Albany Symphony Orchestra plays new Greek music and Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony at the Colonial Theatre, Pittsfield

The Colonial Theatre's superb acoustics and a mixed concert

By: Michael Miller - Feb 18, 2007

Albany Symphony OrchestraDavid Alan Miller, Music director, conducting

Mythology

Giorgio Aristo, Tenor

Choir of St. Sophia Greek Orthodox Church

Panagiotis Liaropoulos: Ode for Orchestra

Moments in the Life of Orpheus (World Premiere)

Kostis Kritsotakis: The Voyage of Odysseus (World Premiere)

Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, Pastoral

The splendid Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield has so impressed me with its warm, present, and absolutely clear acoustics that I passed over the Albany Symphony's Friday evening concert at the great Troy Music Hall in order to hear the program there. On New Year's Day the Colonial was quite perfect for Kenneth Cooper's intimate Berkshire Bach Ensemble, which played with one to three violins per part, and I've been curious about what a full orchestra would sound like. The ASO appeared with eight first violins, a reduced ensemble, which fit comfortably on the stage and produced a more or less attractive chamber orchestra sound, perfectly appropriate for Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony in the second half of the program, but perhaps a little thin for the massive climaxes of Panagiotis Liaropoulos' Moments from the Life of Orpheus, which opened the program, but what the ensemble lacked in size, was compensated by clarity. I left the concert even more taken with the acoustics of the Colonial. If, in the Pastoral, the brass failed to assert itself, I'm more inclined to attribute the problem to the failings of the players. I very much that the Colonial will make the most of the first-rate chamber orchestras, both with modern and with period instruments, which travel North America each season.

I was also impressed with the Albany Symphony when I heard them play the Sibelius Second under David Lockington at the Troy Music Hall a few months ago.* Some of this quality came through in the first half of the program, but I have to confess my disappointment in the Beethoven.

Music Director David Alan Miller is to be admired for his commitment to contemporary music. It seems the ASO is constantly playing new pieces, many of them commissioned by the orchestra, in a great variety of different styles. What's more, the music is accessible, and, particularly in this case, directly related to the local community through the Greek origins of the music. It was particularly felicitous that Mr. Miller was able to engage the Choir of the Saint Sophia Orthodox Church to sing the choral parts of Krotis Kritsotakis' The Voyage of Odysseus. Both Mr. Liaropoulos and Mr. Kritsotakis, who were both present at the concert are relatively young composers. Mr. Liaropoulis has settled in Boston, where he pursued his studies and where he now teaches at the University of Massachusetts. Mr. Kritsotakis studied in Athens and London, returned to Greece, and has recently settled in Delaware, where he teaches at the Odyssey Charter School in Wilmington, which is devoted to Greek language and culture.

