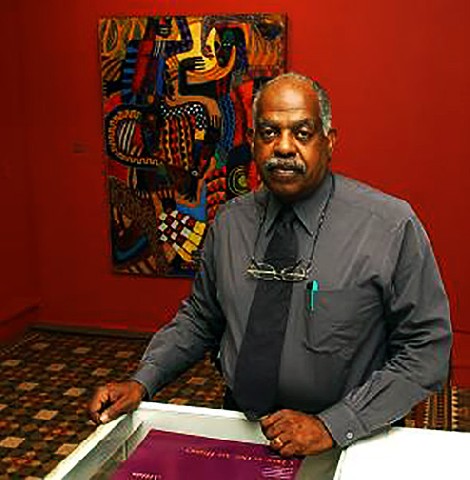

Barry Gaither Part Two

Building National Center for African American Artists

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 28, 2015

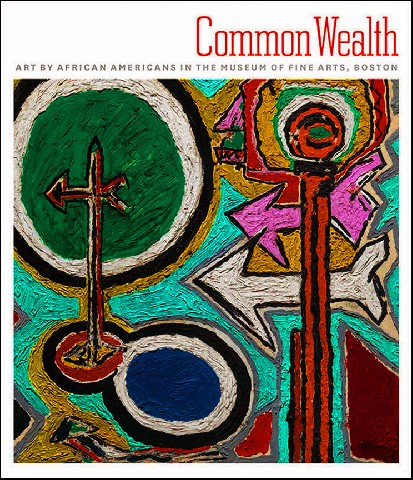

Charles Giuliano There is a media perception that the MFA programmed African American art primarily as a response to social and political pressures that were prominent in the late 1960s and 1970s. As the paradigm shifted has there been a backing off in the level of programming and support? What is the status today and how has that shifted with the acquisition of a major body of work from the collector John Axelrod?

Barry Gaither I see the period from 1969 through the end of the 1990s as a time when I did a lot of work there. It included exhibitions but also a lot of performance events which were related to exhibitions. It brought to the MFA a lot of audience, particularly a black audience, which otherwise would not have been so involved.

Through that period the kind of changes that my work represented were not really institutionalized. Other than my putting forward suggestions on a fairly regular basis which got acted on they didn't tend to come from elsewhere.

I think the changes that came about have three conditions which made them possible. One condition is that large museums respond powerfully to donors who are holding what are perceived as important collections. So to some degree the emphasis I was trying to push was never going to get traction until a collector came forward to anchor it. That's what Axelrod did.

The second thing that has to happen is there has to be a greater amount of ownership of the topic. When I did the John Wilson/ Joseph Norman exhibition at the MFA in the early 1990s I did that with one of the young curators from Cliff Ackley's department (Prints, Drawings and Photography). It was a show fundamentally about prints and drawings. That was all very good. That was the closest things came to having another department at the MFA embrace this topic. Before we get to the changes that came with Malcolm (Rogers whose mantra was One Museum).

The curatorial emphasis beyond the one I was making took a long time to get any traction.

The third condition is that there has to be some commitment of money to actually sustain the change. In this case the money was closely tied to the coming of the Axelrod collection. Here is the frame you have to put this in Charles.

In 1970 when we were pressing, by we I mean the African American community with its various pieces, the audience, we at the Center, that was very much a hot discussion. They were being asked to do two things. To make African American art and artists an essential part of what they put forward in an encyclopedic museum. They were also being asked to do the same thing with African subject matter. Neither of those had curatorial favor at that point in time.

In 1973 I think it was I brought "African Art of the Dogon" to the Museum of Fine Arts. That work is now largely in the Metropolitan Museum that they received from Lester Wunderman. In 1980, I brought "Contemporary Art of Senegal." Those exhibitions expressed our point of view that we wanted to get a recognition in the MFA at a curatorial level of the visual arts heritage of the global black world. African American was important in that but it was never separate from this larger view.

When Merrill Rueppel was director there were some steps toward the African piece of this. That didn't fall in place until the Teel Collection.

