Dana C. Chandler, Jr. Two

Founding AAMARP at Northeastern University

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 24, 2015

Charles Giuliano How did African American Master Artist-in-Residence Program (AAMARP) start?

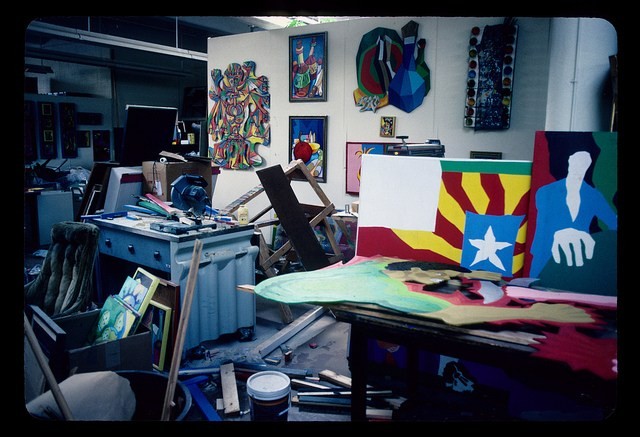

Dana C. Chandler, Jr. In 1973 my studio at 15 West Brookline Street in the South End was destroyed. I went on vacation and when I was away someone broke in and stole my artwork and everything they wanted. They scattered my works around the neighborhood and hung some of my paintings on the walls of the playground. They ripped up the paintings and I found pieces of them scattered all around.

The work at that time was very pointed and sharp. I don't know how people knew that I was on vacation. My suspicion was that it was part of all the foolishness that was going on at that time related to black people. Can I prove any of it? No.

CG Who do you suspect for doing this? Was it white people? Was it an act of vengeance.? I am trying to get an understanding.

DC If you're asking me if I feel that's what was happening the answer would be yes. Can I prove it? No. Did some other folks from the community run through there too? Yes. They left the doors open. So when I walked in I had to kick some people from the neighborhood out of the studio. They were stealing my artwork. The doors to my studio were wide open.

Somebody turned the water on in the basement which was flooded. So that destroyed all of the artwork I had stored there.

CG Can you quantify what was lost?

DC I would say a good 80% of what I did.

CG Jesus.

DC That's what I said and a few other things believe me. That was 1973. A couple of weeks later somebody came by and burned the building down.

It was a very unpleasant experience. On the one level. On another level it was a great learning experience. After that I was no longer subject to the idea that art was immortal. Nothing is immortal. Anybody's stuff can disappear at any point.

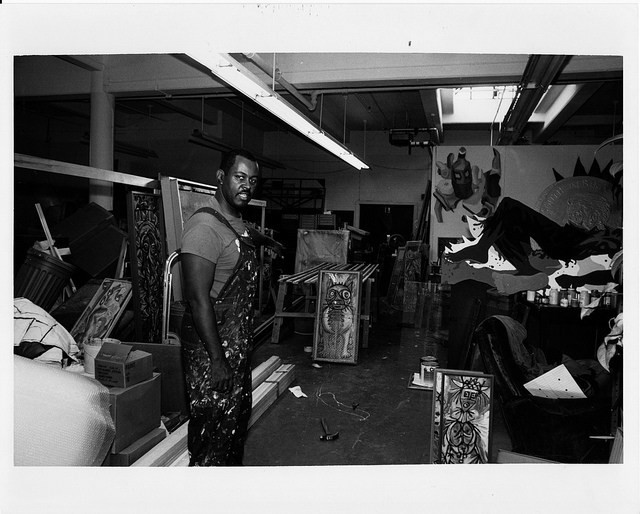

CG You were a prolific artist.

DC I was and still am.

CG What is the work since then?

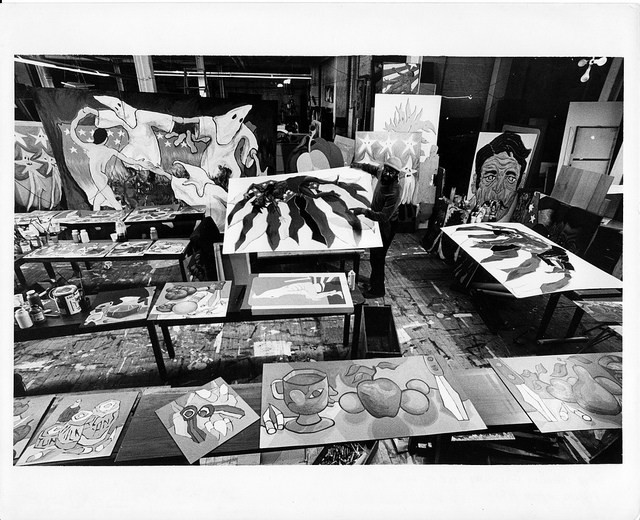

DC Still pretty much in the same vein. I have three to four hundred paintings. I have close to a thousand collages.

