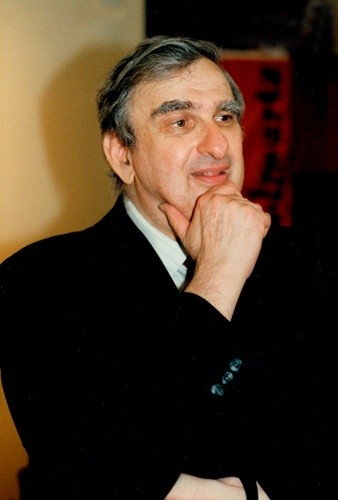

Henry Schwartz 1927 to 2009

Remembering a Second Generation Boston Expressionist

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 20, 2009

Following a retrospective at Brockton's Fuller Museum of Art, in 1990, Henry Schwartz fell into a severe depression. From 1991 through 2007, when he passed away, Henry was cared for by his brother David. This responsibility was then assumed by David's daughter, Paula Apsell, the producer of Nova on PBS.

During the years of his confinement, when he ceased to function as an artist, he was regularly visited by Arthur Dion, the director of Gallery Naga. Last year there was an "Awakening" link to Awakening article when Schwartz emerged from under the cloud of depression and was more communicative. While lucid he still suffered from the complications that recently took his life on February 16 at the age of 81.

For the first time in the decades that I have known him Dion was at a loss for words. Reached by phone he described how during yesterday's small, graveside ceremony, an intimate gathering of some fifteen family and friends, he stated that he was "unprepared" and spoke for only a couple of minutes.

While stating that he would answer any questions Dion told me "I find myself unprepared to make prepared, thoughtful remarks about Henry because my insides are still caught up in the experience of losing him."

In every sense, Schwartz was an enormous man with a huge persona who cast a long shadow over the traditions of contemporary art in Boston. He was a student of Karl Zerbe at the Museum School whom he acknowledged as his greatest influence. Zerbe, with Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine, formed the Boston School or the Boston Expressionists. Initially, critics like Clement Greenberg acknowledged the importance of Bloom in particular but they were later excised from the pantheon of the avant-garde in the ascendancy of abstract expressionism. It has taken decades, if ever, for Boston to claim a footing in the mainstream of contemporary art.

Given that unfortunate history I asked Dion to assess the position of Schwartz, both within the Boston tradition, as well as, global contemporary art. "Henry is the most interesting, ambitious, influential, and successful of the second generation of Boston Expressionists. He is the key link between Zerbe, Bloom, and Levine, and the subsequent lineage of figurative expressionism. A lineage that is better recognized today than it was twenty years ago and not as well recognized today as it will be twenty years hence."

Katherine French, the director of the Danforth Museum of Art, in Framingham, Mass. has made a significant personal and institutional commitment to collecting and exhibiting the Boston School and its particular focus on figuration and expressionism. In the fall of 2009, the museum is planning four, small, one person shows including Schwartz, his former student, Gerry Bergstein, Morgan Bulkeley, and David Aronson. The demise of Schwartz may impact the planning for those exhibitions. It is a matter of available resources. The museum recently acquired a work by Schwartz in an oeuvre that Dion estimates at some 500 paintings.

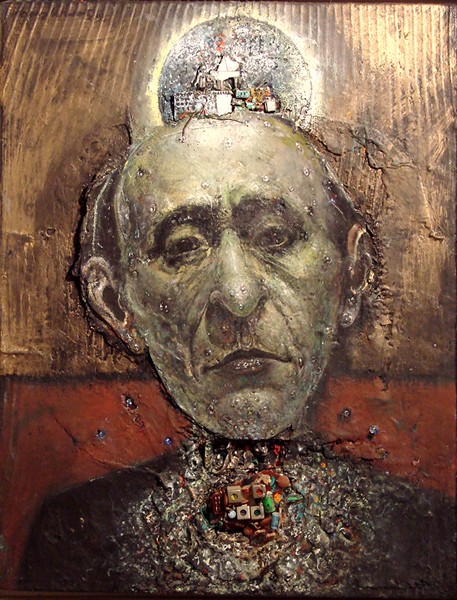

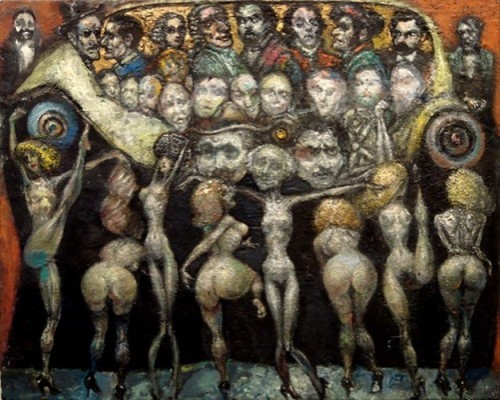

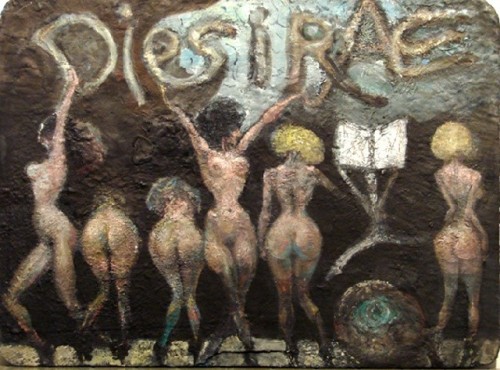

Asked for a statement on Schwartz French wrote that "Henry Schwartz was a visionary among visionaries. As an important member of a group of talented artists who studied at the Boston Museum School during the 1940's, Schwartz worked from memory and imagination to create quirky works of compelling elegance. Fascinated by music, informed by literature and art history, Schwartz was not held back by erudition. Instead, his wide ranging interests allowed for layers of meaning. What remained important was the painter's deeply emotional response to experience--his sometimes frightening, yet beautiful vision of reality."

