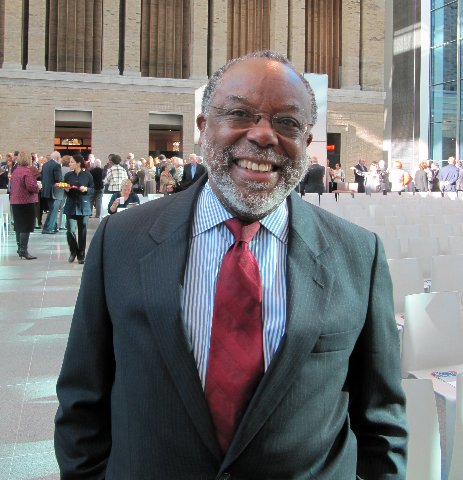

Boston Arts Leader Ted Landsmark

Discussed Transitions in 2000

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 20, 2020

This article is a part of a legacy and heritage series to compile an oral history of the fine arts in Boston.

Over many years of working with arts, development and higher education in Boston Ted Landsmark has been an inspirational visionary. As a rare African American in a position of authority and influence he has unique impact. He exerts a broad reach connecting diverse communities with common cause through the arts. In the art world he is respected for having earned his way onto boards of the Museum of Fine Arts and Institute of Contemporary Art. Generally, those positions are grandfathered through inherited wealth, social position, and Ivy league education.

A graduate of Yale University with undergraduate, law and MFA degrees Landsmark holds his own among elite powerbrokers. Pursuing a career in higher education administration he earned an insurance PhD in fine arts from Boston University. Raised by a single parent Landsmark has secured his status through sweat equity. He laments that there were few role models and mentors along the way but he now functions in that manner for those who have followed.

He is currently Distinguished Professor of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and Director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University.

He attended Stuyvesant High School in New York and St. Paul's School in New Hampshire, and earned his Bachelor of Arts, Master of Environmental Design, and Juris Doctor all from Yale University. He was a political editor for the Yale Daily News, and was part of the Aurelian Honor Society. He then received his Doctor of Philosophy from Boston University in American and New England Studies.

Landsmark served as the President of Boston Architectural College from 1997 to 2014, and as Chief Academic Officer at the American College of the Building Arts from 2015 to 2017. He has been a faculty member at the Massachusetts College of Art, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and the University of Massachusetts Boston. He has also served as a trustee for numerous arts-related organizations in Boston including the Museum of Fine Arts, the New England Foundation for the Arts, Historic New England, the Institute of Contemporary Art, and the Design Futures Council. In 2014, he was named to the Board of Directors of the Boston Planning and Development Agency by Mayor Marty Walsh.

The following interview was held in his office at the Boston Architectural College on May 17, 2000. Several years ago, we arranged for another meeting at the end of the day at BAC. As fate would have it that day power went out in the Back Bay. The meeting was cancelled and an attempt to reschedule was unsuccessful.

Charles Giuliano Are you a native Bostonian?

Ted Landsmark I’m 53 today and was born in Kansas City Missouri. My father was there in the service and my mother was there briefly. My parents separated long ago and I was three at the time. Landsmark is my mother’s maiden name. Carlyle, my middle name, is my grandmother’s maiden name.

Both of which names I took when I moved to Boston. I came here to work at the law firm of Hill and Barlow. I am a lawyer and also studied architecture. Hill and Barlow represented most of the major architects in Boston. I worked with a firm retained by architects, developers and contractors. The firm was politically oriented. Mike Dukakis, Bill Weld and Jock Saltonstall were with the firm at that time. Alumni of the firm have gone on to do interesting things. Reginald Lindsay is a Federal judge. Doug Fou practices conservation law and others have become professors.

I was an undergraduate major in political science at Yale with a minor in art. I remained for Yale Law School and its School of Architecture. I was in classes with Hillary Clinton and also knew Bill when they were law students. It was an interesting time when I was there from 1969 through 1973.

CG What led you to Yale?

TL I was in the NY public schools. I met a seminarian through my church who was a Yale alumnus who urged me to apply. New Haven was just an hour and a half north of East Harlem and the projects but it was a conceptual leap to apply to an Ivy League school. There were other bright and accomplished individuals and I was fortunate to meet them. I had a mentor who encouraged me. In my class at Yale there were 1050 undergraduates of whom only 16 were African American.

Most of the kids at Stuyvesant High School were white. It’s a very good school and I was one of the first kids in NY to be bussed there. I began just a couple of years after Brown vs. Board of Education. Four of us were selected to attend in an experimental program.

