Salome

West Bay Offers Solid Production of Strass's Classic

By: Victor Cordell - Feb 16, 2026

To those unfamiliar, opera may seem a staid performance art for the aged, stuffy elite. Of course, aficionados know opera as a hotbed of intrigue, betrayal, and all manner of violent death from murder to war. And opera played such a profound role in Europe’s culture, especially in the 19th century, that state and local censors ensured that salacious and potentially disruptive political themes didn’t make it to the stage.

In 1905, with somewhat more relaxed censorship, Richard Strauss’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome premiered. In his home country of Austria, however, Vienna’s censor forbade it, so that the premiere had to be given in Graz, albeit, with luminaries such as Puccini, Mahler, Berg, and Schoenberg in attendance. It was initially banned in Britain, at the Met, and elsewhere, but its successes, particularly in Germany, eventually opened doors.

The ban-birds were offended by the vulgarity of the script, which is decadent even within the context of opera. A summary of the plot, which extrapolates fancifully on the Biblical story, is that the psychopathic Salome’s lust for Iokanaan (John the Baptist) is unrequited and spurned, so she demands that she be brought his head. Her dictate is fulfilled. The horror of the murder was enough to offend censors in Christian countries, and the erotic “Dance of the Seven Veils,” which precipitates the beheading, added to the calls for redaction or rejection. And though the music wasn’t a basis for censorship, its dissonant violence challenged accepted norms.

Led by a sizzling soprano in the central role, exquisite supporting players throughout, and a sonorous and responsive orchestra conducted by Jose Luis Moscovich, West Bay Opera offers a compelling rendition of this powerful work. While it is a traditional production with an attractive period set and costumes, you can already tell, that doesn’t mean it’s tame.

More than most operas, Salome rises and falls on the performance of one artist, the title character, who dominates the action once she makes her appearance. And Strauss’s music places huge demands on a Salome’s vocal strength, endurance, and range. In her Bay Area debut, Joanna Parisi gives an enthralling performance with a voice that reaches the outer limits of what a human is capable of. With house-filling power and crystalline clarity, her Wagnerian dramatic soprano fulfills every need of this role. Yet, her performance here and her history of diverse roles reflect the young, talented artist’s lyric abilities as well.

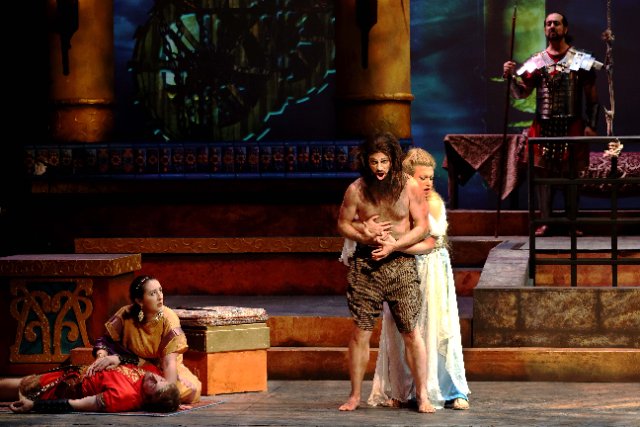

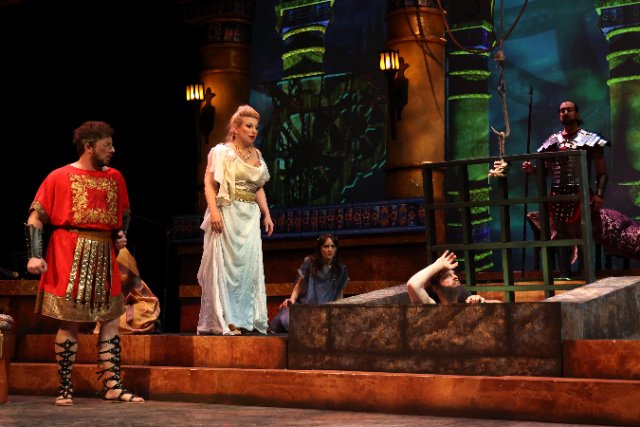

In this story, the married but feckless King Herod (steadfast tenor Will Upham in an ambiguous and ambivalent role) yearns for his stepdaughter, the 15-year-old Salome, who disdainfully rejects his approaches. But when he asks her to perform the dance of the seven veils, the petulant teen agrees if he will grant her a wish.

Of course, Herod is shocked when he learns of her horrific wish, but the question is - what does his acquiescence say about the character of the king when he reviles the command that he gives? Or what of Herodias (the formidable mezzo Laure de Marcellus who sometimes goes toe-to-toe with Parisi in the high, harsh notes), his bloodthirsty wife and mother to Salome, who revels in the debauchery?

In some productions, the singer of Salome also performs the dance, while in others, a preferably lookalike dancer substitutes. In this case, Parisi sashays sexually but is also joined by dancer Lydia Lathan, who acts as an attendant in the interesting choreography which plays to orchestral music that reveals both Arabic and Viennese strains. While Parisi is not as smooth or nimble as Lathan, she is most effective when provocatively twirling her unfurled hip-length blond hair and writhing on the floor.

Parisi’s dramatic acting excels in the closing sequences before the beheading when it is unclear whether she regrets her wish and after in her mad scene. Conversely, some early missteps with curious actions and posturing by her and others seem somewhat comic and break the dramatic trance.

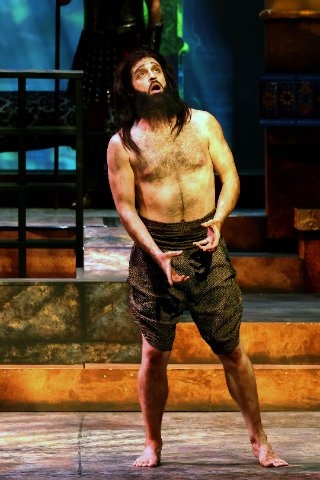

Another potential staging issue concerns the offstage singing of Iokanaan, as any singing behind the scenes can get lost. To begin with, Nathaniel Sullivan as Iokanaan has a strong and agile voice and when bedecked for it, fits the part well (i.e., in real-life he appears more a Clark Kent, but he transforms into a primitive-looking Superman type). The solution is that rather than singing from the wings, he sings from the cistern in the middle of the stage in which he is imprisoned. He also uses a homemade, unamplified megaphone, so that he comes through loud and clear.

Salome is structured as a stage tone-poem, with no set pieces, yet some sequences are separable such as the stunning and energetic duet when the religious Iokanaan emerges from the cistern to Salome’s lascivious appraisal of him and the vigorous quintet of five Jewish men. While the music is often harsh and dissonant, it is tonal and often in the Romantic vein. Strauss also uses a number of identifying leitmotifs, as well as some that are murky.

This opera was Strauss’s first success and began a string of hits. In 90 minutes or so, it is compact dramatically and musically, and West Bay’s production is well worth seeing, with some memorable performances.

Salome, composed by Richard Strauss with libretto by Hedwig Lachmann and based on Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, is produced by West Bay Opera and performed at the Lucie Stern Theatre, 1305 Middlefield Road, Palo Alto, CA through February 22, 2026.