Rusalka Re-Imagined in Chicago

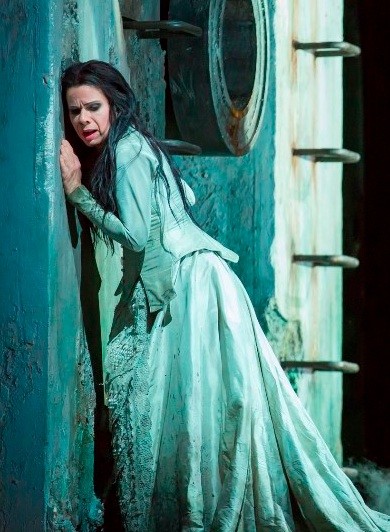

Ana Maria Martinez Captivates as Rusalka

By: Susan Hall - Mar 01, 2014

Rusalka

by Antonin DvoÅ™ák

Libretto by Jaroslav Kvapil

Lauren Snouffer (First Wood Nymph), J-Nai Bridges (Second Wood Nymph), Cynthia Hanna (Third Wood Nymph), Eric Owens (Vodnik), Ana Maria Martinez (Rusalka), Jill Grove (Ježibaba), Anthony Clark Evans (Hunter), Brandon Jovanovich (Prince), Philip Horst (Gamekeeper), Daniela Mace (Kitchen Boy), Ekaterina Gubanova (Foreign Princess).

Conducted by Andrew Davis

Directed by Sir David McVicar

Sets by John MacFarlane

Costume Designer by Moritz Junge

Choreographer Andrew George

Lyric Opera of Chicago

Chicago, Illionois

March 4, 7, 10, 16

Antonin DvoÅ™ák’s popular opera Rusalka is playing at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Sir David McVicar of the deep dark touch has directed. He worked wih one of his favorite collaborators, John McFarlane as set director, to mount a powerful new production. Is it surprising that Rusalka is having its Lyric premiere? Hardly. The Lyric's creative consultant, Renée Fleming, is one of the title role's premier interpreters.

McVicar has taken the sad fairytale seriously and looked for its deeper truths. While a love story shimmers in the midnight moon and slivers across the pond, beneath is the story of the destruction of our natural environment by humans. Like his fellow Czech Janácek in Cunning Little Vixen, DvoÅ™ák warns us and McVicar takes up the warning.

The Prince says early on, “The hunt has barely begun, but already I am exhausted. That strange magic has captured me again.” He is torn between his predatory self and his sense of the beauty of nature in the seductive form of Rusalka.

Although the adult fairytale has in the past been presented from the water nymph’s point of view, we clearly see it now as the Prince's. During the Overture, the Prince admires the framed picture of wetlands bathed in moonlight which forms the opera's curtain.

The Prince is a hunter, and the Act II main room of his castle looks like a hall at Balmoral, stuffed stag head after stuffed stag head mounted on its walls. Helen Mirren as Queen Elizabeth face to face with a stag seems to be reflected in the moon’s face.

Act II opens in an inset kitchen, boiling, steaming, roasting the dead animals. Carcasses hang from the ceiling, awaiting the banquet. So much vitality invades this scene overflowing with the consequences of man’s slaughter.

The red of the oven's fire, the blood of destruction and Ježibaba's brew puncture the grey doom of the overall set.

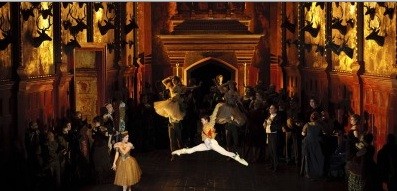

Moving into the party, originally rumored to be an announcement of the Prince's marriage to this other worldly creature, a polonaise accompanies the courtly dance. Formal and distant from passion, it is distant also from the icy nymph trying on a human soul.

Andrew George’s choreography displayed everything we are losing as we destroy nature: the joy, abundance and sensuality.

Acts I and III are marshland, now drying up because a dam has blocked their water source. McVicar and McFarlane make the point from the start; man’s hand in nature is cutting humans off from their wellspring.

The dry brittleness of the marsh, the looming dead tree trunks turning and turning as the moon passes by, bode evil. Ježibaba, the witch who lives in a strange hut accessed only by step rungs, is juicier than the other characters. Jill Grove is a superb actress, creating her character with gesture and movement as she rocks from evil doer to enchantress to a wise adviser.

There is nothing heavy-handed in this treatment. In fact, it deepens the impact of the opera. The ugliness of a marsh gone dry and even of castle walls bathed in golden light focused on dead stag heads is unavoidable.

Why should opera be left always to failed love as its message? Other topics may move us to an awakening. Time teaches that there is little we can do about love.

This was the last libretto of Jaroslav Kvapil. While non-Czech speakers can appreciate the shape of the opera and the language in translation, the many pleasures of the original language, often worthy of comparison with Shakespeare’s, is difficult to appreciate for an outsider. Kvapil uses both poetic and folk language, coloring the words the way DvoÅ™ák colors his score, weaving between lush romanticism and jovial, earthy folk.

DvoÅ™ák's operas were accused of being too symphonic. They are through-composed and like Wagner, who DvoÅ™ák admired, the arias arise from the orchestral score, the entire piece woven into a whole. Janácek commented on his long mostly silent walks with DvoÅ™ák: the man thought almost entirely in tones. Did DvoÅ™ák identify with Rusalka?

DvoÅ™ák's music is lush and in itself a plea for humans to honor nature. The references to folk tunes throughout seem to say: listen, hear what we can create when we are left to celebrate the world about us. The melodies in this opera are redolent of nature. Sir Andrew Davis conducted the gorgeous score.

Brandon Jovanovich's developed voice is now perfect for Lohengrin, Carmen and especially this role. We expect his acting and handsome presence. But the edge to the tone, the shaping of phrase and the dynamic range has become superb. He was a real treat to hear and see, successfully conveying the Prince's wish to embrace nature, even in the form of a shapeless water nymph and also his impulse to kill everything in his path.

When Jovanovich sings, “If you lips are mute, I will kiss a message from them,” we are convinced. Rusalka wants a human kiss and then bears a fatal one. There are at least 15 words for kiss in Czech and all of them are used here. The singers show the difference between a peck and the final, fatal French kiss.

Eric Owens was in beautiful voice as the Water Goblin, and enjoyed flirting with Rusalka’s sisters more than his gloomy task of abandoning the world of the waters as humans evaporate them.

Ekaterina Gubanova personified unambiguous human evil in tandem with heat. She and Jovanovich have the only duet in the opera, a concession DvoÅ™ák made, like Wagner in Tristan. It is dramatic, impassioned and foreign to the rest of the opera.

J’nai Bridges and Anthony Clark Evans from the Ryan Center were both excellent, and Lyric debuts by Daniela Mack and Philip Horst, promising. The wood nymphs trios glimmered.

Ana Maria Martinez maintained the beauty and anguish of her role throughout. Her sumptuous voice in Act I, including the aria to the moon which is this opera’s calling card, is made all the more poignant as she is transformed into an ice-cold, mute human. She pairs well with Jovanovich. Their last act tug between her kiss of death and her wish not to exact revenge is wrenching.

Sitting in the front row was Renée Fleming in bright red. She enthusiastically applauded throughout the evening and clearly passed the torch for one of her signature roles, as Martinez took her bows.

At the Lyric, this music penetrates so deeply into our soul that it is unforgettable.