We were shock troops to test the proposition that being placed in a predominantly white school would make a difference in being able to survive socially. It was not a program that lasted very long. NY found other ways through magnet schools and programs in integrating classrooms. Personally, I survived socially. In some respects, I was helped because I had polio when I was very young and was used to a level of social isolation. I grew up wearing braces and special shoes.

CG Those were the days of iron lungs.

TL I spent time in them.

CG People were not supposed to go to movies or beaches. I remember that from the 1950s before the Salk vaccine.

TL That’s right. I got polio just before the vaccine.

CG What was your home environment?

TL My mother was a nurse. Her career growth was limited because she didn’t have a college degree. When I was in junior high school she started night school at City College.

We graduated from college in the same year. She got her master’s degree before I got mine. Then she became a teacher in New York City.

This year she is 79. I have three step brothers. She remarried when I went away to school. I actually gave her away at the wedding.

I have always questioned one-way bussing programs. My own experience demonstrated social isolation in programs like Metco. The best and brightest from a neighborhood with predominantly ethnic characteristics are sent to primarily white schools. The exchange is not mutual. Students leave their communities early in the morning and return in the late afternoon. Over time they become disconnected from their home communities. Because they are on busses they do not get equal opportunity to interact with the social life of schools they are attending.

A number of parents of children involved with those programs tell me that they experience social isolation on behalf of their children. They hope that will be addressed when their children get into college. In a number of circumstances those parents push for their sons and daughters to enroll in historically black colleges. The intent is to reconnect with aspects of their culture. They have lost touch because of one-way exchange.

In my circumstance I learned a lot about New York’s progressive, primarily Jewish political culture. I became involved in the arts and politics. Through Stuyvesant and Junior High School I got involved with kids who went to the Village, listened to music, and visited The Museum of Modern Art. I went with them.

CG Were you accepted?

TL Yes. It continues to be easy to be accepted as a young person who is interested in art and culture. Crossing racial lines, you see that in hip hop, dance performances and concerts. Young people attending cultural events tend not to carry the same racial biases. One finds that in other aspects of society. It’s acknowledged that culture is a bridge that crosses race and class lines. I certainly found that to be the case. When we experienced music and museums we went as a group to The Met, MoMA, and Guggenheim. We were accepted and had a sense of community among ourselves. Most of us found that useful later on.

CG What attracted you to visual arts?

TL At Yale I studied photography with Walker Evans. He taught a class on advanced photographic technique. He commented on our work. I was doing a lot of documentary photography at the time. I didn’t realize who he was until halfway through the course. A roommate showed me a copy of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. That’s when I realized why he liked my work. We got along very well with each other. Prior to that in NY Abstract Expressionism was dominant in the art galleries. It was challenging the way that we look at the world. I saw the world in a very literal graphic sense.

CG A generation earlier you would have been a social realist.

TL I still like that work, particularly Reginald Marsh, and others of that school. I was familiar with a gritty, documentary view. My photography from that period reflected that. I was doing photo journalism for the high school paper. So when I went on to Yale I was used to photography as a documentary medium. When I saw Color Field Painting in museums, and Rothko’s work, then early Pop, it made me rethink how I looked at visual expression.

I was very much taken by the work of (Aaron) Siskind, (Harry) Callahan and Minor White. I had an affinity with Evans and Eugene Smith but I was fascinated by the more abstract work. It paralleled what painters were doing at that time. I had to reconceptualize how I looked at practically everything.; fashion, color, decorative perception, space. I went to museums to have the way that I looked at the world challenged. When you live in poverty and are surrounded by gritty circumstances you view the world in very literal sense. Looking at art in galleries and museums gave me a way of looking at a limited sense of how the world might be pictured.

CG Being selected as one of so few to have such unique education meant reinventing yourself. Your peers didn’t have that sharply demarcated social disparity. It made of you a young explorer pretty much on your own. That seems to have defined your persona as experiencing and embracing the unfamiliar. You appear to be comfortable with an outsider role and indeed thrive on it.

TL I spent a lot of time during school and after trying to define if there were any clear role models whose career paths I might emulate. Then, and to a large extent now, I have found very few African Americans with leadership roles in the arts, law, culture, finance, academic administration in any of the roles that I found interesting.

There were some artists who achieved a certain level of prominence then went on form their own dance companies. There were musicians who had prominent roles with record companies. Apart from a few examples I found few in professions that I had an interest in pursuing. I had no interest in being consigned to a place in this society that limited my opportunities. I realized early on that I didn’t have easily identified role models. I would have to do my own exploration and have always been comfortable with that because I’ve been curious and willing.