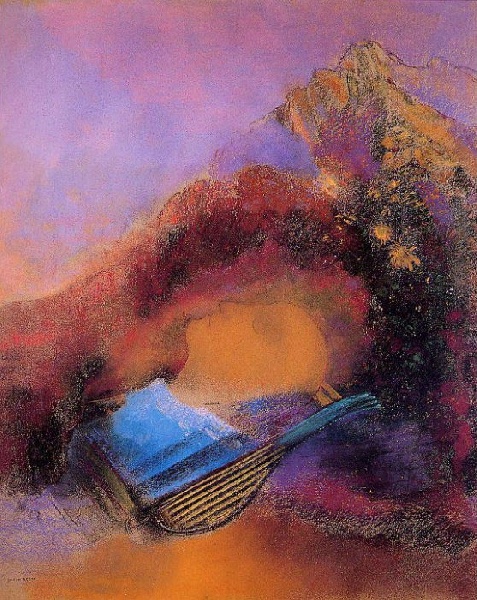

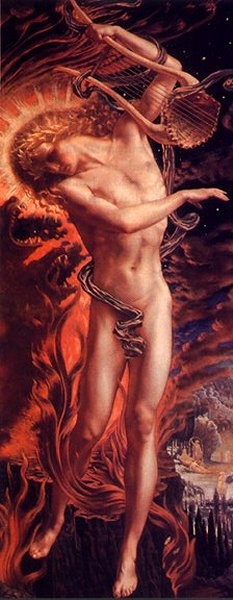

Their pieces were markedly different in method and style. Mr. Liaropoulos cast his Ode for Orchestra - Moments from the Life of Orpheus in the modernist style which has been current for at least the past sixty years, in which lyrical interludes for solo instruments are interspersed with loud dissonant climaxes with much brass and percussion, gestures entirely fitting for the story of the magical poet and singer, who, having freed his love Eurydice from death by charming Hades himself with his song, lost her again through his own unchecked feeling, and who in his grief shunned the female sex, even to the point of practicing—even inventing—homosexual love. In resentment a troupe of Thracian women or Bacchic maenads tore him limb from limb, throwing his head into the sea, which carried it, singing, to the island of Lesbos, where it continued to prophesy for some time. As a connection Liaropoulos uses fragments of the fragment of a choral melody from Euripides' "Orestes," virtually the only music we have likely to have been composed by one of the masters of the classical period. After a section dominated by a haunting flute melody, we eventually come to another quotation—this time from Mahler, played by Orpheus' instrument, the harp, reminding us of Luchino Visconti's film of Thomas Mann's contemplation of Greek love, "Death in Venice." Liaropoulos strings this out a bit more than Mahler himself, who had a keen sense of when his sweeter melodies might begin to cloy. Orpheus' dismemberment was appropriately noisy, and we leave him (or, more precisely, his head) singing on the waves. All in all, it was quite an effective essay in musical storytelling in a well-established orchestral language.

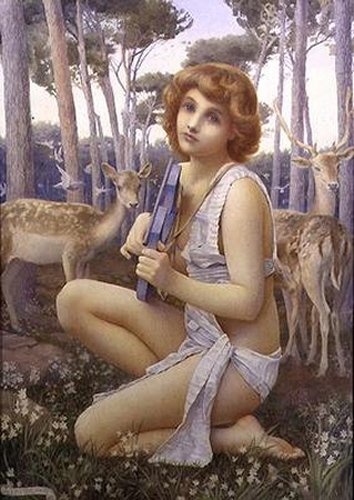

Kritsotakis' cinematic oratorio, The Voyage of Odysseus, soundly based on George Seferis' great poem, "Reflections on a Foreign Line of Verse" with additions by other modern Greek poets, including the compiler of the "libretto" Ioulita Iliopoulou, was tuneful, accessible, and quite moving. I was not surprised to read in the program notes that the composer had studied with film composer Manos Hadjidakis, second in fame only to Mikis Theodorakis, who will be most remembered by American audiences for his scores for the blacklisted Jules Dassin's Topkapi and Never on Sunday, the theme from which wafted Aegean breezes so gratefully into American bars, supermarkets and elevators during the 1960's. Even though the texts were mostly evocative in character, the music had a narrative sweep, as well as the vivid marine atmosphere of the poems. The orchestra played well, and the chorus of Saint Sophia sang with full-blooded feeling, as did the fine soprano and Giorgio Aristo, tenor, who also recited connective passages in English translation. However they were not helped by the unnecessary amplification employed for the performance. Their voices sounded too loud and too big, and the sound system was rather crude. Some artificial reverberation for the choir was called for at one point. It would have been better to use an offstage chorus. If the composer still felt electronic reverberation was necessary, it wouldn't have spoiled the effect of these fine and enthusiastic singers. Nonetheless, this absorbing work was rewarded with warm applause from the audience, Hellenes and philhellenes alike.

