Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery Exhibition and Catalogue

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 16, 2021

Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

September 26, 2020 to January 23, 2021

Catalogue: Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes traces Andrews’ commitment to portraiture throughout his career. Featuring new scholarship by Jessica Bell Brown, Associate Curator for Contemporary Art, The Baltimore Museum of Art; Connie H. Choi, Associate Curator, Permanent Collection, The Studio Museum in Harlem; and Kyle Williams, Director of the Andrews-Humphrey Family Foundation, this book includes an expanded artist chronology with never-before-published photographs that narrate the life and career of Benny Andrews.

Format: Hardcover

Trim Size: 14 x 9 1/2 inches (Large-format)

Pages: 188 pp; 35 artwork color plates / 13 double-page detail spreads

Publisher: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Printer: GHP Media

Contributors: Jessica Bell Brown, Connie H. Choi and Kyle Williams

ISBN: 1-930416-62-8

$75

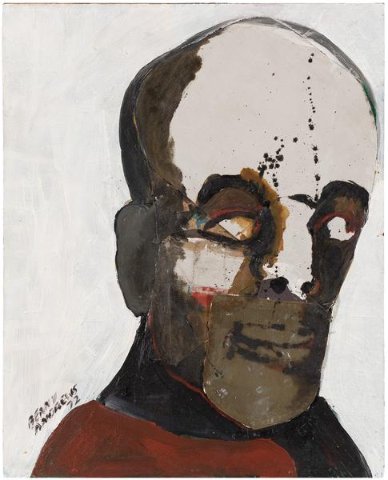

"I start out, I make a mess… I have to throw myself off so I don't copy what is right on top of my mind. Because if I just draw out or paint on something, I'm just copying what's in my mind. I'm trying to get deeper than that into my unconscious… I start out with a face and when I get a face that conveys a feeling to me of a real person, and I mean in feeling—I don't mean in realistic photographic likeness, but I mean feeling. When I get some that looks like a real face then I'm on my way… A cardboard person, no matter how real their surroundings are, [is] still cardboard. So, that's what I'm trying for... some kind of strength. Whatever it is depends on whatever I'm trying to say—happiness, love, all those kinds of things. But if I get a real person before the eyes, then I'm on my way.” Benny Andrews, 1968

The work of Benny Andrews (November 13, 1930 – November 10, 2006) is complex, compelling and problematic. Let’s consider his statement “I start out, I make a mess…”

Seen through the Eurocentric lens of mainstream art history and criticism it is, arguably, just that; a mess. Widening the scope of inquiry and critical analysis, however, allows for a broader and more empathetic interpretation. The approach toward “mess” is an issue of intentionality. To what extent was it the deliberate action of the artist or the reflection of ineptitude and a lack of skill of execution?

In 1971, at her request John Canaday, the conservative art critic of the New York Times replied to Eleanor Hass of the Studio Museum of Harlem.

Dear Ms. Haas;

I told you I would give you a memo of my reactions to Benny Andrews’s ‘Symbols and other works.’ I saw them on Tuesday, and here is my report, with a carbon copy for Mr. Andrews, if you want to send it to him.

I was of course interested in the work, but I think that more than anything else, I was puzzled. I could never decide whether the crudities of his paintings- and collage style were intentional for expressive effect and where they were the result of technical limitations. It is imperative, I think, that they be recognizable as one or the other. The crudities of a primitive master may be very expressive but mere crudity is not a guarantee of expressiveness. The crudities of a highly sophisticated artist may also be expressive (witness DuBuffet), but the premise of sophistication must be established in order to make them so. There is no middle ground. My confusion was compounded because Benny Andrews’ drawings have a sophisticated finish that makes the quality of his other works even more ambiguous. Also, in a work as large as the ‘Symbols’ triptych, I would like to see a tighter compositional scheme to harmonize with the elaborately worked out allegory.

Signed

John Canaday

A careful examination of the work reveals that the use of collage, building up relief surfaces and painted passages, attains a high bar of skillful execution. When viewing intuitive works of art there is an impulse to assign to it ease of execution. Particularly in the history of expressionism. There is often a complex process by which artists reject and overcome their academic training to delve beneath the substratum of civility to unleash more primal forces.

There is a trajectory of this from Picasso’s 1907 “Les Demoiselles d’Avigon” to deKooning’s “Woman 1” 1950-1952. With time they came to be regarded as game changers.

So there is a time frame and process entailed with coming to grips with the work of Andrews who, in addition to being an experimental artist, was a social activist, scholar, educator, and arts administrator.

