Deborah Kass’ Pop, Power, and Patriarchy

The Art History Paintings at Salon 94

By: Jessica Robinson - Feb 17, 2025

The history of art was always a boys’ club, and Deborah Kass, a gay, Jewish woman, was not included. So she broke down the door, pulled up a chair, and promptly flipped the script on the entire conversation. “I didn’t ask for membership, I demanded it.”

No, Kass didn’t wait for permission to speak through the language of art. She painted works that made sure her voice was heard —loud and clear.

In the 1990s, as identity politics was reshaping the art world, Kass gained notoriety by creating The Art History Paintings, a series of 12 works that challenge the exclusionary gatekeeping of gender, race, and privilege. By reinterpreting iconic styles and motifs, she forced a conversation about who is represented, who is erased, and who makes the rules.

If you missed them the first time around at the Simon Watson Gallery, “The Art History Paintings” will be on view once again at Salon 94 from February 19 to March 29.

Cleverly merging high art and pop culture, Kass places the modern art history “greats”-- Robert Motherwell, James Rosenquist, David Salle, Andy Warhol et al.-- alongside Disney cartoons and comic book heroes, interrogating the gendered and racial politics of art-making. “First I learned their language, and then I dismantled it.”

There’s something deeply subversive about The Art History Paintings—and not just because she’s hijacking your precious Modernist icons. What Kass does here is far more audacious: she’s peeling back the layers of patriarchy and privilege that prop up the art world’s canon, and then serving it back to us with a wink.

In “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” Kass deftly satirizes the artist David Salle: “I was riffing on someone I thought was very important, but I was coming at his work with a feminist perspective.”

Using the title of a book by James Joyce, Kass paints a splay-legged man boldly displaying his genitals. She then overlays the painting with a portrait of Picasso. It’s a visual mic-drop moment. “That the effect is offensive seems precisely the point: women are not supposed to do to men in art what men can do to women,” wrote Michael Kimelman in the New York Times.

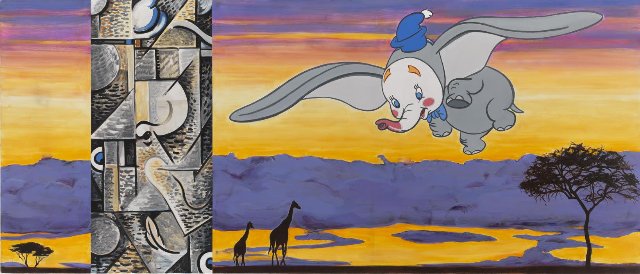

If that packs too much of a wallop, let’s pivot to something a little more PG – Dumbo. Yes, that Dumbo. In a playful riff on Walt Disney, Kass brings one of his most famous outsiders into the art historical arena. The floppy-eared, flying elephant mocked for his differences, struggling to fit in, has become a proxy for every artist, identity, and idea that has been systematically erased from the canon.

Kass’s Dumbo is a cultural icon representing the themes of bullying, prejudice, and discrimination — a sharp commentary on the persistence of exclusion—whether in museums or Hollywood.

Speaking of icons, enter Barbra Streisand. Kass’s portrait titled Before and Happily After, takes direct aim at the most famous Pop Artist : Andy Warhol. Kass unapologetically appropriates Warhol’s signature silk-screen portrait style overwriting it with her own story: “I replace Andy’s male homosexual desire with my own specificity, Jew love, female voice, and blatant lesbian diva worship.”

For Kass, Streisand was a lifeline: “Barbra is the pop diva who changed my life as a Jewish girl growing up in suburban New York in the ‘60s. Her sense of herself, her ethnicity, glamour, and her difference affirmed my own ambitions and identity. I identified with her completely.”

In Before And Happily Ever After, Kass plays on Warhol’s painting, Before and After – his black and white canvas of a nose. Created in 1962, the painting is based on a plastic surgeon’s ad for a nose job. The image is a simple left/right composition: a large nose shrinks into a daintier one.

