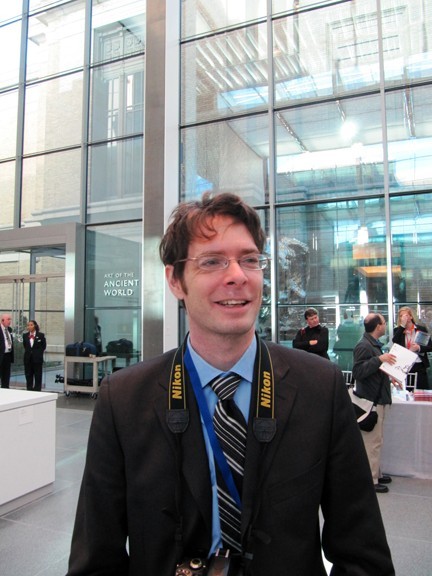

Art Critic Greg Cook Four

Maintaining a Critical Distance

By: Greg Cook and Charles Giuliano - Feb 18, 2011

During the late 1960s, before moving on to other publications, Charles Giuliano was the art critic for Boston After Dark. The weekly arts and entertainment newspaper later merged with the Cambridge Phoenix and was rebranded as the Boston Phoenix. During that transition it also expanded its coverage to include news, lifestyle and opinion. Today it is regarded as one of the nation's leading publications. There is a legacy of distinguished journalists and critics who have written for The Phoenix.

Currently Greg Cook is the critic for the Phoenix. To broaden the scope of his coverage, and commitment to serves the arts community, he founded an on line site The New England Journal of Aesthetic Research.

This lively and eclectic site reveals a broader and different aspect of his critical presence. Cook is one of very few on line arts sites to receive a prestigious grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation. It is a tribute to the energy and intergrity of his critical strategy.

Spanning more than four decades of covering the arts in Boston this is the final installment of an attempt by the critics to compare and contrast their experiences and mandates.

Charles Giuliano My final question to you is what different hats do you wear? How does that shape your vision as a critic? I know that you recently showed your work. Just what is your relationship to the artists, curators and gallerists you write about? Some critics are adamant about keeping a wall between themselves and their subjects. What’s your take on that?

Greg Cook Maybe I’m just pigheaded, but feel a need to work that hard to keep up with the national and global level art world in order to put local art into an accurate perspective. I feel like I keep up with it just fine by reading The New York Times and New York magazine and getting to New York now and again, and, you know, the ICA and sometimes even Mass MoCA. I get bored with everyone paying attention to the same thing.

Your description of working with “established but neglected artists” sticks out to me. I feel like Boston artists of all stripes tend to be neglected by our local institutions. I don’t get it. It seems as if it’s driven by anti-Boston myopia. But I know this is an issue in many American communities outside of New York and Los Angeles. Nearly everywhere institutional curators neglect local work. I feel like there must be worlds of neglected awesome weird art out there. The Lowbrow phenomenon is an example of a neglected art world that has since become prominent. But I feel like there’s a lot of other non-Lowbrow overlooked stuff. I’m not calling for grading on a curve. I just don’t think people realize how much artistic success—as defined by finances, appearances on the Circuit, and coverage the NY-based art magazines—is defined by where the artists happen to live.

To take one example, a third of the artists featured in Phaidon’s 2009 international art world survey tome "Painting Today" reside in New York. Not just show in New York—live there. The book included one Bostonian: John Walker. I struggle to understand why geography is seemingly such a dominant indicator of aesthetic quality in an international art world that repeatedly professes that everything’s global now and where you live and borders and so on don’t matter. You know, the world is flat and all.

As for wearing too many hats … I find the artist as critic thing confuses art people. And newspaper people, for that matter. So I don’t hide my life as an artist, but I don’t talk much about it here.

From around 1995 to 2004, I was part of a local art gang affiliated with the Cambridge art comics publisher Highwater Books. And I was working as a staff reporter for weekly and daily newspapers in suburban Boston, mostly covering things like cops and courts and schools and sewer systems, though I did some newspaper art writing around 1996 and ’97, then again between, say, 2003 and ’04. I stumbled into criticism as freelancer for the Boston Phoenix and Boston Globe in 2005. The following year I began The New England Journal of Aesthetic Research.

But I’ve not been devoting as much time as I’d like to my own art. All the fun writing about art—the day job—has gotten in the way of my own art making. Just the time it takes. But also because I’ve tried to maintain a “wall” of “objectivity” between me and my subjects, mainly by avoiding becoming too close to folks, or showing my own art here, or looking for teaching jobs at places that have galleries I’d like to write about. The first two are my natural inclinations. And the third has become something of a necessity because of the Great Recession. So the writing has been stymieing. And this depresses me.

I worry that being an art critic encourages my natural tendencies toward negativity and cynicism and righteousness, none of which are my most flattering traits. And the slog through all the mediocre stuff can be deeply uninspiring for someone who’s trying to make their own art. I don’t think people are really made to see so much art. You have to fight to avoid becoming tired of it all.

In the past year or so, I’ve let myself be more personally involved in the scene—in addition to my professional involvement. I mean cultivating more friendships. I had been avoiding showing here to avoid creating conflicts of interest with venues I write about. I’ve still not really been seeking local exhibition opportunities, and in fact I’ve turned down some because of this issue. I’ve come to believe that conflicts of interest are inevitable here because it’s such a small scene.

I keep wondering why I feel such a need to attend (critically) to other people’s work. It has to be more than my passion for art. It’s some sort of chutzpah to think that my opinion matters. I know why I keep pushing for a more exciting scene generally: I want the place where I live to be more exciting, more interesting, more inspiring. Your description of "decades of battling within the Boston arts community” stuck out to me. Because often I find myself feeling that way. And it's kind of depressing.

Reminds me of a debate I got into with someone who called me too negative, destructive, etc. He said I was sniping instead of working with others to improve Boston.

CG As to too negative, destructive, etc.—sniping instead of working with others to improve Boston.

It's not our job to "improve Boston" and a critic can never, by definition be "too negative." In whose opinion? There is no point to tolerating mediocrity. Being in the thick of the "battle" doesn't get you invited to a lot of dinner parties. It is always tricky finding friends and relationships in the art world. There is a lot of camaraderie among artists but a reluctance to embrace critics who are viewed as the enemy.

So it can be isolated and lonely to slog on. With, as you know, no reward and few if any perks. It's a strange gig.