I have taken on diverse roles. I have had friends who were explorers. For one reason or another they have found it difficult to accept all of the responsibilities that sometimes come with being in that role. Of the group of African Americans who entered law school when I did a full third did not complete the program. They felt that the internal and external pressures were something that they didn’t want to have to deal with. When they envisioned themselves as the kind of people who were graduating from Yale Law School.

The same has been true for a number of settings I’ve worked in. There are a great many other people who could now be doing what I am but who opted for other career paths. When you are out ahead of expectations you quickly find a lack of support. There is not a lot of peer support because the circle tends to be small.

CG Do you sense having to reach a different level of accountability?

TL I stand out in lot of crowds which in itself imposes a higher level of accountability.

CG Can’t that uniqueness also work for you?

TL Many of the people I sit on boards with understand that the road I’ve traveled to get there was much more arduous. They respect that. They understand a credibility behind things that I might say. Sometimes the fact that I stand out because of a different background has worked for me because people understand that I had to work hard to get there. Some white people may have gone through the same experience.

CG What boards do you sit on?

TL The MFA currently I’m on leave from the ICA. The MFA board has some 33 members.

CG Why are you on leave from the ICA?

TL Because of the arm’s length relationship between the ICA and our BAC property as neighbors.

(The ICA vacated their Boylston Street property and built on the waterfront. The BAC now occupies that former property.)

CG You were formerly president of the ICA board.

TL Yes through calm as well as tumultuous times. I’m an overseer of the Peabody Essex Museum and serve on the education committees of Winterthur and Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston Salem.

CG That was your dissertation topic.

TL Yes they were very helpful for my research. My topic entailed narratives of collections of 19th century African American crafts including collectors and cultural life in black communities of that period. For individuals collecting material that is viewed as historical is there a bias that effectively expresses an interpretation of their views of what life was like at that time? Three different individuals collecting artifacts from the same time period compile collections that look different from each other. That stems from the fact that each collector focuses on a different aspect of that life.

That’s why the collections of museums differ. I was looking at what stories people believe should be told about life for black people both before and after slavery. The collections I dealt with were very interesting in that regard. They say a lot about how 20th century Americans look back at slavery and the roots of class distinctions.

I started work at Boston University in 1993 and earned my degree in 1999. That included eight courses then writing a dissertation. I already had a master’s degree in environmental design from Yale School of Architecture. From BU I hold a PhD in American and New England studies.

CG Did you really need that degree?

TL No, I shouldn’t say that actually. From 1983 to 1989 I was Dean of Graduate and Continuing Studies at MASS College of Art as well assistant to the President, Bill O’Neill. I was pretty sure I wanted to make a career in administration of higher education. For that, degrees in law and a master’s in architecture were viewed as insufficient. One needed a doctorate to attain the upper levels of higher education.

I attended Harvard Higher Education School for a year and a half but dropped out because of my work with the city. I had moved from MASS Art to a job in the administration of Mayor Ray Flynn. I started as director of the office of Jobs and Community Services. That entailed overseeing the city’s employment and training programs as well as community development activities. I had a budget of $19 million and a staff of 135. It was very interesting work.

The intensity of the work made it impossible to continue with school. Eventually I was able to work out a schedule. By 1992 I was able to enroll part time at BU to get course work done and write a dissertation. It struck me that a PhD would be useful but not essential. But I was interested in the material.

As a part of our effort to reduce gang violence in black and Latino communities I tried to identify some working-class role models. These individuals were not athletes, entertainers or clergy. The focus was on individuals who supported their families and left a legacy for communities from the 19th century to the present. Their efforts negated the stereotypes of gang violence as a vestige of slavery in America.

CG How do you equate being a gang member as a vestige of slavery?

TL There is an argument that gang culture exists because of class distinctions. Accordingly, gangs were the result or vestige of slavery. One had to have a political consciousness of slavery in order to understand why gang members banded together. They do things that are fundamentally antisocial to the predominantly white society.

The act of coming together with one’s brothers echoed the liberation efforts of black people going back to slavery. While that argument had some validity, it didn’t speak to the large number of people of color who had been able to sustain themselves and their families, for centuries, both within slavery and as free blacks of that period and after.

There had always been groups of artisans in Boston and elsewhere who made things that reference African roots. To what extent could we identity and use those artisans as role models for kids? We were presenting a more working-class alternative as role models for kids today. I set out to find who those people were. I wanted to identify the black silver smiths who worked with Paul Revere. We knew of them but haven’t been able to identify them by name. I wanted to know the black furniture makers who worked with the Seymours. I wanted to know who made furniture and craft in Baltimore, Charleston and New York in the 19th century. I knew they had to be there. Before welfare and government programs people had to work.

