Drew Hyde Was Seminal ICA Director

Led Institute Back from the Brink

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 29, 2020

If the counterculture started during 1967’s Summer of Love in San Francisco, there were aftershocks on Boston Common. With a more political spin of social and political zeitgeist flower power morphed to Boston in 1968.

There was a heady mix of youth and creativity that pervaded from Boston Common to Harvard Square. There was something in the air.

The Buffalo Sringfield song “For What It’s worth” captured the mood of its generation. “There's something happening here What it is ain't exactly clear There's a man with a gun over there Telling me I got to beware I think it's time we stop, children, what's that sound Everybody look around.”

That message was heard on WBCN-FM, The Rock of Boston, through Avatar, and the emerging underground press. British Invasion and emerging American bands performed at the Boston Tea Party in the South End. Joints were shared on Cambridge Common during free Sunday concerts. Van Morrison, then living on that side of the Charles River, composed “Astral Weeks” in 1968. Between Tea Party gigs the Allman Brothers crashed in Cambridge.

Through all aspects of its social and political order, staid, Brahmin, conservative, racist Boston was getting an extreme makeover.

For the right time and place there was new leadership with a 38-year-old Mayor, Kevin White (1929-2012) who held office from 1968 to 1984. There was a symbolic move into the New City Hall in 1968, designed with brutalist style, poured concrete by Kallman, McKinnel and Knowles.

As a signifier of change its inverted ziggurat design was erected on the site of the razed Scollay Square. That had been the epicenter of the red-light Combat Zone that then shifted and eventually petered away on lower Washington Street.

That transformation ripped the heart and funky soul out of the old Boston, with its mix of bars, burlesque, and used book stores. Massive demolition created a vast plaza. There were analogies to those in Italy where citizenry gathered and debated. Indeed, City Hall Plaza has been used for rallies and parades including sports celebrations.

The gutting of Scollay Square almost extended to adjacent Quincy Market the city’s colorful meat, produce and flower market. It was the tail end of the disaster of the era of Urban Renewal in which Boston lost its flavorful, multi-ethnic West End. It had conflated with the more downscale back side of socially prominent Beacon Hill.

By the early 1970s the meat, produce and flower markets relocated to more adequate facilities. That begged the options of razing or renovating.

In 1969 there was a grant to repair structures of the Alexander Parris designed, neo classical buildings. By 1976, designed by Benjamin Thompson and Associates, with Rouse Company as developer, it reopened as the New Quincy Market. It soon became a magnet for shops, restaurants and a destination for tourism. Per square foot it has the highest retail cost and visitation of any tourism destination in America.

It barely escaped becoming yet another inner city parking lot.

This serendipitous extreme makeover became a paradigm for reuse architecture. The firm of BT&A went on to find similar success renovating the waterfront of Baltimore.

The young mayor White had challenges with an inflamed city during court ordered school bussing 1974-1988. Primarily Irish American South Boston exploded. There was unrest in African American Roxbury and Dorchester. The city is notable for its ethnic neighborhoods.

There is the memorable Oscar Handlin study “Boston’s Immigrants: 1790 to 1980: A Study in Acculturation.” It tracks how waves of immigration transformed neighborhoods and created ethnic clusters. That disparity was a challenge to White and his administration as unifiers and peace makers.

Surrounded by talented and energetic staff including Barney Frank, deputy mayor Kathy Kane, and emerging leaders Ted Landsmark and others the White administration sought to activate and politicize the arts as a force for social justice..

On the cusp of White’s administration was the Summerthing program in 1967. Promoters John and Leah Sdoucos were hired to book concerts in neighborhoods. By 1968 they organized Concerts on the Common which developed into the Sunset Series below the State House flanking Boylston Street. When the nation saw urban riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King the Mayor had a hand in keeping the lid on. A James Brown concert at Boston Garden went on as scheduled and was broadcasted live by WGBH and looped all that weekend. Boston stayed cool.

Through Summething a young architect Edwin Childs renovated abandoned lots into mini parks. There were volunteers including Adele Seronde. Public art was commissioned to bring emblematic pride to communities. African American artists Roy Cato, Jr., Dana C. Chandler, Jr. and Gary Rickson painted murals. Emerging artists Michael Phillips, Curtis Crystal, Bill Jacobson and David Kibbey among others painted murals and created sculptures along the Charles River.