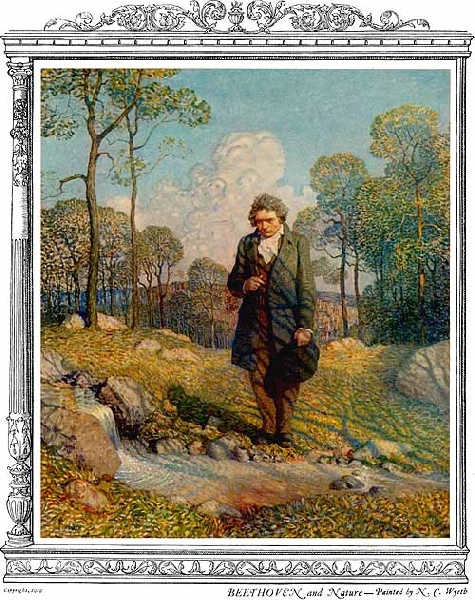

Last month I experienced something of an epiphany with Beethoven's Sixth Symphony, the Pastoral, at Symphony Hall, between Sir Colin Davis' splendid interpretation and Jan Swafford's perceptive program note, which drove home to me what Beethoven was actually up against when, probably eager to compete with his former teacher Josef Haydn, whose rustic oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons, had proven very popular. In order to avoid the rankest of clichés, he had to achieve a great imaginative feat in transforming the established pastoral motifs of the eighteenth century into a story, a fictive world based on personal experiences which resonated deeply with his innermost being—his walks in the countryside around Vienna. In this way his genial Pastoral Symphony is one of his most revolutionary and influential works. In it he created a new kind of program music to which we owe Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique, his Harold in Italy, Liszt's' A Faust Symphony, Strauss' Alpine Symphony, Ein Heldenleben, and similar works, not to mention Liaropoulos' Ode for Orchestra.

Any conductor who ignores or glosses over its programmatic content is making a big mistake. David Alan Miller is neither the first nor the last to breeze into this trap. Using reduced forces as he did, one of the great orchestras could easily manage the range of timbre and flexibility demanded by the symphony, but Miller seemed to have little interest in that. He was apparently striving for a slick, melodic, rhythmically snappy, two dimensional interpretation. Unfortunately his musicians for whatever reason were not quite up to even those inadequate goals. The strings, energetically led by concertmaster Jill Levy, showed some energy in the first movement, in which Miller established a breathlessly fast tempo. Their alert playing compensated somewhat for his smoothing over of the fragmentary dialoguing phrases in the opening bars, and, as limited as I found the interpretation, I could enjoy the playing. He also jumped into the dreamy second movement at a rapid pace, reducing it to a rush of shapely, but bland tunes. Remembering the psychological depths of Sir Colin's reading, which he achieved without any pretentious dragging, I began to feel some irritation. What's more, a certain sluggishness in the ensemble set in. Slight imprecisions of entry and response further impaired the music. I began to wonder if things might break down at some point. There was some nice playing in the woodwinds, but the brass sounded tentative and murky. The third movement, the peasant dance, was emphatic, but not particularly suggestive of the Brueghelian world Beethoven depicted. The horns, prominent in this movement, were still subdued, and the trumpets got lost. Miller seemed most engaged in the fourth movement, the storm, which gave him plenty opportunities for his balletic exertions , as well as an excuse to elicit violent thwacks from the tympani. The fifth and final movement, the "Shepherd's Song: Happy, Grateful Feelings after the Storm," was more relaxed, only to lapse into sluggishness again. The orchestra actually seemed weary by this point. The second violins, the violas, and cellos, the latter a little weak and insecure in intonation from the beginning, seemed unable to assert themselves against the first violins, who still showed signs of life.

___

*My favorable impression was confirmed in a odd way when, driving between Williamstown and North Adams one Saturday afternoon, I turned on the radio and heard music-making which I found absolutely absorbing within a few bars. It immediately made itself familiar, and I recognized the performance I'd heard at Troy a month before. Usually I dislike hearing music on my mediocre car radio, but the commitment and musicality of the performance came through over the grinding of the gears. The lovely balance and clarity of the sound, which I remember was recorded with a simple spaced quartet of microphones, was wonderful, reminding me of how Toscanini's Studio 8H should have sounded, if they'd done it right.