People of color survived as stevedores, blacksmiths and iron workers. I discovered that in parts of the south certain tribal members were favored in the slave trade because of their skill as iron workers. If you could acquire someone from the Benin culture it was likely that the individual would make a skilled worker. That was sought after in southern Virginia where there was a lot iron work.

CG The Benin people were slavers.

TL Yes but they were also enslaving some of their own people.

CG Have you traveled in Africa?

TL Not yet but I hope to. When we read Fredrick Law Olmstead’s diaries of traveling through the south and documenting slavery we learn about slavery as well as about Olmstead himself. He traveled before becoming well known as a landscape architect to study the horticulture and landscape. We learn a lot about him in the way that Henry Gates personalizes his (PBS) travel pieces. His series on Africa put a human face on the travel. It is a useful way to learn about the history and culture of Africa. It becomes more accessible and less like a text book.

CG Through the series it was fascinating to learn about high culture and libraries that existed during the era of the Renaissance in Europe.

Did you know and work with Elma Lewis and her school in Roxbury?

TL I have worked with Barry Gaither through the museum. (National Center of African American Artists) I’ve been a supporter and share the concerns of many people as to how the museum may be enlarged and more widely supported. Barry does extraordinary things there. Too many Bostonians do not appreciate his value.

CG Part of that is not having the budget for promotion and advertising. The media can’t cover the museum if there is no outreach.

TL There is truth to that but essentially Barry is a scholar. He’s a great teacher and public speaker. In eight years of city administration I learned that it is possible for people with limited resources to have a very large public presence. That occurs because they make the enlargement of their public presence a primary task. His mandate has been as scholar, archivist, curator and museum director. If you hear him speak it is extraordinary.

CG What is the legacy of Elma Lewis (1921-2004)? She struggled to overcome great adversity including vandalism and arson. There was a time why she was a vivid presence and now less so.

TL I wouldn’t say that. Elma made it possible for a lot of us to go on. There are a great many people who credit her for exposing them to the arts. That occurred through dance classes, Black Nativity, through Barry’s work, music classes and what have you. What has not happened has been a coalescing of that energy.

CG The school burned down and there was no money to rebuild it.

TL Many institutions comparable to the school have had similar tragedies and have rallied to recreate themselves. It will always be a mystery why that didn’t happen after the fire at the Elma Lewis School. I think of churches that burned in Roxbury where the congregations held together.

CG In addition to The Elma Lewis School, and National Center, the African American Artists in Residence Program at Northeastern University has also languished. Why have these initiatives struggled?

TL Boston’s black community (20% of its population) has had historical difficulty with self sufficiency of its cultural institutions.

CG Is that unique to Boston?

TL That’s partly because, unlike cities of comparable size, Boston’s black community is spread over a number of widely dispersed political jurisdictions. Often people in Cambridge don’t connect with people in Dorchester. People in Framingham don’t connect with people in Marlboro.

The result has been a failure to put together a critical mass of black leadership. You need that to sustain for the long haul the kinds of institutions we have been able to create but not support in perpetuity. Chicago has neighborhoods but is basically one Chicago. Boston has neighborhoods fragmented into smaller city jurisdictions that tend to separate people rather than bring them together.

Historically, Boston has been one of the most racially divided cities in America. One sees far more racial cohesion in Charleston or Savannah than one does in Boston. Savannah has a black mayor. In many cities of comparable size in the south, where one doesn’t expect black political leadership, it’s there. Boston continues as the capitol of the only major industrial state that has not sent a person of color to Congress.

(That changed with the election Ayanna Pressley to the current Congress.)

There has been an effort on the part of white society in Massachusetts to exclude African Americans from leadership roles.

(Edward William Brooke III was an American Republican politician. In 1966, he became the first African American, post Reconstruction, elected to the United States Senate. He represented Massachusetts in the Senate from 1967 to 1979. Deval Laurdine Patrick is an African American politician, civil rights lawyer, author, and businessman who served as the 71st governor of Massachusetts, from 2007 to 2015. He was first elected in 2006, succeeding Mitt Romney. The day after the New Hampshire Primary he suspended a 2020 campaign for President of the United States.)

Chicago is not a dominantly black city but it elected a black mayor as did Minneapolis.

(In 2018 there were about 32 black mayors of cities with populations of more than 40,000.)

This occurred in cities where black leadership came forward because the community was organized. The white community recognized that strength and was prepared to support it. That has not been the case in Boston. There has been racism in the schools, police and fire departments, the housing authority and other places. A group of whites have conspired to deny positions of black leadership. That exists because the black community continues to be divided within itself. Boston has suffered because of that.