A college dropout (Washington and Lee), Andrew C. Hyde, from a socially prominent family relocated to Boston and went to work for Summerthing.

Working closely with White and Kane there was an opportunity to expand his role.

During the summer of 1968 I wrote an article for the Avatar “ICA on the Move.” For a variety of reasons the administration of Sue Thurman (1927-2012) director 1963-1968 ended. The Institute was evicted from New England Life Hall at 100 Newbury Street and put in storage at its former inadequate, abandoned facility of Soldier’s Field Road. It was a loft like structure constructed with industrial materials. The home for the ICA in an inaccesble location was designed by ICA founder Nathaniel Saltonstall.

The ICA had gone belly up and indeed after years of up and down, mostly down since 1939, it was at a dead end.

Arguably, that demise was justified. But a new sensibility and political muscle was pulsing through dusty old Boston. Then unemployed and living by his wits, with a little help from some friends, Hyde was looking for a gig.

Kathy and her husband Louis Kane had long been supporters of the ICA. They had every reason to resurrect the ICA particularly with help from White’s clout. Louis bought the An Bon Pain franchise in 1978. They were wealthy, progressive, and well connected with other potential ICA supporters.

The bona fides of Hyde in education and the arts were questionable. Shortcomings were more than compensated by charisma, charm, energy and roll-up-your sleeves ambition. Drew grasped the brass ring and ran with it with a tether to City Hall through the Kanes.

With no money for staff, administration and programming he prudently connected to the energy of an emerging generation of artists. It proved to be an effective alliance. As the ICA gained momentum funding and support from City Hall increased.

By the fall of 1968 Avatar which Dave Wilson, Sandi Mandeville and I published ceased operation. They went back to Broadside, a music publication, and I signed on as design director of Boston After Dark (under Stephen Mindich later The Boston Phoenix). My incompetence for the position was soon apparent but I stayed on as art critic with a weekly column Art Bag. With which I put out a call for artists.

There was a dinner party in the South End apartment of the artist Andrew Tavarelli and his then poet wife now the artist/ musician Jane Hudson. After dinner they invited some of their artist friends. What came out of that was a seed that spread.

In 1969 a group of artists formed the Studio Coalition. It proved to be the nation’s first open studios event and earned a cover story in Boston’s Gallery Guide. I covered it for BAD and the story spread to national arts media.

Curator John Chandler (later with Hyde’s ICA) and I convinced Newbury Street gallerist Phyllis Rosen (Obelisk Gallery) to have a show of the new Boston artists. Chandler organized “Three If By Air” with Tavarelli, Tony Thompson and Kathy Porter.

By 1970, with the ambition to take on larger work and more ambitious programming Rosen and her partner Joan (Stoneman) Sonnabend, joined forces with gallerists Portia Harcus and Barbara Krakow. Across the tracks from the Museum of Fine Arts, on the edge of Roxbury was Parker 470. One of the first shows, The Boston Band, featured emerging artists.

Again we approached Rosen to use the space for meetings with artists. One of those meetings entailed an evening with MFA director Perry T. Rathbone moderated by Thompson. The large space was packed. Rathbone was feeling the heat from an attentive but polite audience. That changed when Joan Trachtman bluntly asked him when the MFA would appoint a curator for contemporary art. There was a humorous event Flush with the Walls that was a sneak attack on the MFA. Artists organized an exhibition and vernissage in the museum's men's room.

Not long after that Rathbone called me at the Herald Traveler to announce that he had appointed Kenworth Moffett as the first curator of contemporary art. Intially, then a professor at Wellsley College, Moffett worked part time at the museum.

There was the sense that changes were happening at warp speed. The artists, in 1970, organized the Boston Visual Artists Union (BVAU) directed by Mark Favermann. It had several physical manifestations including a gallery in the Crescent opposite City Hall.

With programming springing off the energy of emerging artists Hyde’s ICA was once again viable. Given its inaccessible Charles River location there were large openings but not much foot traffic. I convinced Hyde to let me curate a show of protest paintings by Arnold Trachtman. Because of its antiwar content the exhibition had been shut down from one of the Harvard houses.