CG We are both 74 and have concerns about our legacy. Are you giving thought to preserving the work through your heirs?

DC My daughter is very good at archival kinds of work. She put a Facebook page together for me. She's working on becoming my agent.

CG Do you have a gallery or agent?

DC No.

CG Have you had success in selling your work?

DC Absolutely not.

CG You have an extensive exhibition history including important museum shows. In addition to the centennial show curated by Barry Gaither you were shown at the MFA by Amy Lighthill, You were included in the DeCordova survey and publication of Boston Painting.

DC The DeCordova bought one of the paintings which were in that show. The MFA had a print of mine in that recent book they did.

(Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA Publications, 256 pages, $50, January 2015. by Lowery Stokes Sims, the William and Mildred Lasdon Chief Curator o the Museum of Arts and Design and former president of the Studio Museum of Harlem, along with contributions by Dennis Carr, Janet L. Comey, Elliot Bostwick Davis, Aiden Faust, Nonie Gadsden, Edmund Barry Gaither, Karen Haas, Erica E. Hirshler, Kelly Hays L'Ecuyer, Taylor L. Poulin, and Karen Quinn.)

The print was a part of a gift to the museum from an anti war group. They never purchased any of my work.

CG How did the destruction of your studio lead to AAMARP?

DC I needed a studio space. I talked with Greg Ricks who was the dean of students. He became the dean of students. At the time he was the head of the African American Studies program.

(The John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute was formed after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.)

Northeastern had these huge factory buildings. They hadn't yet done anything with those buildings. They tore down a lot. Part of one of these buildings housed the African American Studies Department. When I talked to Greg he promised to get me some studio space in the Institute and he gave me a room. I thanked him and put all of the stuff I had managed to salvage in that room. I filled it from top to bottom. When he looked in the room things fell on him when he opened the door. I said "Well I need a little more room." He asked "How much room do you need?" I said "Well I could use the building." He looked at me like I was crazy. The building was on four levels and I was capable of filling it with all kinds of art work and stuff.

He tried to get me some space in the African American Studies Department on the fourth floor on Leon Street. They weren't able to offer me anything that was suitable for what I was doing.

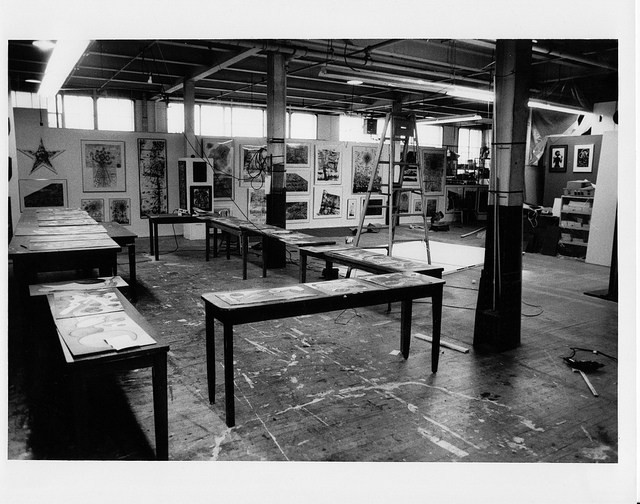

Eventually he invited me to take a look at a space on the second floor. It was about 8,000 square feet of factory space. It was for fabrics so there were old sewing machines and a bunch of other stuff. I said "Give me the key." He said "We have to clear it out first. It will take awhile before you can move in." I said "Why can't I move in now."

If you remember that space it had an elevator that opened up on my floor. So you could move stuff in and out. In the summertime I had 14 hours of daylight.