In 1969 in protest of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s insensitive and ill-conceived exhibition “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968” he co-founded Black Emergency Cultural Coalition. From 1968 to 1997 he taught at Queens College and the City College of New York. From 1982 to 1984 he took a leave from teaching to serve as Director of the Visual Arts Program of the National Endowment of the Arts.

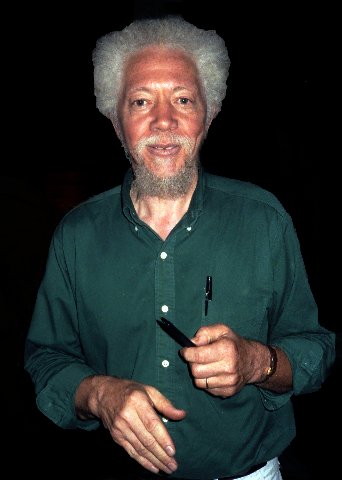

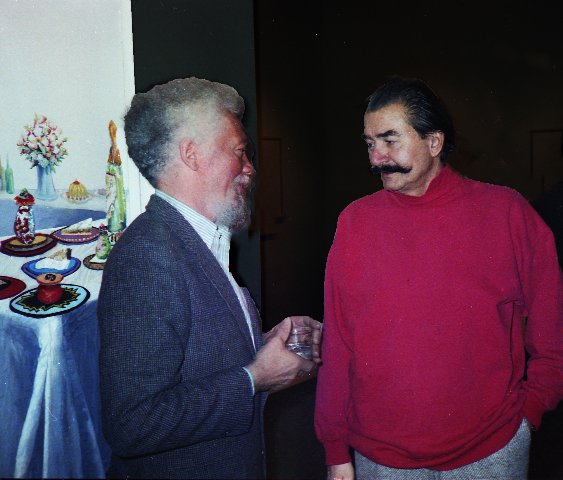

It was around that time when, by serendipity, we were weekend guests of Rhoda Rossmore in Provincetown. She was a generous patron of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. I was researching the art colony and was greatly assisted by the institution’s director Ellen O’Donnell her then daughter-in-law. There was lively dinner conversation and I vividly recall him disclosing that my investigative arts journalism was read and discussed during an NEA meeting.

Benny had a long association with Provincetown where he had his first one-man-show in 1960. We had much to discuss and that led to an invitation to visit the New York studio. He was sharing the small space, alternating every few months, with his brother Raymond (1934-1991) a novelist.

They were sons of George Andrews a Georgia sharecropper and self-taught artist. Because their labor was essential Benny could hardly be spared and was the first in the family to graduate from high school. Community college followed but he lost the scholarship because of poor grades. He enlisted and served in the Korean War. That qualified him to attend the Art Institute of Chicago on the GI Bill. There he was taught the techniques of abstract expressionism. It was also when he was first exposed to a museum.

In Chicago he first experimented with collage combined with painting. In 1957 he created the seminal “Janitors at Rest.” Significantly, they were African American workers.

“I placed the two little wads of tissues on a stool in front of my newly stretched canvas and sat back and started to think, Who are these men? They are the school janitors to us, Black and White, but in their minds they were much more. Yet here I am trying to think of some way to express my feelings for them that transcends the superficial jobs that they are stuck with, but how? I started fingering the two wads of paper and I thought, ‘Why not paste it on my canvas with no prescribed idea of designs or even picture, just paste it on at random. I know it is representative of an environment that they exist in, so if I put that on my canvas, and started playing around with ideas of them and so forth, maybe I’ll come up with an idea that is not so commonplace.’ I did that and then I started painting their faces. I smeared paint. I kept turning the canvas around, and I even went back to the men’s room a couple of times to talk with them that afternoon. I started working with collage that way, and I have been using it ever since.” Benny Andrews

The excellent catalogue for the Rosenfeld Gallery includes a dense chronology. We learn that the artist kept diaries of events and studio sales, accordingly, he is well documented. This included reviews which became ever more laudatory. As his reputation developed on many levels, that led to numerous exhibitions, grants, awards, and museum acquisitions. He was a pioneer and activist of the movement of African American art and today is regarded as one of its seminal masters.

The essays “In Excess of Realism: Benny Andrews’ Composites” by Jessica Bell Brown and "Benny Andrews and A Contemporary Black Figurative Tradition" by Connie H. Choi contextualize him as part of that movement.