Playing a political trump card Hyde programmed the City Hall Gallery as an ICA space. There were memorable exhibitions including Boston Now. That later became an annual ICA feature during the administration of David Ross. I co-curated with Hyde a show Images that featured the new realism. The city later took over the space for city councilor offices.

Education was a large aspect of Hyde’s mandate. When we were installing at City Hall with an impish expression, he opened a closet. It was stacked with cameras for kids donated by Polaroid.

Drew had the touch for acquisitions including city owned properties. The ICA yet again abandoned Soldier’s Field Road and moved into the Parkman House on Beacon Hill a short distance from the State House. Viewed as temporary quarters the mansion had less than adequate space for ambitious exhibitions curated by Hyde and Chandler. There were public art projects including "Monumental Sculpture for Public Spaces." Works by major artists were displayed including a 12' "Love" by Robert Indiana on City Hall's plaza.

There was relatively brief occupation of a South End warehouse dubbed Act (Artistic, Craft, Technology) Now. That’s where Hyde launched ambitious programing with artists as mentors to inner city youth. I covered a major exhibition there Collaborations featuring emerging Boston artists. Hyde was such a notorious pack rat it was rumored he had a surplus rocket stashed there.

It took a lot of physical and psychic energy to keep up with the rolling thunder circus of the era. There was a promotion for the French aperitif Pernod. The pr people were generous in providing product for ICA and arts events. Some proved to be outrageous occasions. Drew was known for dramatic pratfalls which appeared to parallel his personal life.

There was a hiatus from 1972-1973 when Christopher Cook served for a year as a conceptual art piece. Memory of his administration, which was given a Globe Magazine feature, is ephemeral. He then returned to Andover Academy’s renowned Addison Gallery of American Art.

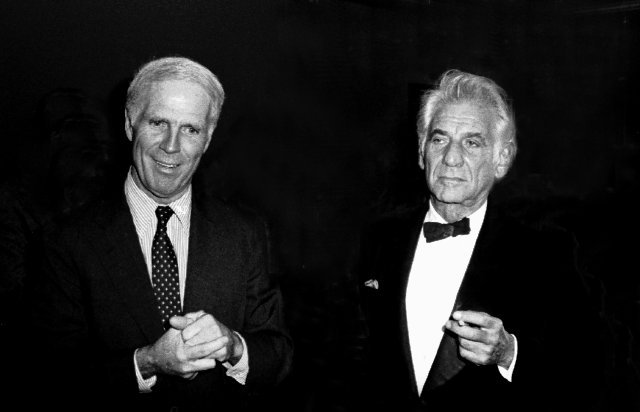

The interview that follows was recorded when Hyde returned briefly to the ICA. Playing an ace with White and Kane he negotiated finally securing a permanent home for the ICA at 955 Boylston Street.

After the ICA Hyde had a diverse career with executive positions at four of the largest mass transit systems in the country as well as London’s. He was Assistant Director of Aviation Operations at the Massachusetts Port Authority and director of Operations at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Hyde was Assistant Director and Acting Director of the Authority's Construction Department. He was Associate Publisher of a short lived vanity project, Boston Review of the Arts, and Director of Boston Children's Museum. He served as chairman, director, member or trustee of many boards and committees including the Massachusetts Governor's Task Force on Arts in Education, Adjunct Associate Professor of Fine Arts at Boston University, The U.S. Department of The U.S. Department of Labor's Construction Committee, the Corporate Design Foundation, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, and the Alaska Fund of the Future for which he served as Chairman of the Board from April 1995-May 1997. In 1986, Hyde relocated to New York City where he held the positions of Director of Public Affairs and Vice President of Development for the New York City Transit Authority. These are some of his many professional credits. After a long illness he passed away, January, 2008, in Hilton Head, South Carolina.

Simply put had it not been for the genius of Hyde’s vision and timely intervention there may well have been no ICA today.

Decades ago, I donated several tapes, including what follows, to the Archives of American Art. At the time there was a branch office on Beacon Hill run by Bob Brown. He was gathering information and conducting interviews. That satellite was terminated when the budget of AAA was drastically cut back.

