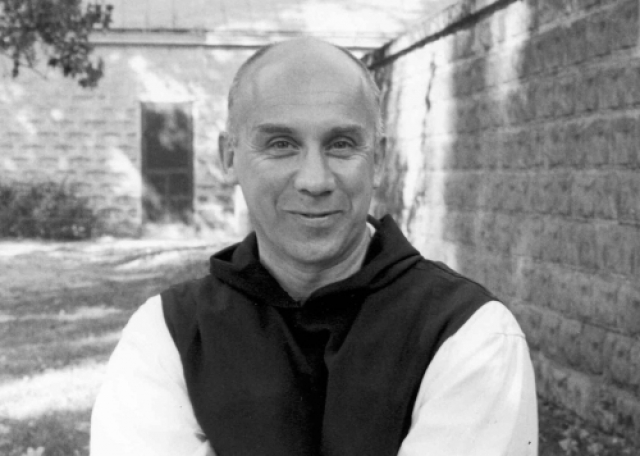

Thomas Merton's The Glory of the Word

Coney Island of the Mind

By: Martin Mugar - Feb 14, 2016

When I first read in the “New York Times Magazine” that BAM was producing “The Glory of the World”, a play celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of Thomas Merton’s birth, I thought it might revive my early and somewhat lapsed interest in his work, which had first spun its magic on me when I read “The Seven Storey Mountain”. That narration of his inner and outer journey toward a conversion to Catholicism while a student at Columbia contained a kind of yearning for truth that was reminiscent of my youthful desire to be an artist.

His description of life in New York City evoked a mix of anxiety and hope typical of the difficult start of any journey that knows what it wants to leave behind but is not exactly sure of where it wants to go. His later works written after years as a Trappist monk attempt a fusion of Christian and Buddhist monasticism.

He had observed that the meditation exercises in the Buddhist tradition in many ways were more refined and subtle than those of Christianity and sought to integrate them into the monastic tradition of the Church without changing the importance of Christian notions of salvation. At a moment when his drift toward Eastern thought was picking up speed he died accidentally from electrocution due to bad wiring in a Thai hotel.

The play's story line, according to the “New York Times Magazine”s article, is a centennial birthday party with eighteen celebrants, who toast him and I imagined would try to reveal something about his inner life and contribution to many facets of his intellectual and spiritual life: Catholic, Buddhist, Communist and Taoist.

I got my first warning that the play would be antithetical to my expectations prior to seeing the play from my daughter Eve , who is an actress in NY. A friend was told by her movement coach that some of the scenes were wild and wonderfully choreographed.

Originally performed in Louisville Kentucky not far from the monastery where Merton lived as a Trappist monk, it was funded by a local philanthropist, who won millions of dollars in Power Ball and written by Charles Mee collaboratively with the director Les Waters of the Actors Theatre of Louisville. It starts out well enough with the director playing Merton in silence with his back to the audience framed with Merton’s sayings projected repeatedly on the walls to either side of him.

Suddenly, the all male crew of actors breaks the silence when they burst onto the stage ready to celebrate. They are raucous and seem to function more as a group of bros than as individuals. As the celebration moves from scene to scene, it becomes clear that little wisdom will escape from their lips. In several scenes they quote famous mystics but before long find themselves spouting banalities about solitude originating from such pop icons as Lady Gaga and Christina Applegate. Some of the sayings seem not to mean anything at all, starting out with some weight but slipping quickly into absurdity. At times some of the men seem to distinguish themselves as older and wiser and I anxiously waited to hear something of depth coming from their mouths but all ends up platitudinous.

At one point a conflict erupts from the frustration between two characters about some unrequited love, although we never get a clear sense of the origins of this misunderstanding. The couple resolves the conflict by dancing romantically to “The Street Where You Live” as the rest of the cast joins in dancing in pairs cheek to cheek.

One critic of the play has asked why the playwright decided on an all male cast and suggests it may reference the all male life of the monastery that Merton lived in. Homoeroticism is not veiled in any way, especially in the aforementioned dance scene but also in the wild fight scene at the end of the play where one character threatens to insert a plunger in the buttocks of a naked man scurrying wildly around the stage.