(The African art galleries at the Museum of Fine Arts opened in 2004. The collection consists mainly of artworks collected by Bertha and William Teel, who donated part of their large African and Oceanic art collections to the MFA. The Teels sponsored the installation of the galleries and endowed the MFA's first position of Curator for African and Oceanic art. The museum's catalog presents one hundred and five works as masterpieces. Although the Teels started their collection of African Art in the 1950s with two Dan masks collected originally by Harley, the earliest collection dates for pieces represented in the catalogue are 1968 and 1969. To a large extent, the collection seems to have been brought together in the 1980s and 90s. This opens up an array of questions regarding authenticity, age, and provenance for the artworks.)

These core changes in the collection have only been able to be consolidated when there has been a major collector whose gifts have provided an anchor. Around which that change could happen. My work provided a lot of preparation for that. None of that could get harnessed until those collections came forward to become part of the content of the MFA.

CG What role did threats play in these changes? Dana (C. Chandler, Jr,) takes credit for initiating the exhibition "African American Artists from New York and Boston." To what extent was activism a catalyst? Around that time a work by John Singer Sargent was vandalized. I'm sure that disturbed the trustees. On the one hand in Dana's version there is activism and then talking with you there is a measured, rational, methodical blue print for moving forward. The issues are complex and I am trying to sort out and understand the components.

BG I'll give you a little model to think about it. You could think of this as Dana shaking the tree and we were harvesting the apples.

CG Talking with him today his position is largely unchanged. He feels that nothing has really changed or been accomplished.

BG You have to look at the balance between what has been accomplished and what is accomplishable. The MFA when all is said and done is a great encyclopedic museum. Nobody is creating those anymore. Those are animals that are out there and are not really challengeable in terms of something new. What we call upon them to do is to be true to that notion of encyclopedic. Because the encyclopedic approach represents the sum of the visual arts traditions of the human condition.

The old model was a very narrow one which simply denied that huge portions of human kind had contributed anything. It essentialized even then a fairly narrow reading of the West as the standard and the measure.

What we started trying to change was the assault in the 1960s on these great encyclopedic museums. We wanted to force them to give critical recognition to this larger, truer picture of visual arts production. I think it is very difficult to say that indicator hasn't moved hugely. Parallel to that the other thing that has to be said is that the visual arts life of a great American city cannot be summarized in one museum. It cannot be because there are too many contributors from too many perspectives that are valid.

In order to have the quality of dialogue, exchange of friction, to have challenge and resolution that makes for healthy growth intellectually, spiritually and imagination, you have to have multiple entities at play. I never expected that the Museum of Fine Arts can be everything the black artists need. The reason we exist (National Center for African American Artists) is because we embody a different perspective.

If our whole purpose was to represent what the great museums a generation ago didn't do then when they finally got around to doing some of it then we would have no purpose. Just because the Frick doesn't close down because there are other collections. Just as the Fogg doesn't close because there are other places to see medieval art. Put this in perspective from a point of view and history and the aggregate of them may provide the totality of the scene. We represent a very particular point of view on where black creative life really ought to be. Our big problem is that we have not been able to build structure strong enough to actually bring that critical voice forward.

I don't expect the MFA to shut down all of the other departments in order to raise the discussion of the black visual arts globally. I expect them to give it a fair share in the mix of things.

CG What is the status of your museum at this time?

BG In the late 1980s we looked at ourselves and said we will never be who we want to be unless we find an economic model that gives us some viability and growth. So this was a decision taken by the National Center at large and the museum included. We sold off the properties that we owned on Elm Hill Avenue (Roxbury).

We decided to invest in a really huge gamble. When we looked around, and I played a leading role in this, we needed to find a model which would rest more heavily on unrelated earned income.

In the United States museums exist only on three models. They exist as owned by other institutions like universities. Harvard owns more than a dozen museums. They're somehow tied to government and city, county, state or whatever. Or they have endowments.