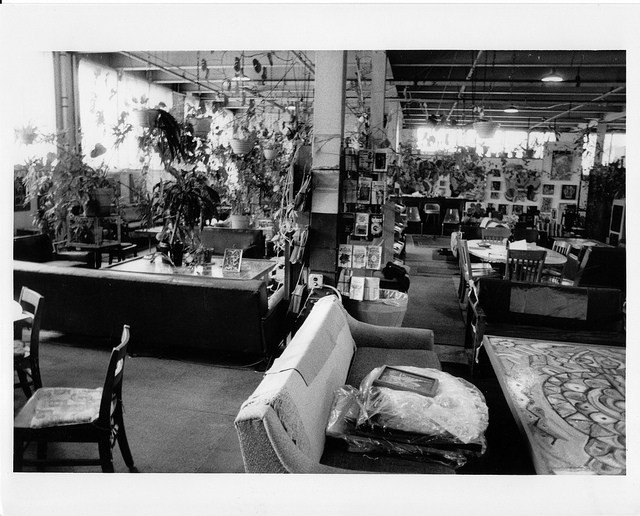

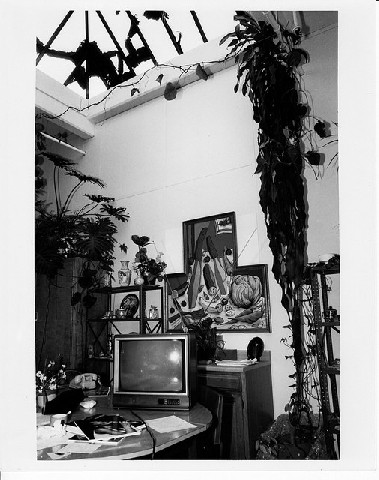

CG I remember a lot of plants. It was like a jungle.

DC Yes I did. I loved every minute of that.

CG Was it rent free?

DC Yes. I got that space in return for teaching a course in the African American Studies Department. I was available for students to come and talk about art and explore my studio. That's what led to AAMARP because it was on a floor of a building that had 32,000 square foot space. I presented a proposal for the creation of an African American artists complex that would have studio spaces and galleries as well as a community space for all kinds of events. The community space was about 4,000 square feet. It's still there but not in that building. It's at 76 Atherton Street on the Roxbury side of the old Jamaica Plain.

CG Tell me about the fellows.

DC I started off with 13 or 14 fellows. Ellen Banks.

CG I knew her well and have one of her paintings. It was in exchange for a catalogue essay.

DC Me of course. Milton Derr.

CG Sure. I reviewed one of his Northeastern exhibitions.

(There was a gallery in the library which was later discontinued. That's where we moved the "Kind of Blue" exhibition from Provincetown working with Professor Myra Cantor. I also wrote a catalogue essay for one of her exhibitions of portraits.)

DC Tyrone Geter. Reggie Jackson, Arnold Hurley, Jim Reed, Rudy Robinson, Barbara Ward, and Teresa Young. These artists were actually in residence. Calvin Burnett and John Wilson were associate artists who had their own space. They were connected and exhibited with us whenever we had shows.

At AAMARP we had shows of everybody's work. In the years that I was there as director we did over a hundred exhibitions. There was a whole series we did on Irish art. We did a show based on Irish cartoons in the 19th century around the issue of the Irish and black discrimination. I can't remember the name of the show but it's part of all that. There was somebody Nash who was a cartoonist in those days.

CG Nast. He did the cartoons about Tammany Hall.

(Thomas Nast, September 27, 1840 – December 7, 1902, was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon". He was the scourge of Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine.)

DC That's the show we had with all of his cartoons.

CG That's what I was asking you before. Your relationship with the art of social protest. What for example was your relationship with Arnold Trachtman?

(Trachtman, a graduate of Mass Art, has been a leading protest painter in Boston. When a show of his Vietnam paintings was shut down at Harvard, working with ICA director Drew Hyde, we moved the show to the ICA building in Brighton. Like Dana and myself he showed at the Community Church Art Center in Copley Square which was devoted to activism in the arts. Arnold now shows with Galatea Gallery in Boston's South End.)

DC Arnold was one of my favorite people.

CG Ok. Now we're getting somewhere.

DC In my opinion he was (is) one of the great social protest painters. What's happened to him.

CG He's now on in years (older than Dana and myself). Mark Favermann has reviewed his recent shows for Berkshire Fine Arts. I have worked with Arnold over the years as has Pat Hills (now retired from the art history department of Boston University).

Moving on what can you tell me about the recent donation of African American art to the MFA from the Axelrod collection?