CG Let’s return to the arts. Both the MFA and ICA have brick and mortar projects. The Rose Art Museum is also expanding. Harvard University Art Museums are in this mix. Trustees sit on multiple boards. During a building boom there is tension as institutions are attempting to pick the same pockets There are only so many potential donors and they are under enormous pressure. That puts the squeeze on the infrastructures of smaller urban arts organizations.

TL This doesn’t need to be. The economy of the region has generated enormous new wealth. There is enough to sustain these building projects. It will require building bridges to this new wealth. Many individuals and entrepreneurs are not yet actively engaged with institutions that need their resources.

If one were only to consider traditional pools of donors to culture there would indeed be problems. The new entrepreneurs emerging from high tech, dot coms, bio tech, development and other areas have barely been approached. I believe that in the next five to ten years the funds will be there. It already exists.

It will come from surprising sources when names and commitment are announced. Consider, for example, the Globe’s listings of top companies in the region. In terms of impact Fleet Bank and Gilette are near the top but not at the top of those lists.

If you look at the largest, most influential and who has the most employees, a number of companies on the Top 100 list didn’t even exist ten years ago. Who are the CEOs on that list and what is their age? Considering that emerging group and current cultural boards reveals that bridges are yet to be built.

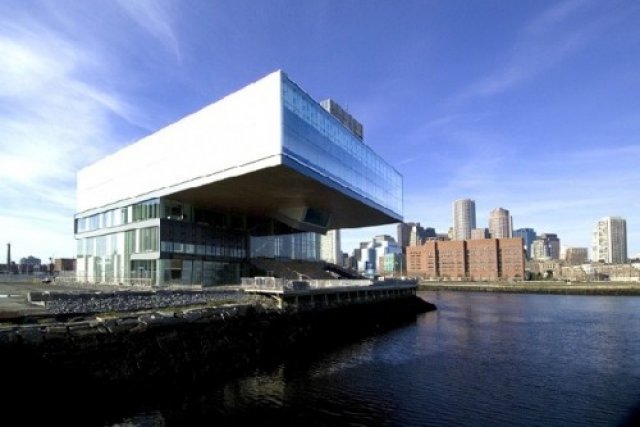

CG The ICA building on Boylston Street at a prime and accessible location has 6,000 square feet. It has struggles to survive and attracts some 25,000 annual visitors. The plan is to create a new home of some 60,000 square feet on the waterfront. Right now, the area is in early stages of development. Does expanding space by a factor of ten equate to a commensurate escalation of attendance. It is a given that contemporary art is a hard sell. How does the ICA address the challenging of erecting a building and expanding its audience?

(Designed with 65,000 square feet the building designed by Diller Scofidio & Renfro opened in December, 2006. While admired for its design the site is landlocked with no easy means of expansion. The ICA had also changed from a kunsthalle to a museum. That requires vital space to show and store a permanent collection. In 2018 it opened a seasonal annex across the harbor in East Boston. The ICA Watershed is located in the historic shipyard. A water shuttle connects the sites. The 2015 annual report stated visitation at 210,000. The 2018 annual report states total revenue at $18,492,377.)

TL The ICA audience, small as it is, has grown in the past couple of years. It will continue to do so by connecting to younger, curious entrepreneurs. Many of these individuals collect through Boston and New York galleries. They want a place to rally behind and that hasn’t happened for them at the MFA even though it has strengthened its contemporary programming.

The Rose does wonderful work as does the List at MIT. But they are academic programs and are not promoting to the emerging entrepreneurs and collectors. The ICA is creating a critical mass. Jill Medvedow has made it a priority to take what occurs in the building out into the community. The Vita Brevis program is a part of that.

(Summer, 2002, saw the third such event featuring the Emerald Necklace. It was presented by the Institute of Contemporary Art in partnership with The Boston Parks and Recreation Department, Art on the Emerald Necklace married the beauty and access of urban parks with the power of contemporary art which built and deepened our understanding of public life, public space, and creativity. Participating artists were: James Boorstein; Ann Carlson; Ellen Driscoll; Barnaby Evans; Sheila Kennedy, Franco Violich; Cornelia Parker; and Nari Ward. Michael Van Valkenburg, a landscape architect, created a photo essay for the catalogue of this exhibition which was published in 2001.)

That has provided a template of what contemporary art might do. It has been interesting to younger people. Nobody was aware that this kind of work was being done in Boston. As seen with artists she worked with along the Charles River. She was making a statement that contemporary art was not just a place where a few club members could get together and hold private meetings. Regarding the meaning of art, she’s taking it to the streets. And doing it in ways that challenge perceptions of how we see the world. This is occurring in the same way as when I saw Rothko’s work at MoMA in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. She is committed to building an audience by making public art and contemporary art more accessible.