Our opportunity to quickly build an endowment of the size to support being competitive and operating in this environment wasn't great. I looked at places like the Museum of Modern Art and saw they were trying to figure out ways to monetize assets that previously hadn't been given a lot of thought. This came to me when I paid attention to how they sold their air rights. They converted empty space that happened to be above them into money. We looked around at what might allow us an opportunity to develop a significant model based on unrelated earned income.

There was a huge parcel of land that had been denuded in the urban renewal effort in the very end of the 1960s. This is the strip of narrow land along Tremont Street. It's where presently Roxbury Community College is as well as the Reggie Lewis Running Center. There are some eight acres left which we have decided to develop.

Another thing was going on at the time. A close supporter of ours, a black developer, an associate had gotten the property where the Cross Town Center is now. It's where the Hampton Inn is. They had gotten that piece of land through direct designation and developed it. We thought we can do that model so we hired the developer who did that model. We sold off the property on Elm Hill Avenue and reinvested a significant amount of the money in trying to become developers of Parcel 3P in Roxbury. In order to do this we retained Graham Gund's architectural firm because we had a relationship with him through the MFA. We entered that fray.

At the beginning of 2007 when development in Roxbury came back on the city's agenda it immediately ran into the bitterness of land takings when Route 95 was going to come across Roxbury. They wanted to shield themselves from that. So the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) decided that the way to do that was to commission a new master plan for Roxbury that would then create a means for the distribution of public land in Roxbury. Such a thing was put together around 2000. The BRA was supposed to have 18 months to develop a plan. It took two and a half years but delivered a plan which then made it impossible to get a direct designation.

Not to get a designation you have to go through a more complicated process with the BRA. So we entered this more complicated process. We won against two commercial developers a tentative designation for this parcel in 2007. We were planning a mixed use development with 250 units of housing, a major presence for health care, office tenants, smaller retail. The model was designed such that we would get three things. We needed a new facility, built, outfitted and delivered to us without debt. We needed a sufficient interest in the overall project so that we would have an annual income tantamount to endowment, and we needed enough success to leverage the renovation of the 19th century building that we were presently occupying. It was the only property we kept from the property which we had previously owned.

As soon as we had the tentative designation the markets collapsed. Our financial partner, who was a New York based investor, lost his shirt in the housing collapse on Long Island. We spent the next period of time fighting with the BRA to keep our designation and we succeeded.

So we get to 2010 finding a new financial partner who we are still with. It took us a year to work out an agreement between ourselves and our financial partner to guarantee that we got the things which I just itemized.

In 2013 we thought we were headed for the home stretch. When the new financial partner came on we had to respond to changes in the economic environment than were a consequence of the market collapse in 2008-2009. That was compensated for by re-balancing our plan that we now had large retail as well as small retail as economic engines in the mix.

A year and a half ago as we thought we were headed toward being done with this. Mayor Menino called us and said he wanted to keep Partners Healthcare in Boston. They represented 5,600 jobs. Could we find a way to accommodate them in our plan? We felt we had no choice but to try to do that. We spent three quarters of a year trying to accommodate what they needed. We did in fact accommodate it but in the end the entire thing had been a ruse. They had intended to go to Somerville all the time. They intended that they would ask us for so much that it would be impossible to deliver and they would then have a clean reason to leave. It didn't work out that way. Nevertheless they left. In December, 2013 it went out the window.

The mayor is changing and we come into 2014 trying to get back into our stride. It takes the first three months of 2014 to figure out what's going on at the BRA. Who's in charge? Who's doing what? Then we get a new mega-tenant who wants to be in play. This time it's the department of transportation. The city wants us to accommodate them so we spend most of 2014 trying to figure that out. We were supposed to get to irrevocability with the department of transportation before the governor left. The governor (Deval Patrick) had been very interested in seeing all this to happen. But it didn't get to that level of the negotiation. Now we are waiting to see if the Department of Transportation is going to stay in this deal or not. And what impact that's going to have on us. Which could be good or bad.