(Sixty-seven works by African American artists have recently been acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), from collector John Axelrod, an MFA Honorary Overseer and long-time supporter of the Museum. The purchase has enhanced the MFA’s American holdings, transforming it into one of the leading repositories for paintings and sculpture by African American artists. The Museum’s collection will now include works by almost every major African American artist working during the past century and a half. Seven of the works are now displayed in the Art of the Americas Wing, in time for its one-year anniversary this month. MFA press release 2011)

DC Except for the book ("Common Wealth") I don't know it very well. If I comment on the collection it would be about the art itself. He has a lot of very good pieces. A lot of early pieces from a lot of artists. Most of it is lesser work. I did not see anything that I would consider to be masterpieces.

CG Have you seen the work installed in the MFA?

DC No. I haven't lived in Boston since 2004. I live in Gallup, New Mexico.

CG How did that happen?

DC African American male issues have been ongoing. It sounds like a preamble but it really does relate to what I'm going to say. When I moved here my son was a teenager. He was 16 and the year prior to that he was being courted, sort of, by the Crips and the Bloods.

The courtship went like this. You'll join one or the other of us or we'll kill you. My son was and is, if pushed to it, an extremely good street fighter. If you're 250 pounds and think you're going to kick his ass because he's a little skinny guy, you're in trouble. He's that good.

He would go to Forest Hills and they would meet him with somebody who would challenge him to a fight. He was fighting every day and would come home with a bloody nose, scratches on his face. The other guy? Oh well. He was very good at knocking people out. He told me "If I stay here by the time I'm 16 I'll either be dead or in jail."

Since my life experience included that when I was a teenager I knew exactly what he was talking about. So I said here's what we'll do. I'll retire. I was 63 at the time. We'll move wherever you want. So pick a place. He picked New Mexico because he met a Navajo and he was very heavily into his Native American heritage. We are African Native Americans. From several different families of Natives. We are Oglala Lakota. Part of the Sioux family. It was in the Dakotas.

My branch of the family was chased out of America into Canada and ended up in Nova Scotia. That's where my grandmother was born in the 1880s. The Lakota fought the army for many years. When the army got to be more than they could handle the army chased them into Canada and they made their way all over Canada. A number of Lakota people ended up in Nova Scotia.

CG Where does your African heritage come from?

DC My father's side is native and my mother's side is African. From Barbados.

CG Where did your parents connect?

DC A little town called Lynn, Massachusetts.

CG Are you going to write your memoirs?

DC I've written some of it. That will take some time because right now I am trying to get my work together because I want to do a retrospective at some point. The challenge is what everyone has. How to do the retrospective that I have in mind. With no money. Like a lot of African Americans I forgot to take care of the money aspect of things.

CG That's true for most artists. Having pursued a career of supporting contemporary art in Boston very little of the work and careers of artists I have written about has made it into the mainstream. Most of the work I have been involved with is slipping off the radar. Which is why this oral history project is important. It is an attempt to preserve aspects of our legacy. When we're gone an important period of our culture goes with us.

DC I would agree.

CG Even though we enjoy a love/ hate relationship there is a nostalgia for it. This has been an important aspect of my life.

DC I enjoy it immensely. You were one of the critics who taught me not to worry about what critics have to say.

CG Thanks so much for ignoring me.

DC Pretty much. You would write your things and I would go, Ok. That's Charlie and I moved on.

CG I was responding to you in two ways. On the one hand Dana Chandler the activist and on the other Dana Chandler the artist. Is it possible to separate them in terms of writing criticism? How to treat an individual who has a prominent profile as an activist and also wants to be evaluated in a formalist sense as an artist. It's hard to unravel and separate out those threads. It becomes a Gordian Knot.

Wearing different hats and taking on multiple roles as critic/ artist/ curator has been problematic for me as well. Because of my profile as a critic there has been prejudice against accepting my efforts as an artist. I was in a group show at the Boston Center for the arts. The critic for the Phoenix wrote about every artist but me. I asked him about it and he said "You can be either a critic or an artist but not both." So this is an issue for a lot of us with multiple roles in the arts.

DC Whatever my legacy is I won't be here to appreciate it. My children will be here to appreciate it. For me it's hard to get excited about legacies that I won't see.

CG That may be but I feel you have a responsibility to put things in order for your heirs. It's a common issue that I deal with. I get a lot of calls from heirs of estates. And I am reminded that I have to put my own life in order. That's a part of the motive in wanting to talk with you and others who have been key players in a rich but ephemeral cultural history. We are preserving essential information for future generations.