When by Ledelle Moe

Massive Sculptures by South African Artist at MASS MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 21, 2020

The dim but evocative lighting in the vast space of Mass MoCa’s Building Five creates drama: there is daunting pause when you enter and then comes the gut-wrenching intensity of the monumental, figurative sculptures of South African artist Ledelle Moe.

Curated by Susan Cross, the powerful special exhibition When will be on view at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) in North Adams through September 5. The enormous gallery, the largest in North America, sets a career defining challenge for artists. Given the annual rotation in the space since the museum opened in 1999, there have been hits and misses. There is little doubt that Moe’s installation is on the short list: it is one of most astonishing projects the gallery has hosted.

That critical assessment is underscored by how the artist has triumphantly solved a seemingly impossible conundrum. The work is fresh, innovative, and contemporary — yet deeply rooted in a primal humanism that courses through the millennia of every continent and culture.

Being both then and now, here and there, conflates as When.

The generous space surrounding Ledelle Moe’s several monumentally scaled works lends the show the ersatz solemnity of architectonic, funerary sculptures. The intensity of impact is iconic: it resonates with encountering the Neolithic “Venus of Willendorf” in Vienna, the epic, enigmatic moai of Easter Island, or huge Olmec heads of pre-Columbian culture.

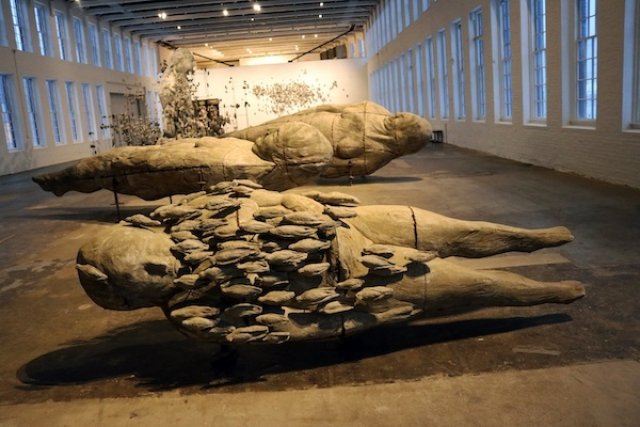

The later references come to mind when you interact with a pair of huge heads (Memorial [Collapse], 2005) set on their sides. They serve as a prelude, guardians of the gate as we move on to horizontal figures that are supported by metal armatures hovering off the ground. The figures, abstract rather than specific, proffer compact forms, with arms tight at the sides, legs straight and together. They appear as though laid out for burial.

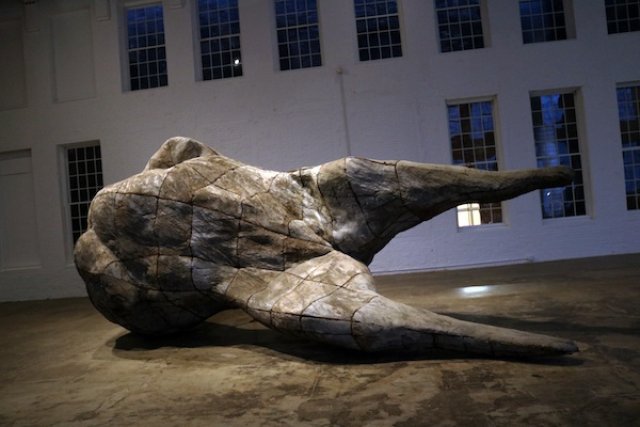

There are also splayed out anthropomorphic sculptures. Perspective morphs what we make of what we are seeing: the shapes evoke a conch shell, bird or animal forms. Gazing into the crotch reveals undefined gender. One figure is covered by resting birds. A kneeling woman ([Remain], 2019) is surrounded by an armature supporting small forms that are left to our imagination to identify. The giant enigmatic figures generate wonder.

It is instinctive if sometimes reductive to want to know what a work of art means. Is it a mandate for the critic to teach and explain? There is enough that is representational about Moe’s oeuvre to invite speculation about how to interpret these figures. Reviews quote the artist on specifics, where there is talk about the sudden loss of a mother and grandmother. Looking at Moe’s art from that point of view — personal loss — has its insights.

