Richard Giarusso and the Aoede Consort Triumph in Schütz'

Superb performance of Heinrich Schütz's choral masterpiece

By: Michael Miller - Feb 21, 2007

The multi-talented Richard Giarusso continues to explore single-mindedly one vitally important and fascinating area in music—the relationship between music and text. Last summer he offered an original and moving interpretation on Franz Schubert's Schwanengesang, and, before he goes on to Die Winterreise this coming summer, he has given us an all-too-rare opportunity to hear perhaps the most sophisticated and eloquent fusion of text and music before Schubert, Heinrich Schütz's Musikalische Exequien, a Lutheran funeral Mass to German texts, which Schütz wrote for the funeral of Prince Heinrich Posthumus Reuss, of the ruling family of the region in which Schütz was born. The eleven participating singers of the Aoede Consort (based in Troy, New York) and Giarusso's direction were superb, but first, I'd like to provide some background.

Heinrich Schütz (Köstritz near Gera 1585-Dresden 1672), unquestionably the greatest German composer of the seventeenth century, was born into a prominent bourgeois family which had settled in this part of Saxony over a century before. His father was town clerk in the Reuss seat, Gera, but later moved to nearby Köstritz to take over his father Christoph's inn, "Zum goldenen Kranich." Christoph later acquired more inns and moved to Weissenfels, where he became burgomaster. The children of this prosperous family received solid religious and liberal educations. Two of Heinrich's brothers studied law and became prominent jurists, and their father intended the same profession for him as well. As apt a scholar of languages as he was, Heinrich also showed an early gift for music. The Landgrave Moritz of Hessen-Kassel, who was a distinguished musical amateur, heard the boy sing while he was staying at the inn in 1598, and was so impressed that he invited him to come with him to his court in Kassel, where he would attend the Collegium Mauritianum, a first-rate school founded for the local nobles. Christoph resisted and continued to resist for some time. The next year, however, he brought Heinrich to the court, where he had an opportunity to excel at Greek, Latin, and French, as well as music. In 1608, Heinrich went to the University of Marburg to continue his classical and legal studies, but the Margrave intervened once again and persuaded him to leave the university and go to Venice to study with Giovanni Gabrieli (Venice ca. 1554–7 – 1612). After some initial difficulties he became Gabrieli's star pupil. A year after Gabrieli's death he returned to the Margrave's court as a musician, while his family continued to discourage him from a professional interest in music. He was about to give in to their unrelented pressure and return to the law, when the Elector Johann Georg I of Saxony invited him to Dresden. In 1615 the Elector gave such support to Heinrich's musical vocation, that his family finally relented, and he settled into the court at Dresden, where he remained for the rest of his life, appointed court Kapellmeister in 1621.

I have outlined Schütz's early life in some detail to show what a profoundly educated man he was, especially in Latin and Greek, which gave him the key to his great achievements in bringing music and the German language together, adapting the choral style he had learned from Gabrieli to his native tongue. Moreover, as Richard Giarusso pointed out in his introductory talk, Schütz is not as well known as he should be, and every music-lover is the poorer without knowing his music or his life. This, if it does not provide the iconic myths by which most of us know Mozart, Beethoven, et. al., will at least give an impression of who Schütz was and how his character, time, and place moulded his music.