In the 1980s, I was approaching Andrews from another direction. I was commissioned by David Anderson Gallery to write the catalogue essay for a traveling exhibition of Lester Johnson (1919-2010) organized by the Westmoreland Museum of Art. Anderson was the heir of gallerist Martha Jackson. Lester was represented by her as was Bob Thompson (1937-1966). I worked with Lester through gallery director Carl Hecker.

Lester spoke in depth of his discussions at The New York Artists Club where Irving Sandler was program director from its founding in 1955. It was dominated by abstract artists but Johnson spoke on panels focused on a return to the figure. MoMA got that wrong with the exhibition New Images of Man in 1959. The emerging movement of figurative expressionism was overwhelmed by pop art. Artists of the group came to be a lost generation in the canon of contemporary art.

Arguably, Andrews was a part of that aesthetic particularly through time in Provincetown and its progressive Sun Gallery. The figurative expressionist movement morphed to New York’s artist-run Hansa Gallery, (1952-1959, 70 East 12th Street, Fall 1952 - Fall 1954, 210 Central Park South, Fall 1954 - Summer 1959.) Its directors were Richard Bellamy and Ivan Karp.

That aesthetic led to formation of Rhino Horn with which Andrews exhibited. Rhino Horn artists included Jay Milder, Peter Passuntino, Bill Barrell, Ken Bowman, Michael Fauerbach, Peter Dean, Andrews, Nicholas Sperakism, and Leonel Gongora.

In 1986 I was guest curator of Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emilio Cruz, Earle Montrose Pilgrim, and Bob Thompson for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. The exhibition traveled to the gallery of Northeastern University. I chaired a discussion of the work with African American curator, Edmund Barry Gaither, and social justice art historian, Patricia Hills. I published an essay about the exhibition in Provincetown Arts Magazine. Of interest to me was the relationship of four figurative artists of color and the Provincetown community. The colony was long notable as a laboratory for developments of the New York School. That was particularly true for the summer-long event Forum ’49.

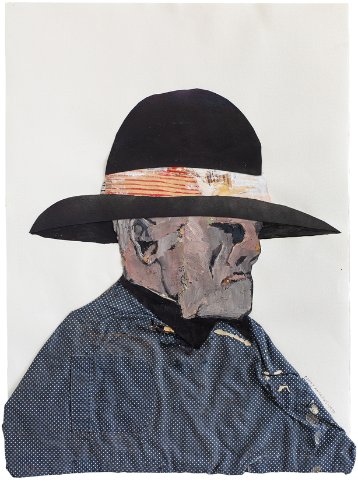

One commonality among these artists entailed attempts to unleash the internal impulses of expressionism. The intent was not to depict how the subject looks but how it feels. That empowered release from representational realism and a new approach to figuration. At Yale, Lester described having his students draw the figure using their other hand. Instead of starting with the head they approached the model starting from the feet and working up to the head. That trope informed Johnson's early series of large heads and “Men in Hats.”

From my time with Benny I was impacted by the broad range of his interest in the work and ideas of other artists. That was exemplified by his mandate for the NEA. It was challenging to engage with him. With tact, humor, and provocation he came at you from all sides simultaneously.

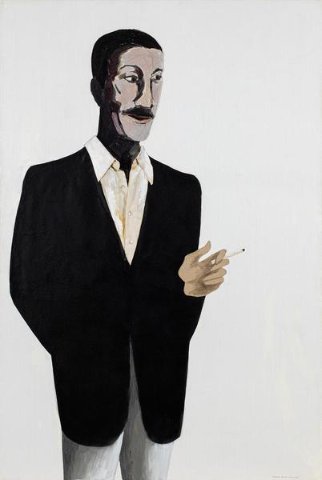

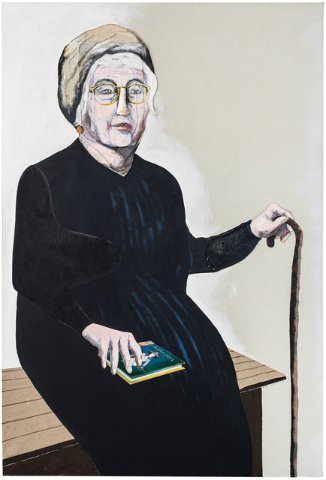

His humanism and range of empathy is well represented by portraits in the Rosenfeld exhibition. There are depictions of black folks derived from his Southern roots. We experience other artists such as a very elegant Norman Lewis in a formal black suit or fellow portrait painter Alice Neel. She is rendered on an overscaled canvas because he thought of her as larger than life.