CG Is there foot traffic along the waterfront? If it’s a struggle to get 25,000 annual visitors to Boylston Street how are you going to lure them to the waterfront?

TL People passing by (Boylston Street) have no sense that it is a museum. There’s no street presence.

CG That’s what Milena (Kalinovska) told me. She discussed plans for signage and marketing but the board shot it down.

TL I think you are very wrong about that. There were a lot of us on the board that felt that we needed much more of a public presence on Boylston Street. We needed to do more with windows and lighting. We needed to repaint the exterior sign. These were never Milena’s priorities. She was more interested in being a curator. She was often uncomfortable dealing with the Boston media. As well as with marketing and public relations. She was a curator who brought in a number of shows which were interesting sometimes but quite inaccessible to a more general public.

CG Are the shows more accessible now? (Under Medvedow)

TL I think they are because they are presented in ways that enable an audience to connect and relate to them in a more visceral way. The Sabbath Day Lake (Shakers) show for example, touched a lot of people emotionally.

CG That was indeed an exceptional experience of collaborations of outstanding artists in residence with the Shakers. They made work as well as participated in the daily life of the community.

TL The recent Steam Roller (Cornelia Parker) who was reviewed in the Wall Street Journal. Since Jill had been here I can think of several shows that are memorable in a positive way. Not everyone is going to like everything but Jill has made a substantial effort to make shows more accessible. On any given day there may not be a lot of people in the galleries but you measure success by more than numbers.

I am partly measuring success in terms of audience but I am also measuring it by the institutions ability to impact public consciousness of public art. The mere fact that the ICA was designated to move to the waterfront, and this mayor (Thomas Menino) has endorsed that, as well as developers. They believe that having contemporary art on the waterfront is an anchor to draw other cultural institutions into that area. That’s important to this city. Tell me the last time that has happened? Tell me when any other cultural institution has had that impact? Arguably, one might talk about the Boston Ballet opening its Graham Gund designed building in the South End. But it has been a long time since we’ve seen any cultural institution’s development of a parcel that has an impact in terms of raising public consciousness of the work of that institution.

The ICA is moving ahead on schedule. (The building designed by Elizabeth Diller and Richard Scofidio opened in December, 2006.)

CG How do you evaluate the performance of Mevedow in terms of moving this forward. David Ross stabilized the ICA during a difficult time. While successful on many levels he was never able to initiate a new structure, which was also true for Milena Kalinovska. What’s different now?

TL I have a bias as I’m a big fan of Jill. The energy she had brought and commitment to making contemporary art accessible have worked to the advantage of the ICA. She has brought new vitality to the board and they have considerably helped with fund raising. More money has been raised in the past year and a half than in the entire history of the ICA. I say that as a former board chairman.

At this moment they are engaged more in a public discourse about culture than any other Boston institution other than the MFA. And yet they have an annual budget of only a couple of million dollars. Compared to which the MFA has a budget of $90 million. The MFA widely advertises while the ICA has no such resources. Despite that, if you ask people to name the top cultural institutions in Boston they are up there with the MFA, BSO, and Boston Ballet.

CG Should the ICA, which was founded as a kunsthalle, finally start to collect when they have a new building?

TL In my view they should have a formal working relationship with the MFA. They should be the non collecting affiliate of the MFA.

(That came close to happening when Thomas Messer was director of the ICA. The Institute was housed on the second floor of the Museum School. The plan was to merge the ICA as a department of the MFA with Messer as its curator. He began to advise on some notable acquisitions. That ended when Perry T. Rathbone became the MFA director in 1955. He viewed modern and contemporary art as a part of his portfolio. Rathbone appointed Kenworth Moffett and established a 20th Century department before he left in 1972.)

We might have something like the relationship between MoMA and PS1 in New York. I have favored that for about ten years. When I headed the board, and there was talk of a new building, I suggested the site across Huntington Avenue from the MFA. The Wentworth Institute of Technology playing fields have now been created on that site. There might be a symbiotic relationship with the MFA. I don’t think that collecting will help the ICA. When you collect, what is shown always has to be contextualized by what is collected. You may say that it’s unrelated but someone will always ask questions when the institution does something weird and experimental. How it related to your core mission as expressed by what is collected.

(The potential synergy that Landsmark expressed in 2000 never happened. Palpable tension between Medvdow and former MFA director, Malcolm Rogers, was widely reported. They were competing for funding from a limited pool of donors. The ICA did start to collect and now has the challenge of finding space to display and store a growing collection. The ICA has rapidly outgrown its relatively small, questionably designed and unpragmatic building.)