It took time and effort to recover that material. What I managed to retrieve was in poor condition. Much of the Hyde tape was inaudible. What follows is what I could salvage from a 1973 conversation with Hyde.

Drew Hyde Our research revealed that there was very little being done in the arts with public high school students in the City of Boston. There was little being done for that age group. There was no Children’s Museum.

Charles Giuliano There is a Children’s Museum.

DH I know but that’s not for high school students. There are a lot of resources for elementary students but nothing for high school students. They were written off. They’re lost, we can’t deal with them. From Washington there were no special funds. There were no special funds anywhere.

CG What date are we talking about?

DH September, 1973 when I came back to the ICA. Some trustees approached me and wanted to know if I was interested in coming back. I said that I was interested if I could put together a project which I am really interested in. It entails our past three to five years in the visual arts, strong concerns for the arts in the city, and efforts to put together educational programs.

CG That emphasis is a change from the mandate of the ICA which has been to present contemporary art.

DH I think it has a lot to do with it simultaneously. To promote educational programs involving local artists. That’s not new to the ICA. In the late 1940s and 1950s with director James Plaut there were national design efforts. We were a part of national efforts in education. We were involved in Project 70 and public art projects. We developed elementary art programs around recycled materials.

Knowing that we were not going to have a building for a couple of years it seemed like a perfect time to put together an educational program.

(Hyde was working with the Mayor and particularly Deputy Mayor Katherine Kane to find a suitable home for the ICA. A long-term lease was secured for a former police department adjacent to a fire station at 955 Boylston Street. The interior was designed by the trustee Graham Gund. Initially exhibition space did not include the basement level which functioned as a restaurant. Another part of the complex was the bar Division 16 preserving the name of the former police station.)

The program would come together when we started exhibiting again. So, we could do the fund raising and planning for this program. That has been accomplished. We have raised the money and hired a staff.

CG You have now provided for educating students but what are the plans for those of us who have graduated from college? There are many who have made decisions to pursue careers in art and what is the ICA planning for them?

DH Other than education the realm of exhibitions entails outreach to the public. We deal with local artists by showing their work. We get the public to see it and own it. We are going to provide a number of jobs to local artists.

CG As teachers?

DH That’s the wrong word. I prefer mentors. Some have specific expertise and a willingness to deal with this age group. There are a lot of good artists who like to teach. This is going to make that bigger. There are a lot of artists with a social consciousness that wasn’t there before. They are concerned about education for young people.

CG What about young and emerging artists?

DH We have to pay attention to them as well.

CG What’s different?

DH We have a hell of a lot of good space which we can manage and control. We are moving into the horse barn which is a two story structure. As for exhibitions we have a lot of things in the works. The opening show in the fall will be local artists in September and October. That’s about all I can say without being specific.

There will be a show called Boston Collects Boston. Our thrust is still strong in supporting the local artists community. We have been in a bind for the past five months of not having any space.

CG When you left the ICA there was a lot of concern. Chris Cook took over for a year as director approaching the position as a conceptual work of art. There were mixed responses to that. Now you have returned. It seems that during this time the ICA has gone down, down, down. There was the fiasco of the food show at Quincy Market. (Artists were invited to use food to create art for a gala fundraiser. It devolved into a raucous food fight.)

The sense has been more of the same old jazz making it difficult to take the ICA seriously. There have been too many instances of lapse and recovery for the ICA since the 1950s. When I was in high school an annual highlight was the Boston Arts Festival on the Boston Public Gardens. In those tent shows there was always a debate about the relative merits of traditional vs progressive.

The presence of a new generation of Boston artists has existed and gotten ever stronger since the first Studio Coalition (1969) and founding of the Boston Visual Artists Union (1970). How does this new energy conflate with the vision of the reinvented ICA under your watch? Before the hiatus you were a strong ally of emerging artists. Now your focus appears to have shifted to education.

There was a lot of hope when you took over the ICA. A landmark was the Boston Now show in the new City Hall Art Gallery.

The ICA’s presence in the past two and a half years has disintegrated so what now will be different?