But such easy and ready answers trump the more productive, and valuable, process of posing questions. Consider that the greatest and most compelling works of art demand patience; they are slow to reveal their metaphors and mysteries. There is much about Moe’s work that I prefer not to know: nightshade is more revelatory than daylight. The wise muse hovers in the dark.

My preferred interpretative approach is not to attempt a deconstruction. It’s better to reflect on response to the work itself. What is its itness or thingness? Try to interact with the work itself. How, in the context of contemporary art, do we make sense of these sculptural titans? What is their mysterious power, their links with humanity and universality? How do we grapple with them: are they Freudian projections of helplessness or archetypes from a Jungian collective unconsciousness? In what ways does the artist connect with our shared spirit world? I suggest that she is evoking our deepest dreams of mortality — and beyond.

Bounce Moe’s work off the padded banks of art history and you have a game of billiards. There are numerous paradigms and analogies. The rough surfaces and scored, scratchy textures recall the unfinished slaves from the Julius II tomb project of Michelangelo in the Accademia Gallery. The Neolithic goddess imagery channels similar themes in the work of Ana Mendieta. There are connections to the art brut of Dubuffet. Rough, deliberate primitivism evokes the quirky textures of Giacometti’s sculpture. The latter connection is strongest in a selection of scratchy, nervous, staccato drawings of heads, horses, and winged figures. They display the unique qualities of drawings made by sculptors: the concerns with form, and how imagery sits on a page.

The drawings, including etchings and sketchbooks, are displayed flat in vitrines. There are several of these in the balcony area and they assist viewers in understanding the work. The form of display may be casual, but they are more than specimens and footnotes — the drawings are works on their own terms.

Another sidebar to Moe’s huge objects is a wall of numerous, fist-sized heads. This sprawling and irregular relief (Congregation, 2006) was created over years in multiple locations. The artist mixed local soil and sand with concrete so that each would absorb the site’s specific duende. The generic heads suggest some sort of dialogue (or chatter ) is taking place, perhaps in a market or a forum. Of course, we have to imagine the conversation. For the artist, the faces represent memories of people she encountered in her travels.

Let’s conclude with a sense of awe. How does the artist, apparently working without assistants, construct sculptures that weigh 2,000 pounds? The figures are constructed out of sections of welded metal and mesh. Over this is slathered cement which is then patinated with paint. The sculptor miraculously refines the dull, unaesthetic aspect of cement. There have been counterintuitive uses of concrete in architecture from Le Corbusier and Paul Rudolph to Tadeo Ando. Unlike stone, marble, or bronze, there is nothing inherently beautiful about cement.

As material, concrete is cheap and generic. Its aesthetic value derives from the forms it is poured into or, in Moe’s practice, the complex armature that supports the surface. Cement is vulnerable to decay — it is less than permanent. Moe appears to embrace its ephemerality. Her work has been fashioned for archaeological investigation: it is an ironic strategy that celebrates, rather than undermines, notions of time, mortality, and the beauty of ruins.

Response from the artist.

Dear Charles Giuliano, thank you for such a provocative insightful and generous article. I would like to clarify, that although I make all the work myself ( ie I do not use fabricators), I have over the years worked with wonderful assistants. These young artists have been an essential part of helping with the lifting, holding, meshing and mixing of materials to make the work happen. Core assistants have been Morgan Frailey, May Wilson, Milandi Coetzer, Abongile Ngqunge, and Samantha Pasapane. For many years my partner, friend and artist, Jesse Burrowes, was an essential part of many of the fabrication of elements of the works and my friends and fellow artists Siemon Allen and Kendall Buster have been key to problem solving elements of the works.

Creating sculpture, for me, is both a solitary and collective endeavor — one that brings people together in incredibly rewarding ways. Thank you for allowing me the time to contribute this to your rich and insightful article. Ledelle Moe

This article is reposted from Boston's Arts Fuse.

Review of When by Astrid Hiemer.