Gerry Bergstein was particularly close to Henry, initially as a student, and later as a colleague in the faculty of the Museum School where he continues to teach. He wrote that "When I first decided to become a painter I was living in NY where I grew up. I was primarily attracted to surrealism and expressionism and loved Beckmann, Ernst, Chagall, Albright and an artist named Jack Levine. I studied at the Art Students League with a friend of Jack Levine's named Harry Sternberg, a terrific artist/teacher. The next year for reasons having more to do with love than art, I ended up at the Museum School. Henry was unforgettable at first sight.

"He was large and hulking, with a portable radio plugged into his ear playing classical music. The next year when I studied with him there was a radio in the class with the station locked to WBUR (then a classical music station). I discovered that he and I had a similar love of music and later discovered that my move to Boston was fortuitous because of Henry's love of a tragicomic, humanistic vision of art which identified the Boston School. I had no idea of this when I met Henry. It was a terrific accident. It turned out Boston with its tradition of figuration and its outsiderness from New York AbEx was the place I belonged. Henry was an integral part of my growing into an artist and an integral part of the history of art in this city."

My relationship with Henry was complex. He was so deeply involved with classical music, its images and icons, that I often found it daunting to enter and fully appreciate his intentionality. While the visual aspect was more accessible, with its expressionist angst and distortions, the subtext of iconography was often beyond my grasp. Arguably, I know more about what he was dealing with today than at the time when he was creating some of the most insightful and powerful work of any Boston painter exhibiting in the 1980s.

During gallery openings I would engage him in conversations that often seemed to tax his patience more than mine. Henry, it seems, was not inclined to suffer fools patiently and he took exception to probing what struck me as esoteric references in the work.

Today, in the process of preparing this piece, I pulled out the Schwartz folder from a filing cabinet. I looked through sheets of slides from exhibitions, clippings of reviews, mine and others. Also I encountered a couple of hand written letters. During my conversation with Arthur I asked if he had time for me to read Henry's letter. I did so with all dramatic emphasis and pauses for asides. There were howls of laughter as Arthur responded to Henry's unique style and insights. He thought the letter was remarkable and with his encouragement it appears below.

January 13, 1983 "Dear Charles, I am writing a prompt and I hope frank reaction to your review keeping in mind your just reproach to me that I had not been forthcoming on your last review. Since I was privy to your initial impressions of the show and your disappointment that there were not more symphony orchestras this time what you wrote- although certainly complimentary and respectful- had the aura of a job dutifully, if not pleasurably done. I am sorry if this is so, but I must remind you that you had my clear exhortation to write any review you pleased.

"Although nominally we have known each other many years, our telephone conversation was the first meaningful exchange we have had.- and this exchange uncovered many incompatibilities in our cultural outlook- which, in turn, pointed to the inevitable collision course that actually occurred.

"I guess there could have been no satisfactory resolution to this situation. It came down to choosing between gratifying yourself and gratifying me. That you chose to gratify me does not give me the satisfaction that I though it would.

"I think the conversation revealed also a fundamental difference in the conception of criticism. You expressed dismay at the ingratitude of artists who resented things you said without giving due acknowledgement to the exposure and publicity they were garnering. Don't you know how false this is? There must be a hard line drawn between publicity and criticism, and friendship has nothing to do with it.

"I take issue with you on the opinion you expressed about, what was to you, obscure references in art and their eventual values. But I am thinking of developing this in a letter to the editor and will not take it up further here.

"In a separate letter, Arthur Dion has written to Carla identifying certain errors in your text. (Carla Munsat was the editor of Art New England where the review in question was published.) It is unfortunate that you didn't catch me in, that Saturday PM, since a proofreading could have avoided those mistakes.

"I truly regret this episode, but I don't think it is without value, if we can both learn from it. Perhaps now we really can be friends? Cordially, Henry"

In another letter in the file, May 5, 1980, he thanked me for a review in the Patriot Ledger and requested copies of photographs of him and a friend taken during the opening of the exhibition. I suggested an exchange that resulted in his remarkable drawing of me in evening attire clutching the signifiers of my trade, a giant pen in one hand, and a sword in the other. More than a likeness, remarkably accurate the more so as it was drawn from memory, it seemed to capture his vision or my adversarial persona as a critic.

A final observation on Henry is offered by the artist, Domingo Barreres, a former student, and colleague now retired from teaching at the Museum School. "When I was his student, his painting class known as 'the tromp' was a favorite of all of us. We were sure we were learning something and we had something to show for it. 'The Tromp' continued to be an important part of the curriculum until Henry left. Other work done during the student years has gone to that place where student years' stuff goes, but the tromp was a keeper - unfortunately mine was snatched some time ago.

"Later, when I started teaching, we were more and more at odds. Henry was not partial to the changes the school underwent in 1968, under Bill Bagnall. I was all for change and then some! I was instrumental in enabling certain dramatic changes in curriculum and Henry never forgave me for that.

"In short, I liked Henry far more than he liked me, but we both had good reasons to feel as we did."

A lot of us felt that way. While acknowledging his importance as an artist, on a personal level, Henry was intense and could be a piece of work. Mostly, I regret the lack of direct contact after 1991 when Henry withdrew. He had been a giant who devolved into a shadow. Now that there is unsettling closure, with time, perhaps over decades, he will be accorded his due as one of the truly great artists of our time.