The bottom line is that we still have immediately before us what we hope will be the development opportunity to create a mixed used development on that site which will be known as Tremont Crossing. Where culture and commerce connect. It will give us a new museum of 31,000 square feet, built, outfitted and paid for and delivered free of debt. We would retain almost 40% ownership of the total project. It now includes 200 units of housing, 400,000 square feet of large retail anchored by BJ's, another 60,000 for smaller retail, another 160,00 of middle retail, a flag hotel of 170 rooms. That would give us in earnings close to $2 million a year and a new facility. Those would leverage where we are.

I stopped doing the level of work I had been doing at the MFA. I also reduced the level of work I had been doing at the National Center. Because, frankly, I spent most of the last decade trying to get this development to happen. Because it would be the literal guarantee of our future and consolidation of the work that we've done. So that's what's been happening.

I was presented with the decision of whether we should suspend and work our way through all of this. I thought that was a bad idea. I thought it was better to go to skeletal and get through all of this. Then reemerge out of it.

Over the course of the next six months if we can get to real clarity and get a guarantee that we are going to be able to come out of this project we will then enter basically a two year planning process that will revisualize what the museum should be for the millenium that we're in. I would be looking at that emerging as operational in perhaps 2017 or 2018.

I am looking forward to handing it over to lots of young people who want to do it. But I do want to have a lot to say about the vision of it.

CG So what else is new? (both laughing)

BG This has become my life's work. Nothing would make me happier than to see that consolidation happen.

A deep motivator in all this Charles, beyond the obvious, is honoring the legacy of all of those of us who worked so hard with Miss Lewis. When I came into the museum field I didn't think in terms of creating a white museum with black subject matter. I had the idea that we could evolve something really new and different that was responsive in a way it hadn't been before. Very early on it became clear to me that the terms of survival were very conservative terms. We've lived as much and as best we could in that framework.

If we had our own money then I would really like to be able to exercise a genuinely critical voice. Which we are at pains to do in the present environment. I would make a quite different picture of what contemporary black art is than the half dozen people who are the measure of it right at this moment. Not that I don't think those are good people. But they are hardly the sum of what it should be. I think you don't get a lot of new candidates thrown into the mix unless you have institutional structures that can hone them. And can sponsor discussion and writing about them that can put them into the mix.

In the absence of that you have a limited number of curators who basically recycle the same people. That's not where we ought to be.

CG From the outside looking at African American art today most people in the art world would say what's the problem? There's a highly visible A list of successful and renowned artists. That creates the perception of a level playing field.

BG When you don't have the investment to see something as a tradition then you can settle for that. But when you see something as a living tradition that has in the back of it hundreds of years of development and in front of it infinite possibilities then you say that a tradition can't be half a dozen people. A tradition is like an enterprise. It's a very large number of people. There's a visceral quality to all of this that I don't want to be lost.

CG Going back to 1970 when you organized that first show for the MFA those 70 or so artists were largely unknown. One might argue that those artists continue to be unknown to the mainstream. There wouldn't be an incentive to put on such a broad survey today. There isn't the need to prove to the world today that there is a critical mass of accomplished African American artists. There are now enough of those artists who are visible in the global mainstream. They're out there. In Great Britain there's Chris Ofili and Yinka Shonibare. From Africa El Anatsui as well as the A list of African American artists. There has been a paradigm shift. We are talking from an era with an African American President, Attorney General, Supreme Court Justice, governors, mayors, members of congress, business CEO's. That wasn't true in 1970.

BG You have Ferguson.

CG That's Dana's point. Plus ce change plus c'est la meme chose.

BG It think it confirms the complexity of human environments. If we had an estimate of human kind then we would like to think that a net gain corrects the problems. But if we accept that human movement forward is eternally contradictory, nuanced, unsteady, not strictly linear, then we see that on some counts we make large gains and in other places lag. We have to affirm the value of having agency for yourself and the things that you believe in. Because ultimately the existential proposition is that we make the world by our actions. It's our agency that we must have. Whether we win or loose matters less than that we acted.