DH The ICA has major functions beyond exhibiting local artists. The mandate is to exhibit and educate the general public in the Boston area and New England. We have high ideals for contemporary art. One of those aspects is a strong sense of public education. Local artists are educated about art and we are reaching out to people who aren’t. We have to broaden our reach. We have to develop programs and be cognizant of as many positions as possible. We have spent the last nine months developing that. There are so many activities that have been generated in the area in the past five years. There are shows at Brandeis (Rose Art Museum) and MIT (Hayden Gallery then List), the De Cordova Museum, Danforth and Brockton museums. Taken as a whole there has been a lot of contemporary art shown in Boston that didn’t exist before.

(inaudible break)

We knew that we were going to miss this year. There were shows done that we got no credit for and had nothing to do with. Like Douglas Huebler at the MFA.

(MFA contemporary curator Ken Moffett was narrowly focused on formalism. To expand the program he invited guest curators. Chris Cook organized a show by Boston based conceptual artist Douglas Huebler.) Cook was the ICA director at the time but we never got credit for the show. (Realist curator, John Arthur presented the painter Richard Estes. For the Bicentennial Arthur, then director of the Boston University Art Gallery, organized the major traveling exhibition America 1976. It was shown at the ICA,)

CG An immediate concern is the decline or Newbury Street as a nexus for galleries.

(High rent increases were an issue and alternatives were sought. There were galleries on Congress Street near the Children’s Museum and nearby artist’s loft community on A Street. For a time, galleries opened in the leather district near Chinatown. Development forced them out. Sullivan Genovese Gallery pioneered the South End which is now the SOWA gallery district. Today, Gallery Naga and several commercial art boutiques remain on once thriving Newbury Street.)

DH That’s a reason why we are developing a new building in the Back Bay. It’s no marble palace. We are taking a super old building and renovating it. Then it will be clean and sweet with white walls. We will show as much contemporary art as possible. We are getting it through the city with an 80-year lease.

CG Do you have the money?

DH We just received the first grant for $75,000. It’s from a large Boston foundation. They fund all kinds of things including hospitals.

CG Why is there funding now when there never was before?

DH There is support from the local community as well as NY and Washington. Our history has been more down than up. There’s a chance now with a new building. Right now, we are developing very exciting programs. All of this is coming together with strong financial commitments. We are putting the institution on the map in a permanent way. The city has made a strong commitment by giving us this building. They said, ok, this is your last chance. Just do it. Pull it together. OK, give us some dough and give us some time.

CG How much do you need?

DH We’re raising a million and a half. For endowment $500,000. For the building and renovation $500,000. And $500,000 for programming.

CG What programs are you talking about?

DH There’s $100,000 for Visual Arts in High Schools. The exhibition budget will be $40,000 to $100,000 depending on how much money we can raise. The exhibition budget in the Horse Barn will be at least $40,000. That’s per year. There will be 1,500 square feet for exhibitions and 1,500 square feet for offices. That’s not a lot but it’s good space. There are 15’ ceilings. I am back here overseeing curatorial options. After (the year) of Chris Cook as director I came back as curator. We never spoke about how long that might be. He returned to Addison Gallery and decided that he wanted to do more of his own work. So, he couldn’t stay on as curator.

We hired an interim curator and did several shows including a show by “a local sculptor,” George Rogers, at the Children’s Museum. There was an Edith Halper show at the Busch Reisinger Museum. When we open our space there will be a national show as well as local shows.

(By the time the ICA left for the waterfront it occupied 6,000 sq.ft. The building is now occupied by Boston Architectural College which it is adjacent to.)

CG You did that big print show (at the Parkman House) with (curator) John Chandler. The exhibition essay became an article in Arts Canada. He said that you overruled him on aesthetic decisions.

DH I never overruled John on aesthetic decisions. The problem regarded finances. I felt greatly pressured in the realm of exhibitions because that money was always flighty money. It wasn’t foundation or government money. You just kind of went out and got the money if you were lucky. It was never a big hassle, in my mind anyway. It was problematic in that we had agreed on a budget and John went over it. I didn’t know how to pay for it and didn’t have money in the bank. Communication broke down on the financial aspects of exhibitions. I never overruled him, not even once.