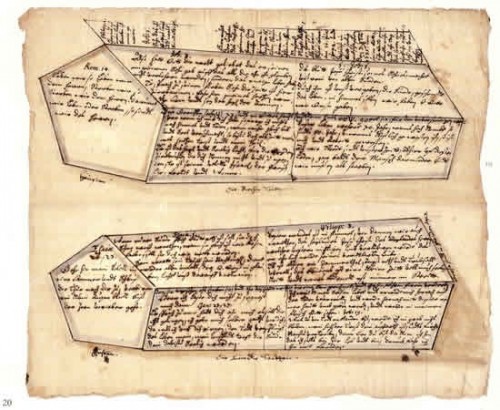

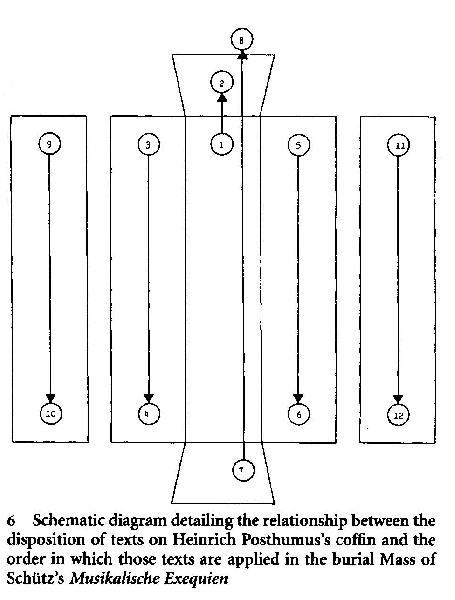

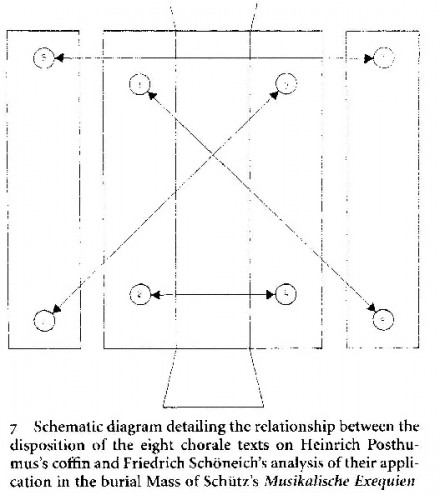

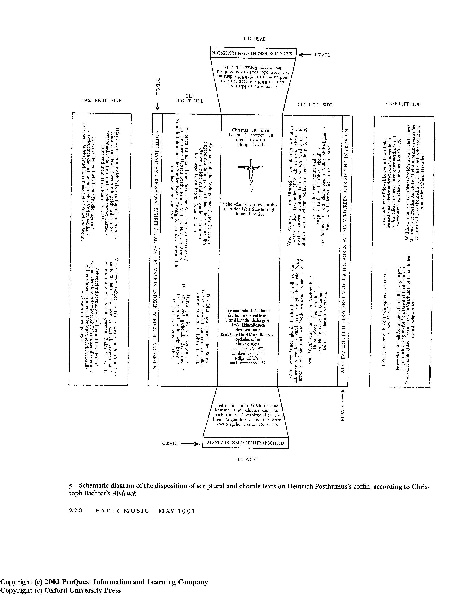

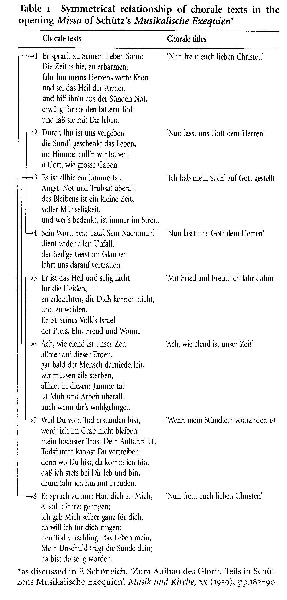

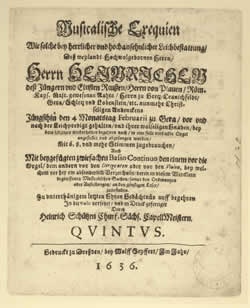

Schütz and his deceased patron Reuss had known each other for some twenty years before Reuss' death in 1635. Schütz showed considerable devotion to the ruling family of his home town, and his relations with Heinrich appear to have been closer than that. Schütz's long, formal introductory text to the published score of the Exequien, shows his respect and warm feelings. Heinrich was himself a deeply learned man and an active patron of the arts, a humanist-aristocrat after the model of Willibald Pirckheimer (1470-1530), Dürer's friend and patron. He was also a responsible and competent prince, who worked systematically and effectively to restore his principality's shaky finances and shelter it from the violence of the Thirty Years' War. The Schütz's and people like them can only have felt gratitude for his efforts. Like the good Lutheran humanist that he was, Heinrich began to prepare seriously for death as his grand climacteric approached. Over the next year he made detailed preparations for his funeral. He commissioned a copper coffin to be made in secret, decorated with biblical and choral texts of his own choosing and arrangement, which reflected the Lutheran theology of death. (See the accompanying illustrations.) These texts, in fact, were the very ones Schütz used for the first section of his tripartite Exequien, the "concerto in the form of a German funeral Mass." Over the past fifty years several musicologists have established the relationship between the complex symmetrical structure of the text and music with the arrangement of the texts on Reuss' coffin. [See G.S. Johnston: "Textual Symmetrics and the Origins of Heinrich Schütz's Musikalische Exequien," Early Music, xix (1991), 213–25.) This means that the deceased prince had some influence on the form of the Exequien, which was technically commissioned by his widow. Since the collection of texts was the confessional testament of this extraordinary prince, Schütz had exemplary material for his insights into the relationship of music and the German language. Indeed, it is remarkable how expressive and complex Schütz' music can be without disturbing the natural rhythms of German speech.

While the first movement was written for a single six-part chorus, alternating with duets and trios by the soloists, the second movement is a motet for double chorus ("Herr, wenn ich Dich nur habe/Lord, if I have none other than You") on one of the texts for the funerary sermon at Reuss's funeral. The third movement, a setting of the "Song of Simeon" from the Gospel of Luke, is a "Concerto for two choruses in which each chorus has its own words" with a third group from the second chorus singing "Selig sind die Toten/Blessed are the dead" from the Beatitudes. This third group is intended to sing from a remote location, an effect Schütz's teacher Gabrieli often exploited in San Marco. The first section would have functioned as an Introit or Missa Brevis, while the second and third would have followed the sermon.

While Schütz's remains something of a mystery to modern audiences in spite of the vitality of the early music movement, I have never seen an audience walk away bored or unaffected by the music. Mr. Giarusso and the Aoede Consort offered a remarkably polished fully realized performance, compromised only by the indisposition of one singer. They quite properly adhered to Schütz's indication in his introduction that there should only be twelve singers. The acoustic of Williams' Memorial Chapel is probably a bit less reverberant than the Johanniskirche in Gera (destroyed by fire in 1780), where Heinrich's funeral took place, but this did not impair the effect of the solo parts weaving seamlessly in and out of the tutti—perfectly managed by Mr. Giarusso. A larger chorus would have ruined this. Again in the last movement the isolated trio (two seraphim and the anima beata) could not approach the ethereal quality achievable in in an acoustic resembling San Marco, but the point came across well enough. The singers of the aoede ensemble are superb, both as a group and as soloists. I especially enjoyed the beautiful production and phrasing of sopranos Katherine Dain and Alison Mondel and contralto Mary Abba-Gleason, not to slight the fine singing of the male soloists.

The first part of the program, which consisted of three motets from Schütz's Geistliche Chormusik (1648) and two by his great predecessor Orlando di Lasso (1532-1611). Mr. Giarusso's slightly deliberate tempo and long, arching phrases served this music as well as his penetrating understanding of the Musikalische Exequien.

Williamstown Early Music has shown once again what an asset it is to the Northern Berkshires.

Web: http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

email: michaeljames48@gmail.com