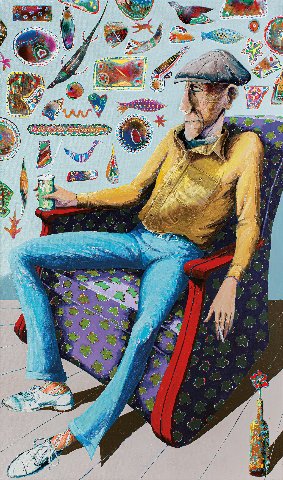

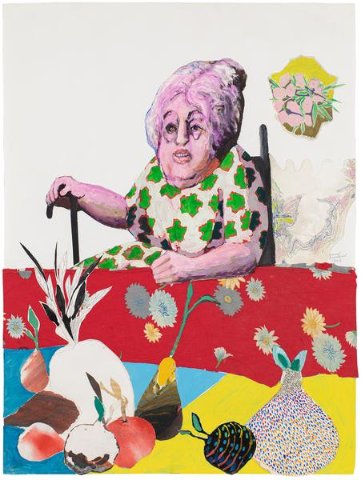

There is a revealing and poignant depiction of his father George. C. Andrews. He is depicted in an arm chair with a can of beer in one hand and a dangling cigarette in the other. There is an array of small objects in a pattern on the wall behind him.

Primarily the figures of his paintings hover in space and ersatz white light or sound. They are not tethered to a landscape. Some works, however, have objects that suggest nature or an environment. The portrait of his father uniquely situates him in a living room. It may be informed by the artist's take on memory. Is the environment, literal, actual or an imagined creation? What do all those objects on the wall individually, or as a pattern, tell us about his father?

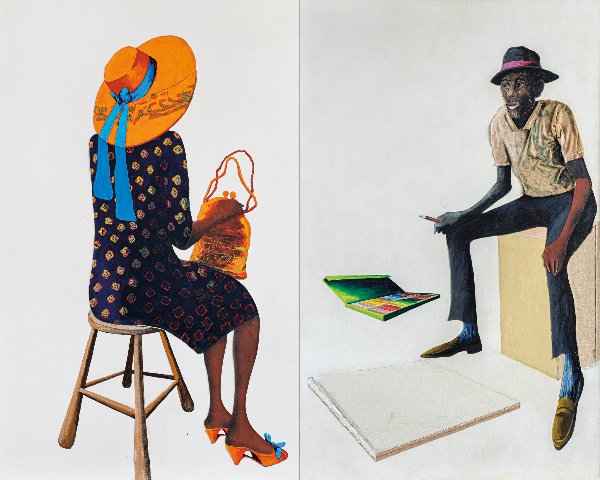

Particularly revelatory is the diptych “Portrait of the Portrait Painter.” On the right, the artist is seated on a box looking down at a blank canvas. There is a pencil in his right hand and to the right on the floor is a box of colors. The left panel shows his subject in three-quarter rear view. We do not see her face. Seated on a studio stool she wears a patterned dress. On her knees she clutches a purse. Both artist and model wear hats which is a familiar motif of the artist. Hers is more elaborate; straw with a blue ribbon that hangs down her back. The image is reproduced on the front and back covers of the catalogue.

The paintings of Andrews are about what they are not. There is a consistent theme of what he chose to eliminate. In some works, particularly the early ones, part of depicting a head or portrait entails what is left out. That we don’t see the entire form does not mean that it’s not there. That process of completing the image is left to the viewer and is a means to further involve us with the emotion conveyed by the work.

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought social justice, diversity and inclusion to all aspects or the art world. Benny was a pioneer of that movement. It is a signifier of progress and material value that a major New York gallery represents the Andrews estate. This is their third exhibition and it is accompanied by an extensive catalogue.

Within figurative expressionism and Rhino Horn, Andrews conflated the black experience. He invented that through the use of materials. There were elements of what his subjects wore like the coveralls of sharecroppers. That helps to conjure the spirit of the sitter by providing the scent of a visual metaphor. It is a technique deeply rooted in black culture and its use of ritual objects. The work owes as much to tribal art as the avant-garde use of Dada's found object and read-made.

Arguably, the works of Andrews and his peers have been shunned as a mess. Surely it was off-putting for the mainstream art world. With hindsight, we are coming around to the notion that it may have been a mess, but a holy mess. As much a mess as life itself. Which these artists did their best fully to express. Hopefully, closer attention to Andrews will help to see his work in the broader context of its aspiration and kinship with fellow travelers.