Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec. Arguably, because of generations of inbreeding, he suffered medical complications. At 13 he fractured his left thigh bone and at 14 the right thigh bone. They never healed and ceased to grow. As an adult he was 4 feet 6 inches tall with the torso of an adult and the legs of a child. While bedridden for extended periods as a child he was given drawings materials to pass the time. Instead of the professions suited to his aristocratic heritage he was allowed to study art in Paris with a modest stipend. In constant pain he sought relief through drugs and alcohol. He died from complications of alcoholism and syphilis at the family estate at the age of 36 on 9 September 1901.

In a relatively brief career the known works by the artist include 737 canvases, 275 watercolors, 363 prints and posters, 5,084 drawings as well as some ceramics and works in stained glass. He is admired primarily for his graphic work particularly brilliantly colored and boldly designed lithographic posters for the Moulin Rouge and other night clubs. This commercial work also ensured exposure to the night life of Paris the better to study his primary subject. Surely his odd physical appearance assured him ready and unquestioned access to the dark side of Paris. He was a participant in and not just an observer of the demi-monde that he depicted.

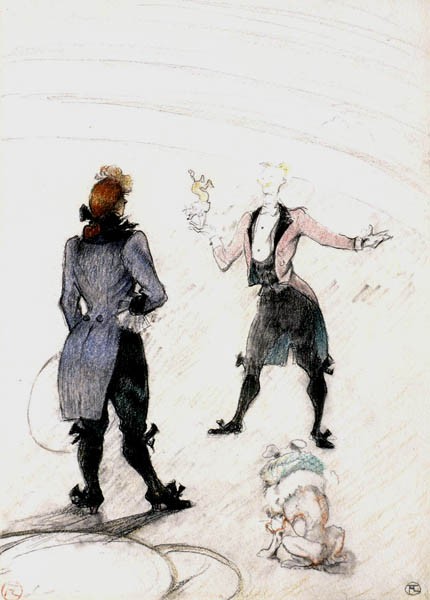

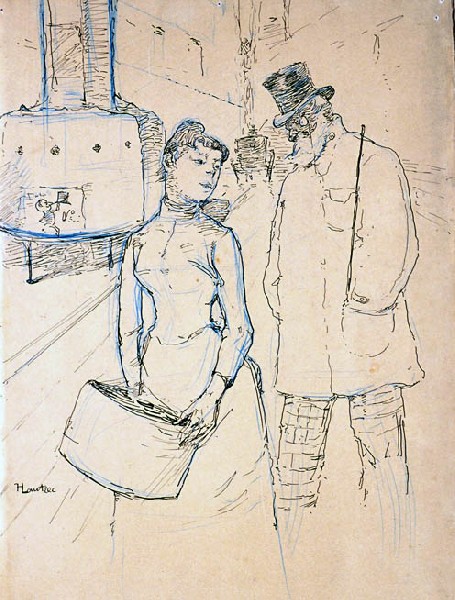

He took full advantage of this immersion in the underworld to provide stunning and insightful sketches of prostitutes and performers in their natural habitat. Often the work seems to hover on an uneasy edge between observation, illustration, and social commentary. Many of the women he depicts are rough and brutal. But there are also works in this exhibition that are tender and full of compassion.

Because his greatest accomplishment was in the realm of commercial art, marketing and advertising he is viewed more as a populist and illustrator than as an innovator. In the hierarchy of Post Impressionist artists he lacks the status of Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, or Paul Cezanne. In that sense he was more the Andy Warhol than the Jasper Johns of his generation.

A careful study of the exhibition, however, underscores that he was as inventive, avant-garde and experimental as his peers. One has to look beyond the subject matter to understand the formalist qualities of the work. Like others of his time he was influenced by the space and design of Japanese prints which were a rage in Paris.

In the color lithograph "The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge," 1892, for example, two women are flattened and condensed on a diagonal at the left side of the pictorial space. There is little detail other than the line and pattern of their costumes. Their identity is concealed from us and of little importance beyond depiction as types and signifiers of women of the evening. Leaning into them at a thrusting angle is the well attired Englishman. But the artist evokes a powerful device of casting him into a monochromatic shadow with sparing lines picking up details and accents of his persona. In a boldly graphic manner he had reduced the reality of such an encounter into its archetypal deconstruction. We get the sense of the moment depleted of any distracting detail. Similarly, in the poster for the dancer Jane Avril she is distilled to a flat and pulsating essence conveying more a logo than persona of the performer.

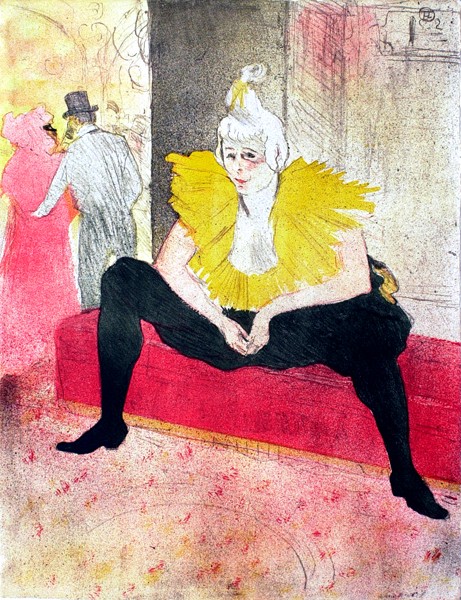

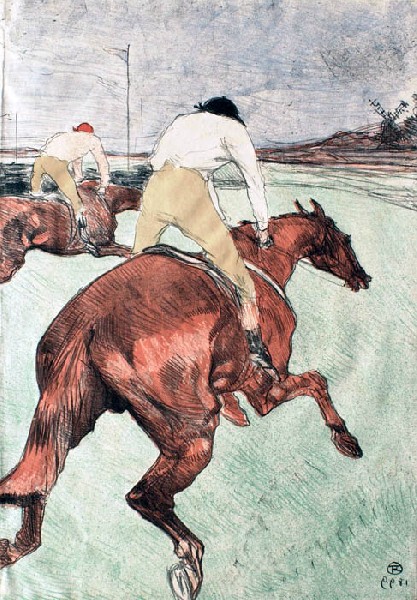

The familiar "Elles: Clown (Seated Clowness, Miss CHA-U-KAO)," 1896, presents us with the enormous mass and volume of the entertainer. She is seated with her legs in black tights sprawling out from an ungainly slumped over form. How different and absurdly cartoonish and comic compared to similar studies of dancers in repose by Edgar Degas. One also thinks of Degas in Toulouse-Lautrec's depiction of similar subject matter in "The Jockey" 1899. Where Degas was capable of the most subtle nuances the image by Lautrec is strident, bold and illustrative.

There is a quick and insightful touch to Toulouse-Lautrec at his best. One thinks of him in the bar, brothel and nightclub working furiously with pencil and pastel. Or in the print shop creating those inventive prints and posters. There are some great paintings but he belonged more in the field than in the studio. Standing before the easel only seems to slow him down. His work is about the action of fevered and frenzied observation trying to capture the kick and twist of the dancer, the arrogance of the performer, and the tawdry despair of a prostitute. It represents the sound and fury of a man not destined for long life. But one filled with the pain and suffering of which we are voyeurs. Viewing the work provides guilty pleasure.