CG A collection is collateral as with time it accrues values. It’s a non liquid asset that many institutions attempt to monetize. It’s a bargaining chip when negotiating loans for exhibitions. It’s another reason to visit a 60,000 square foot museum on the waterfront.

TL There are other ways of dealing with that. Suppose that the ICA were perceived as a portal to existing contemporary art collections. That includes Harvard, MFA, the Rose and private collections. Consider that some portion of ICA shows were drawn from those collections which cannot be shown in their entirety. Doing that in a way that would collateralize their role as a place where one accessed learning and discussion around contemporary art.

You see the down side and I have an argument with people who favor collecting, and they get exasperated. After not much time the burden of conserving, insuring, storing and handling a growing collection takes over from the work, particularly of contemporary curators, have to do in order to remain agile. Curators have to be able to respond quickly to a world where culture is changing rapidly. I think there are some places that have to collect and they are called museums.

CG You reference that MFA is one of those places for modern and contemporary art. We can agree that of major, encyclopedic museums it has performed poorly.

TL At the last (MFA) board meeting we were presented a policy statement on contemporary art drafted by Steve Grossman and a group of other people. The expectation at this time is that the commitment will be ratcheted up significantly and should show up in this upcoming budget cycle. I don’t, however, know what that will look like. I know that Malcolm (Rogers) is fundamentally committed to increasing the level of presence that the MFA has around contemporary art, in part because of the synergy that exists between the school and the museum. He’s sensitive to the long-standing criticism that over the years the MFA has dropped the ball on contemporary art.

CG For about a century.

TL The MFA has taken on more challenging projects. In Boston, and I don’t mean this in defense of the MFA, the culture of the city has been apathetic to exposure and collecting of contemporary art. This is a different environment than that of other major American cities. Most other cities, however, don’t have the ICA, List at MIT, The Rose Art Museum, the galleries at MASS College of Art, Boston University and Boston College, Wellesley. There are Newbury Street Galleries, Mobius, the galleries on Fort Point and elsewhere. Few other cities have that range of places that show contemporary art.

(There are the Danforth Museum, DeCordova Museum, Fitchburg Art Museum, Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton also numerous school and college galleries in the Boston area including The Museum School, New England School of Art and Design/ Suffolk University, Art Institute of Boston, Emerson College, U Mass Boston, Newton Arts Center and others.)

In some of its mistakes the MFA is much more like the Met which similarly has not shown a great commitment to contemporary art. The context has been for doing more traditional things. With more experimental institutions doing more cutting-edge work.

I recall show at MASS College of Art and performance pieces that came out of their SIN department. They were cutting edge works. It’s not as though the people of Boston have been unwilling to look at experimental art. The more progressive institutions have taken the heat off of the MFA in terms of what its internal policies could and should have been. The MFA is coming to embrace contemporary art in a serious way but much too late. Contemporary art continues to be produced (in Boston) and I think we are going to see that emerging more now.

CG The current MFA curator, Cheryl Brutvan, is not the right person to be doing that.

(She joined the museum in 1998 and was largely regarded as doing the bidding of Malcolm Rogers. The position had been open for two years when Trevor Fairbrother departed. Brutvan left in 2008. Edward Saywell was appointed director of the MFA’s West Wing where he reinstalled the contemporary art collection. Under Rogers there was transition and change in the art world when Brutvan was hired. Carl Belz had just stepped down as director of Brandeis’ Rose Art Museum to be replaced by Joseph Ketner (both now deceased), Adam Weinberg became director of Phillips Academy’s Addison Gallery. He is now director of the Whitney Museum of American Art. MIT List Visual Art Center director Katy Kline left to be replaced by Jane Farver (deceased), Linda Nordan became contemporary art curator at the Harvard Art Museums, and Jessica Morgan became the Worcester Art Museum’s contemporary curator, only to quickly jump to the ICA. Brutvan compared poorly to these individuals. Matthew Teitelbaum, director of the MFA since 2015, formerly was an ICA curator. With some speedbumps he is steering the museum in a new direction.)

TL That’s your judgment to make (Brutvan).

CG The List (under director Jane Farver and curator Bill Arning) is showing what’s happening today. The ICA is several years behind and the MFA is focused on what developed a generation ago. That is the time line of contemporary art in Boston as I see it. The List with it challenging programming is as up to speed as possible. They have a tradition of that.

