Coronation of Poppea's Trip to Venice

Monteverdi's Last Opera Triumphs

By: Susan Hall - Feb 22, 2017

Concerto Italiano

L'Incoronazione Di Poppea

Rinaldo Alessandrini, Conductor and Harpsichord

L'Incoronazione di Poppea

Miah Persson, Soprano (Fortuna, Poppea)

Leonardo Cortellazzi, Tenor (Nerone)

Roberta Invernizzi, Soprano (Ottavia)

Sara Mingardo, Contralto (Ottone)

Salvo Vitale, Bass (Seneca, Tribuno 1)

Francesca Cassinari, Soprano (Virtù, Valletto)

Aurelio Schiavoni, Countertenor (Arnalta, Familiare 1)

Monica Piccinini, Soprano (Drusilla)

Anna Simboli, Soprano (Amore, Damigella)

Valerio Contaldo, Tenor (Soldato 1, Familiare 2, Lucano,

Console 1), Raffaele Giordani, Tenor (Soldato 2, Nutrice, Console 2)Mauro Borgioni, Baritone (Mercurio, Familiare 3, Tribuno 2, Liberto)

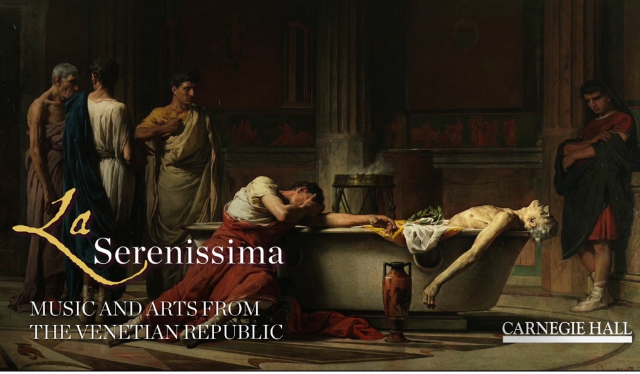

La Serenissma

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

February 21, 2017

Joining words to music in the secular world was a new idea when Monteverdi composed his last opera, L'Incoronazione di Poppea. The idea that emotion and character could be expressed in music was also new. Monteverdi’s compositions are full of glorious music and his understanding of the complicated human soul is rich. Intrigue of course abounds.

The characters Fortune, Virtue and Love argue at the beginning of L'Incoronazione di Poppea. Who is most important in world affairs? Love wins the argument. This becomes an opera about love in many forms.

Let’s take pure love first. Drusilla, handmaiden to Poppea, the Empress-in-waiting, is truly in love with Ottone. This pure love is rewarded in the end by a reprieve from the Emperor. Ottone is in love with Poppea, yet grateful for Drusilla’s passion.

Sara Mingardo, a true contralto, was magnificent as Ottone, mourning her lost love, and confused by her last mission, to kill her love Poppea on orders from the current Empress, Octavia. Hers was one of the most exciting voices on stage.

Poppea’s love for the Emperor is heavily tinged with her lust for power and the crown. She knows how to play the weak and vain Emperor who famously fiddled while Rome burned.

Recitative is interwoven with brief solos. Miah Persson, in a convincing performance as Poppea, induces Nero to spend the night with her, and then begs him to return. The natural ebb and flow of the words follows in music.

Nero breaks in passionately, if briefly, to declaim his love for Poppea. As Leonardo Cortellazzi sings the Emperor Nero, love seems most often lust. We are wrapped in a circle of obsession, a perfect circle for an opera.

Clever Poppea of course succeeds in disposing of Nero’s wife Octavia, as she reveals Octavia's plot to kill none other than Poppea. Miah Persson tantalizes as Poppea, not only in her lush voice, but in her complex performance and her swirling reds and muted black silks.

Counter tenor Aurelio Schiavoni in multiple roles displayed an extraordinary purity and beauty in his head voice.

Monteverdi had his own intrigues. Appointed as music master at Mantova, the duke failed to pay his salary and so he moved on to Venice, where at 45 he became the music master at St. Mark’s. He was among the first composers to write effects like the tremulo for the violins. These were deliciously present in the performance of the Concerto Italiano.

The tonal and formal unity of the opera was made clear in the instruments and the conducting by Rinaldo Alessandrini. He is an expert in the baroque period and Monteverdi. He used a scaled down chamber orchestra to further reveal the sung words, which are clearly of most importance to the composer.

The rhythm of the opera flows from recitative, or words spoken to music, to vocal music that is more melodic than recitative but less formal than an aria and then to spoken words. In this production all the forms are seamless and yet their variety makes compelling listening.

Nero argues that force is law in peace and the sword in war. Seneca, the Stoic, sung in a stentorian bass by Salvo Vitale, says that all we need is reason. As passions intensify, Nero and Seneca's dialogue alternates in the ever more rapid "agitated style" developed by Monteverdi. Effects such as rapidly repeated notes and extended trills are symbols of bellicose agitation or anger.

While Octavia, Nero’s wife, is portrayed in most ancient literature as a good woman, the librettist here has imposed qualities of Nero’s wicked mother on her. Roberta Invernizzi was particularly thrilling at her nastiest.

Glorying in the music, it is easy to slow it down and revel. A bit of briskness might have brought the edge of the story into sharper focus. Yet the non-judgmental angle of the composer on even the most deeply-flawed characters makes a close listen rewarding.

This opera, designed for a small theater, did not seem engulfed by Stern Hall, because the centrally positioned chamber instruments and the powerful singers and story filled every nook and cranny of Carnegie. Being in Venice at its height for two weeks in La Serenissma has been a special treat designed by Carnegie, which extends listening in such pleasureful and often unusual ways.