Jo Sandman at the Danforth Museum

Discussing a Career in Black and White

By: Susan Schwalb - Feb 17, 2009

Jo Sandman: Once Removed

Danforth Museum of Art

123 Union Street

Framingham, Mass.

508 626 0051

Sept. 6- Nov. 9, 2008

Curated by Katherine French

Link to Danforth Museum

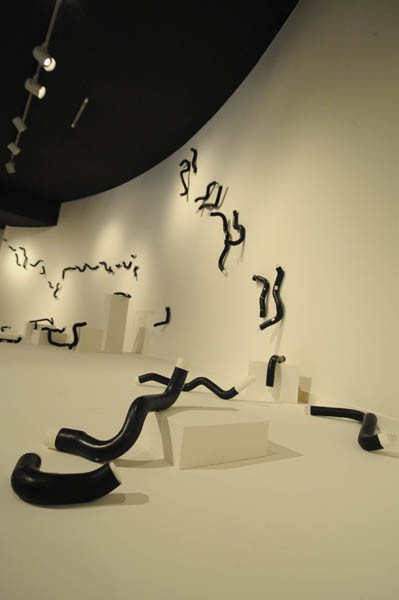

Entering The Danforth Museum one was immediately drawn to a large installation entitled "Continuity" that seemed to dance across the 40-foot long space. Small units of plaster of Paris and pieces of automotive hose wiggled and slithered on the wall, crawled over sculpture stands and reached the floor, giving the illusion of a huge three-dimensional drawing. Part of an impressive survey of more than 30 works of Jo Sandman's sculptures, drawings and canvases, it inspired me to visit the studio in Brick Bottom, Somerville, MA, to see photography (not included in the Danforth show) and to discuss her life and work.

Sandman was born in Boston where she has spent most of her life. She studied art at Brandeis University with Mitchel Siporin and in the summer of her junior year (1951) she was in residence at Black Mountain College along with Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. Sandman was galvanized by their experimental approach to materials. She soon fell under the "spell" of Robert Motherwell, who was teaching that summer, and began to paint on burlap during the day while making "Schwitters-like" collages at night. It was a heady time for a young artist and although John Cage wasn't in residence, his presence and influence (according to Sandman), was felt by the other artists.

After graduating from Brandeis she spent the summer at the Hans Hofmann School of Painting in Provincetown and then moved to New York City to continue study with Hofmann and Motherwell at Hofmann's New York School. Hofmann hired her as the school's registrar when funds ran out so that she could continue studying. As a student of Hofmann she was required to draw the model every morning in charcoal and then to paint in the figure with drapery and backdrops in the afternoons. Every Friday there were group "crits" of student work. Sandman joined The Club, which met at the Cedar Bar, where Frans Kline and Adolph Gottlieb held court along with many other artists.

A fellow student, Phyllis Manley, somehow convinced Sandman to go to the University of California, Berkeley, for her MFA (1954) where the influences of Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Paris were still in the air, and in that year Sandman's work turned abstract. She returned to Boston for the summer to visit her family and after experiencing a large and dramatic hurricane decided it was a sign for her to remain in Boston. With no job prospects, her father offered to pay for some "practical training" (i.e. secretarial school), but Sandman found a teacher's program at Radcliffe College and her father agreed to pay for that instead. While at Radcliffe, she met Walter Gropius who later employed her as a mural designer and color consultant at The Architects Collaborative (TAC), where she designed titles, murals and 3-dimensional works for local schools and institutions.

Sandman taught art at Wellesley College from 1958-63 and then, after a long pause to raise her children, at Mass. Art from 1981 until the present. Until the children were in elementary school, she often had only one day a week to work. In 1971 she was finally able to acquire a separate studio and joined the Boston Visual Artist Union (BVAU). With friends made through the BVAU (Martin Mull and his girlfriend, Todd McKie, Bob Guillemin, and David Raymond) they hatched a plan for a guerilla action at the Museum of Fine Arts/Boston to protest the lack of contemporary art.

An impromptu exhibition entitled "Flush with the Walls" was planned for the downstairs men's bathroom. On reconnaissance missions the male members of the group made floor plans for the show and invitations were sent out with a rubber stamp printed on sheets of toilet paper to a select group of friends, curators and critics. Arriving at the museum with small works on paper under their coats the group installed the show, and an opening commenced -- that is, until a staff member (Diggory Venn) used the bathroom. The exhibit lasted only an hour before the artists were thrown out; however, articles on the event appeared in Boston newspapers. The maintenance staff destroyed all the art works, but the group was subsequently granted a meeting with the curators of the museum. Not long after, in 1971, Perry T. Rathbone, the director of the MFA, relented to pressures from artists and critics appointing Kenworth Moffett as the first curator of contemporary art.