(Wayne Andersen was director of MIT’s Hayden Gallery. Kathy Halbreich collaborated in bringing the MIT List Visual Arts Center to an I.M. Pei designed building shared with The Media Lab which was founded by Nicholas Negroponte. Halbreich left to head the Walker Art Center. Farver came from the Queens Museum following Katy Kline. She engaged me in a regular dialogue about exhibitions and concepts that had a formidable degree of difficulty. In the true sense of MIT the programming was probing, brilliant and experimental. She died suddenly in 2015 while installing work by Joan Jonas in the American pavilion of the Venice Biennale. Jane was a colleague and friend. Bill Arning who was a List curator under Farver was inventive and notable for knowing more Boston artists than any other art world professional other than James Manning now with the gallery of Emerson College.)

The ICA is currently showing Fishli and Weiss which is more like what was topical several years ago.

TL I won’t challenge you on this. You’re the critic.

CG Last year the Brooklyn Museum showed Sensation work from London’s Saatchi Collection. There was the reaction of Mayor Giuliani who never visited the exhibition but attempted to shut it down. Of course, that made it the show that everyone wanted to see. The response of the art world was more apathetic. Much of the work had already been shown in New York.

TL You have to ask what roles particular institutions ought to play in a city which has a number of venues to see work. You can’t ask any single institution, be it the MFA or ICA, to carry the load. For me the issues are less that the MFA has failed to collect or show what it could or should have, but more importantly, that it failed to connect with other institutions in ways that supported their activities.

If they had done for Mobius, for example what they did for Gaither’s National Center for African American Artists that would have created an umbrella for creative activity. That would have created collecting activity where the burden wouldn’t be entirely on them (MFA). But they would be credible because they would be supporting people in venues where it is appropriate for those artists to explore their work.

(The Mobius Artists Group is an interdisciplinary group of artists, founded in 1977 by Marilyn Arsem. Mobius has produced hundreds of original works which have received favorable reviews in Boston, nationally and internationally. Works have been presented throughout the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia. Artist-exchange projects bring collaborator together including from Macedonia, Croatia, Poland, and Taiwan.)

CG Consider the recent ICA show Boston Collects. The selection including work by Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois, Gerhard Richter, Kara Walker had few surprises. Other than loans from Ken Freed there was little or no risk taking in the selection. Great collections are not assembled by rich people with advisors buying work from the secondary market.

TL When there are long standing venues like the List and Mobius often what needs to happen is for larger institutions, through appropriate partnerships, to encourage individuals to collect with the understanding that these objects eventually will come to museums. The museum, for its part, has to demonstrate that it is committed to showing that kind of work. That includes exhibitions, programming and everything that goes with that. They need to be showing contemporary art in a way that makes it accessible to people.

But the museum itself doesn’t have to hold all of it in their own holdings throughout that whole period. That’s not necessary if it has done the right work with collectors. I don’t think the MFA has done that with collectors of contemporary art.

The good quote is that major institutions have a responsibility to establish creative partnerships with cutting edge and risk-taking institutions in ways that support the work of those progressive institutions. This moves forward with the understanding that some of that risky work may ultimately end up in the museum. But it is not necessarily the responsibility of the museum to do long term holding from the very beginning. This is the same approach of large companies that create or support independent ventures, R&D, through related or supported companies. The same thing has to happen with cultural institutions. The MFA has to find ways to have creative support for other institutions doing progressive work. It must support contemporary art in the same manner that, at a threshold level, it has supported Barry Gaither’s work at the National Center.

CG In years of following and reporting on the ICA it has often functioned as a matrix for the social activities of the trustees and elite group of well-connected patrons. It was noted for throwing fundraisers that were more inventive and creative than actual exhibition programming. This social activity never seemed to involve or embrace artists who are the foot soldiers of the arts community.

(Milena Kalinovska offered an oddly skewed program of exhibitions. There was an emphasis on aspects of feminism from historical surveys (Inside the Visible curated by Catherine de Zeghe, 1996) to solo exhibitions. Often, they were based on her connections from years in London and Europe for example Rachel Whiteread, Carol Rama, and Marlene Dumas. These exhibitions were well reviewed but failed to attract significant audiences. She initiated populist shows like photographers Annie Leibovitz and Bill Wegman, Elvis and Marilyn, Dress Codes (exploring gender issues) and Malcolm X. The exhibition New Histories explored African American art. These efforts targeted specific audiences but did not develop into a consistent base for the ICA. Part of that, as Landsmark commented, may have been a lack of understanding and focus on media and marketing. That raises the issue of a museum director as chief curator or administrator and fundraiser. The more effective strategy if to hire qualified curators and support their work.)

TL The work that Jill (Medvedow) has done for the ICA in a number of Boston communities has been a significant step forward. It has taken contemporary art out of the galleries and put it into communities where it becomes accessible. What other museum has done that? To what extent do artists working in the South End connect with artists and universities in Cambridge? There are ways to make that happen.