CG I have a friend with whom I am in a constant dialogue about these issues. It has been a broad ranging discussion of research and writing about jazz, theatre and the arts particularly when there is an aspect of race. He is an important mentor in keeping focus when the thinking and writing gets off course or encounters obstacles. Today we were talking and he reminded me that there is a hard core of at least 20 to 25 % of our nation which is deeply racist and resistant to change. Set against that is a projection that there is a time approaching when white America will dip below 50% of the population. One notion is that what we are seeing is a violent reaction to that process of inevitable change.

BG All of that is true. There is a fear of change precisely because there is some degree of change. If you just look at Ferguson. That's an easy one because it's so much talked about. The protest that grew up around that grew up around an issue that's totally not new. Nobody growing up in black America over the course of the 20th century was unfamiliar with the kind of discrimination and the killing of young blacks that happened. That wasn't news. It got made news because a newer group of young people through social media were able to raise it and they were supported by a surprising number of non blacks. Who joined in for the first time. Those people joining in for the first time represented change.

In all the history when these things happened as straight ahead lynchings with the kinds of scenes which Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit" conjured there was no large body of white people chiming in anywhere to say 'how dreadful.' There was silence for the most part. That there wasn't silence this time is progress. The people who were upset about it were so because there was change. If there hadn't been other people joining in to raise this issue then there would have been less dialogue about it.

CG Reading the history of the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts and the later buildings she took over on Elm Hill Avenue it seems that there were a series of fires and then an ultimate act of arson that destroyed the property. Since she was primarily focused on arts and education can you discuss these actions targeting her efforts?

BG I can share well grounded opinions. They were not fully adjudicated but from what we could see on the inside what seemed to be the case.

The two fires that happened at Elm Hill Avenue were arson. Of that we're sure. Who the agents were is a little less clear. There are two suspects let's say.

We were in the way of the takeover of that whole area by the drug traffickers. Crack had made a dramatic entrance into Roxbury. The epicenter of the crack epidemic was Cheney Street. It was directly behind out properties. We suspect there might have been an effort to get us out of there. As a force in a different direction.

There's another possibility either directly or indirectly that the fires were caused by Rabbi Meier Kahane the director of the Jewish Defense League.

(Rabbi Kahane, August 1, 1932 – November 5, 1990, was an American-Israeli rabbi, ultranationalist writer, and political figure, whose work became either the direct or indirect foundation of most modern Jewish militant and extreme right-wing political groups. He was an ordained Orthodox rabbi and later served as a member of the Israeli Knesset. Kahane gained recognition as an activist for Jewish causes, such as organizing Jewish self-defense groups in deteriorating neighborhoods and the struggle for the right of Soviet Jews to immigrate. He later became known in the United States and Israel for violent terrorist attacks as well as political and religious views. He was killed in a Manhattan hotel by an Arab gunman in November 1990 after concluding a speech warning American Jews to emigrate to Israel before it was "too late.")

He was an enemy of Elma Lewis. He had been an enemy since the acquisition of the properties in the late 1960s. He was an enemy to the degree that he had read into the Congressional Record in the early 1970s that we had been responsible for acid being thrown in the face of the head of Stanislawsky's Mortuary on Blue Hill Avenue. He had read into the Congressional Record that we were teaching hate. When Miss Lewis won the MacArthur Award he tried to intercept the prize.

So there was a bitter history with that fringe within the Jewish community that went back to the deal around the properties. Because it had been so consistent we could not rule out that he didn't have a hand in it in one way or the other.

CG How old are you?

BG 70.

CG I'm your senior. Talking with you and Dana about those events in the 1960s and 1970s brings back memories of the roles we have played in Boston's cultural history. Hearing your narrative of the struggle to create a museum and solidify a legacy evokes mixed responses. On the one hand it conveys great accomplishments and a life well spent and on the other a sense of constant and daunting resistance and frustration.

BG Looking at this sometimes I feel that my life has alternated between being a bride and an albatross. Some days I look at this work and say that it's miraculous that we're still here considering the odds that we have wrestled against for all of this time. This is not much to show for a life. Other days I look at it and say every great tree including the redwoods in California were one day seedlings. They were seedlings for a long time before they were great trees.

Gaither interview Part One.