The staff and trustees realized that unless the ICA found a permanent home the art scene was going to continue to be up and down with more down than up. There is a general climate. The galleries are trying to stay in business. How can you run a contemporary gallery in Boston? This became extremely apparent in late 1971. The board of trustees realized that the most valid thing we can do is to get a building. We had to drop all of our programming and rally around the main focus which was a building. We realized it would be a three-year project. It takes that long. Maybe we can do it in two. It will be fall of 1974 before everything is done.

The community is not going to die between now and then. The paid membership of the Boston Visual Artists Union (BVAU) is 500 people. There will be three new galleries within five blocks of our building. The strength of the new building, commitment, and money for programming will definitely play a role in the art scene for this part of Boston. It’s at the cross roads of the city; with a parking garage across the street, and just one block from Mass Ave. We have all the things that people care about when they come to look at and buy art. We will have one of the best restaurants in the city on the first floor. (actually lower level). We have signed a lease with Casa Romero. The subway stop is being redone. The MBTA is renovating that station. Other than Quincy Market, a major impact point for the city is Copley Square which is within walking distance.

A major show will focus on what is being done in Boston and what it collected in Boston. There is a major tie in with the MBTA in terms of their visual impact and design. There are programs to show local photography, film and video. Subway stations themselves are places for showing art. We will be a visual arts coordinator for the Bicentennial.

The ICA will be helping Kathy Kane’s office and coordinating a lot of collaborative efforts with other institutions. We had the first meeting in the Mayor’s office two weeks ago. It will pull together universities, BVAU, galleries, MFA and ICA, BCA (Boston Center for the Arts). Anyone who is doing anything was asked to that meeting. We are trying to generate the activity. After the meeting everyone was asked for their feedback. Mark Favermann was there for the BVAU. Jason Berger for Direct Vision.

We have an exciting building in a perfect location. We didn’t have that with the Parkman Building and our shows there. Location has a lot to do with this…

ICA Directors

- Nathaniel Saltonstall, (1903-1968) architect, founded Boston Museum of Modern Art, 1936- 1939 became Institute of Modern Art in 1939

- James Sachs Plaut, (1913-1996) director 1939-1942, 1946 to 1962 in 1948 renamed Institute of Contemporary Art

- Thomas Metcalf (trustee and acting co-director) 1942-1946

- G. Russell Allen (trustee and acting co-director) 1942-1946

- Thomas Messer, (1920-2013) director 1956-1962 (Soldier’s Field Road 1960-62) Then Director Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1962-1988

- Sue Thurman, (1927-2012) director 1963-1968, New England Life Hall, Newbury Street

- Andrew Cornwall Hyde, 1968-1971, 1973-1974, Died, January, 2008

- Christopher Cook, 1971-1972, a conceptual term on leave from Addison Gallery, Andover

- Sydney Roberts Rockefeller, Born 1943, acting director, 1973-1974

- Gabrielle Jepson, 1975-1978

- Stephen Prokopoff (died 2001 at 71) 1978-1982

- David Ross, 1982-1990, left to head Whitney Museum and other posts

- Milena Kalinovska, 1990-1998 later, curator of the Gwangju Biennial, from 2004 to 2015, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden as the Director of Public Programs and Education, and from 2015 to 2018 at the National Gallery Prague as the Director of Modern and Contemporary Collection.

14. Jill Medvedow, 1998 to the present

Locations

1. 1936, 114 State Street, Fogg and Busch Reisinger Museums

- 1937, 14 Newbury Street

- 1938, Boston Art Club, 270 Dartmouth Street

- 1943, 138 Newbury Street

- 1956, 230 The Fenway, second floor of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts

- 1960, 1176 Soldier’s Field Road, designed by Nathaniel Saltonstall

- 1963, 100 Newbury Street, New England Life Hall

- 1968, 1176 Soldier’s Field Road

- 1970, Parkman House, 33 Beacon Street

- 1972, 137 Newbury Street

- 1973, 955 Boylston Street, former Police Station, interior by Graham Gund, 6,000 sq. ft.

- 2006, Move to waterfront in building designed by Diller, Scofidio & Renfro, 65,000 sq. ft.

- 2018, ICA Watershed, East Boston 15,000 square foot annex.