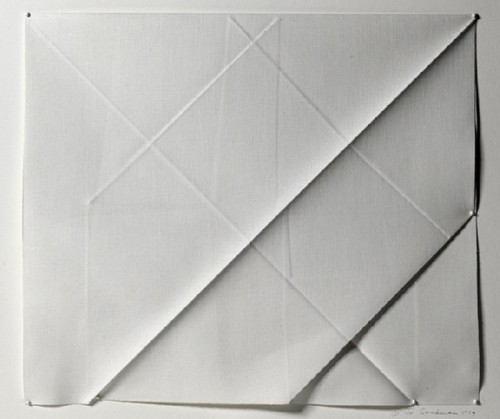

Some of the earliest works in the Danforth exhibition were produced shortly after the political action at the MFA. Highly minimal, these white-on-white pieces, originally shown at Sandman's first solo show at OK Harris Gallery in New York, were made by folding canvas onto itself to create a defined grid. A strong resemblance to the folded paper works of Dorothea Rockburne is unmistakable, and once Sandman saw Rockburne's work she abandoned canvas, turning instead to insulation silver foil and paper on board. Entitled "Tape Removal #030" and "Removal" these works have a strong linear sense; instead of folding, Sandman now used tape against the modulated silver foil so that the removal of the tape exposed a clean line that divided the artwork into a grid, giving the free surface a formal structure.

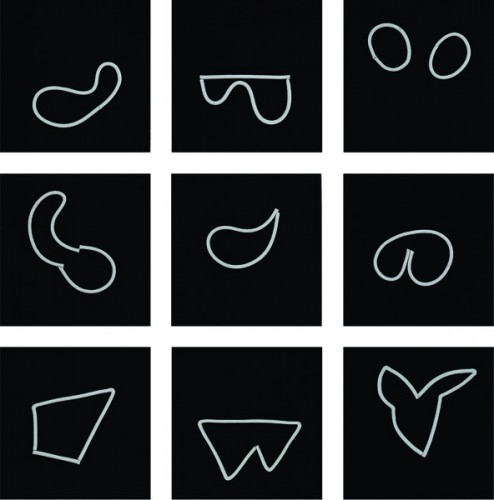

The work in the show most familiar to me was the Tarp Series made of found drop cloths, once an essential property of commercial house painters. Various installations from the early 1980s use these cloths; however, the Danforth show was only able to include several collage-like works behind glass. But it was still possible to get a sense of these conceptual pieces, in which recycled materials are used in an innovative manner. Continuing her interest in industrial materials, Sandman made a large series of drawings entitled "Artifacts of Air" in the late 1980s, using commercial caulk on sand paper. A record of ephemeral dust motes floating in the air, their biomorphic forms, placed inside square units of black sand paper; suggest a humorous version of ancient hieroglyphics from another civilization.

Since 1995 photography has become her primary medium. The first series consisted of photograms of found objects but soon the use of X-rays (originally of herself) dominated the work. Bold and quite scary, these photographs, recently published by Palm Press, remind us of our mortality. The most recent photographs, entitled "Thermal Drawings" begin as incense and smoke on fax paper, and are then photographically scanned and re-printed on etching paper to insure their longevity. Again, we see only black and white, and the abstract forms seem to suggest the presence of the artist's hand as it moves across the picture plane.

Sandman's career has been dominated by black and white, and I am immediately reminded of the 10-year period in Redon's life when he restricted himself to black and white drawings and prints. The deep blacks that Redon achieved through charcoal Sandman has created with smoke and other materials. Very few artists have made a preconceived commitment to avoid color altogether in their work, and when I asked her about this she really didn't answer me, but I suspect that one body of work led to another and somehow color never entered into her field of vision. In any case, we have to be thankful for a body of work that is extraordinarily diverse and original. The show at the Danforth was, for me, a moving experience of an artist's creative journey over a lifetime.

Susan Schwalb is an artist specializing in silverpoint paintings and drawings. She divides her time between New York and Boston and has written for Artscope, Art New England, and numerous feminist publications.