A major dichotomy in the play exists between the solitary Merton and the undifferentiated mass of revelers. This dichotomy becomes heightened in the fight scene that meanders between food fight, orgy and prison riot until it reaches a crescendo of outright mayhem ending the play with the stage strewn with trash. It is said that Mee, a student of mythology, often uses Greek myth as the conceptual underpinning for his plays. In “The Glory of the World”, the actors start out playing shallow frat boys but devolve into Dionysian revelers.

Although no murder is committed the energy generated by the fight scene, which lasts fourteen minutes, gets close to it. This fight scene raises a question: Do these eighteen characters represent the limited emotional and intellectual capacity of the world that Merton wished to escape by entering the orders?

Their thoughts, as manifested by their shallow questioning and understanding of Merton, are a thin facade hiding their attachment to the world in its lowest common denominator of physicality. At one point the crowd breaks out into a body building show, where, except for the few actors who were probably not buff enough to participate, they try to out do each other in their ability to flex and flaunt their muscularity.

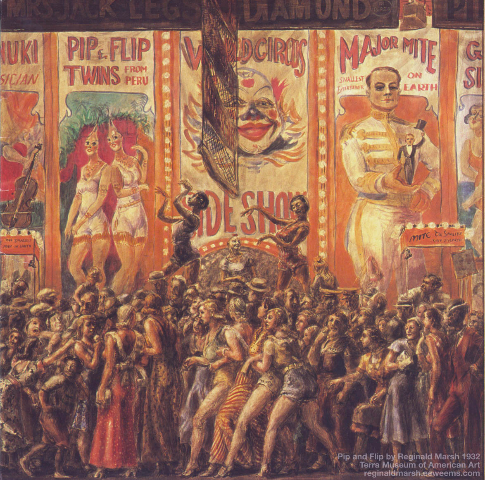

I got some hunches about the play’s meaning, as I thought retrospectively on a visit to the Brooklyn Museum prior to the play, where I saw a totally engaging exposition of the history of Coney Island. It started with paintings of the beach from the early 19th c, when it resembled Cape Cod, continuing to its heyday as the world capitol of mass entertainment in the Thirties, when there were three competing amusement parks, to its demise in the Sixties and Seventies and up to the present.

Its climax as the epicenter of mass hedonism seems embodied in the photo by Weegee of an overview of a massive horde of bathers in 1940 that was used as the basis of a funky collage by Red Grooms done in the 90’s. I recalled a book of poems that I bought in college by Lawrence Ferlinghetti called “The Coney Island of the Mind”. A little research led me to Henry Miller who coined the phrase in order to capture imagistically Coney Island as the epitome of the superficiality and crassness of mass capitalist culture. Of Coney Island he said:

“Everything is sordid, shoddy, thin as pasteboard. A Coney Island of the mind. . . . In the oceanic night Steeplechase looks like a wintry beard. Everything is sliding and crumbling, everything glitters, totters, teeters, titters.”

Upon reading this, my hunch was that there might be a parallel between Miller who left America behind to pursue an almost spiritual life of erotic exploits in France and Merton who as a child followed his artist father and his father’s mistress to France where he first encountered the glory of French Catholicism. In so doing, intentionally or unintentionally as in Merton's case, they turned their back on the erotic identification of the individual with mass culture that was so poignantly evoked in the poetry of Walt Whitman and was a touchstone for so much art such as Reginald Marsh, who is well represented in the Coney Island exhibit. For Miller sex was pursued with a religious fervor as a sort of vehicle for personal transcendence. For Merton it was religion in its concentrated monastic form that offered him a transcendence from mass culture and also the worldly suffering he experienced when his personal life fell apart after World War Two, with the deaths of all his family members in particular his brother who was killed in the war.

Maybe it is the fault of the play’s structure that the transcendent God that Merton encountered in his solitude as a monk is conveyed abstractly and weakly by the periods of silence that frame the play and in no way can function as a potent anti-dote to the shallow antics of the revelers.

Even the quotes of Merton that are projected on the walls of the stage express his own doubts about knowing the sacred. In the end the exuberance of the birthday celebrants is such ecstatic good theatre (one critic imagines that future generations of theatre goers will see the fight scene as one of the great fight scenes of all time) one gets the impression that the playwright comes down on the side of the boisterous physicality of the masses.

Maybe that is the meaning of the play’s title. In writing this article I kept typing “The Glory of the Word”. No! This play is about the overwhelming glory of the world. If you came to learn more about the sounds of silence and transcendence in Merton’s life as a monastic you will be sorely disappointed.