Kass flips the concept both literally and metaphorically. She divides her canvas top to bottom, with the upper featuring a black-and-white profile of Streisand’s nose. Below, in cartoon colors, a pair of hands offer a penis (you read that right) to a naked foot, an exaggerated nod to mid-century advertising graphics of comic strips. It’s a study in contrasts—elegant monochrome meets brash color, reverence meets absurdity, divinity meets flesh. But what are they doing by offering a penis to the woman’s foot? Is this a spoof on Cindarella and the glass slipper? Kass leaves it deliberately ambiguous, forcing us to consider how women—especially those who carve their own path—are idolized, objectified, consumed, and dismissed—all at once.

With “Emissions Control” Kass lampoons James Rosenquist’s wide-eyed optimism about technological progress. This canvas is divided into three acts. On the left a phallic drawing nods to the eternal (and exhausting) link between male ejaculation and action painting. In the center nature explodes into chaos. And on the right? The End. Literally. Possibly a reference to the 1986 explosion of the Challenger Shuttle after takeoff- an abrupt, tragic punctuation mark on an era that believed machines and men could conquer the world.

For a change of pace we have My Spanish Spring, Kass’s witty, two-panel response to Robert Motherwell’s Elegies to the Spanish Republic. The top half of the canvas is Motherwell’s Elegies—black-and-white, abstract compositions— built from thick, repetitive vertical lines that the artist conceived as a tribute to the violence of the Spanish Civil War. The black forms, often bulbous and weighty, dominate the compositions like dark sentinels of mourning, while the alternating white spaces create a rhythm of loss and persistence.

On the bottom half of the canvas Kass counters Motherwell’s gravity with a cartoon of Ferdinand, the famous bull who refused to fight. Here he is smiling while kneeling in front of a bouquet of flowers. Is he admiring the flowers… or is he proposing to them? Contrasted with Motherwell’s stark, solemn abstraction, this painting is both charming and cutting: who says power has to look like struggle and violence?

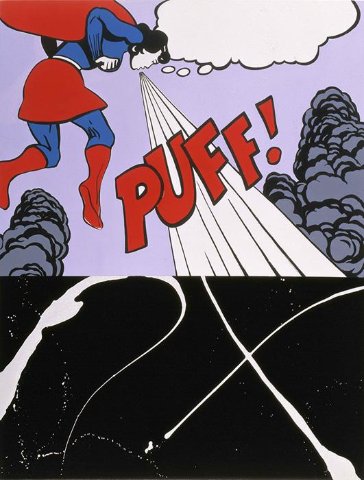

In Puff Piece Kass reimagines Wonder Woman as a superwoman with superpower. Rendered in Kass’s signature Pop Art style, Puff Piece depicts a comic-book-inspired Superwoman blowing air, a playful spoof on Roy Lichtenstein's mid-century comic book heroines.

The title is a clever pun—referencing both the act of blowing air and the journalistic term for an overly flattering but shallow article. By using a Superwoman figure, she is playing with gender roles in comic books, where female characters were often depicted as damsels in distress. Kass’s Superwoman is an agent of power, even though her "superpower" is simply air—it’s a sharp commentary on how women’s power is often dismissed as superficial.

Kass’s urge to riff on her forefathers was apparent as early as the third grade, when she created a comic strip called “Apple Sauce” based on Peanuts, and sent the drawings to the “Peanuts” creator Charles M. Schulz. And, he wrote back: “If you enjoy drawing cartoons, I would suggest that you keep at it. You never can never tell what it may develop into.”

The boys' club never saw her coming. But they should have. After all, Schulz warned them.

Now, decades later, The Art History Paintings are back—louder, sharper, and just as biting. The forces Kass set out to dismantle —patriarchy, racism, homophobia, and the elitism of cultural institutions— haven’t gone anywhere, making her work feel as subversive and necessary in 2025 as when she first picked up a brush.

Bottom of Form

The Art History Paintings

Salon 94

3 East 89th Street, New York

February 19 – March 29

.