Asco at Williams College Museum of Art

Where’s Gronk?

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 04, 2012

Where’s Gronk?

It was the enigma and question that emerged repeatedly during the Symposium that accompanied the exhibition Asco Elite of the Obscure a Retrospective 1972-1987 at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA). It remains on view through July 29. The exhibition is a joint project between WCMA and The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) from September 4 through December 4.

Asco. Spanish. Definition: Disgust, revolting, vomit, nausea.

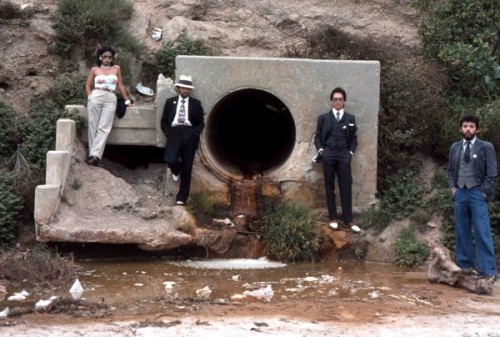

This was the initial reaction to works/ actions by four recent high school friends from East Los Angeles -Harry Gamboa, Jr., Gronk, Willie F. Herron III, and Patssi Valdez.

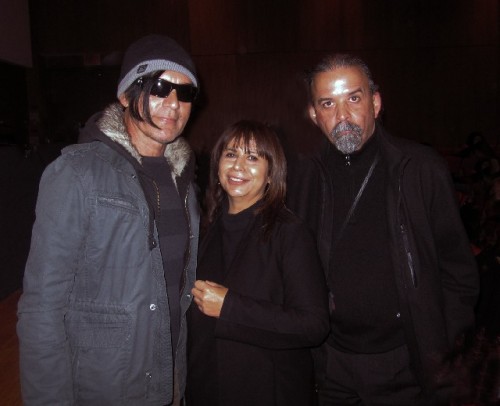

Three of the four founding artists, they attracted a number of collaborators during their fifteen years of activity, were present during this past Williams weekend that included an opening, social gatherings, and the symposium.

The absence of Gronk, it emerged during the lively and informative discussions between artists, curators and art historians, was nothing new. He proves to be the ephemeral, quixotic, spectral presence and arguably the spark plug of the group.

In the capping presentation, the anchor position of the afternoon, prior to a panel of all of the participants, art historian Amelia Jones, described a “dance” with Gronk when she attempted to engage him in a dialogue within her confining theoretical positions.

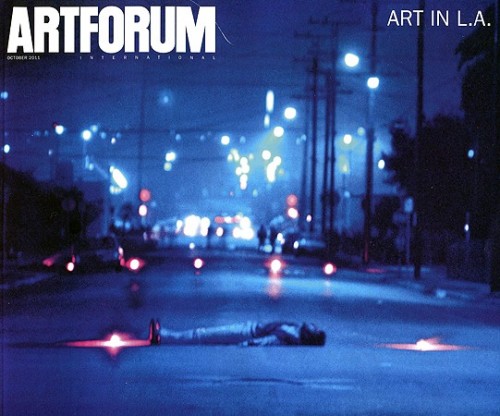

Obliquely, and with compelling photos she took during the meeting in his studio, Jones referred to him slip sliding away from direct responses to her line of questions. How one wishes that the encounter had been filmed as a document. It would reveal so much about how a spontaneous, outrageously witty, angry, wildly inventive, neo dada, ironic and poetic, of the moment group of artists are now packaged through major museum exhibitions, tomes of scholarship and, yee gads, the cover of Art Forum.

That encounter between the didactic, academic Jones and the churlish, unfettered, maverick, gonzo artist would be either a revealing document or hilarious satire. There is a thin line between scholarship and Saturday Night Live.

It begs a chicken and egg conundrum. Does the work exist prior to theory? Or from the historian's perspective does the work serve to illustrate the theory? It underscores the difference between a journalist looking for a narrative and story. Or an academic mining a primary source for the bricks and mortar of a theoretical construct.

It's what Native American activist and commentator Vine Deloria Jr. described in Custer Died for Your Sins as what happens when anthropologists sit in the sweat lodge, tape recorder and camera at the ready.

There are many layers of irony in the fact that the very museum which they tagged with their spray painted signatures would later grant them a full blown retrospective with all the trimmings. At the time they amusingly regarded their action as the world’s largest example of Chicano Conceptual Art.

In an even larger work they tagged and subverted the entire city of Los Angeles during an action and photo shoot.

Let’s play a little game.

Think Chicano.

If you are from Williamstown that may be an exotic challenge.

Now think Chicano Art.

Got it?

Perhaps you might conjure representational murals thematically focused on garishly high chroma, crudely rendered homilies of identity. Channel the strident propaganda art of the protest era of the 1970s. Are you with me?

With Asco think again. If you imagined X then they are Y. If Y they were Z.

Expect the unexpected.

It is also a reflection of a moment and its urgency.

There was risk and courage involved with spontaneous street art and actions.

During the seminar we heard Willie humorously describe how he managed to be rejected by the Draft Board during the height of the Vietnam War. One of their first actions was a channeling of intensive Catholicism a procession of a cardboard crucifix through the streets deposited at the Recruiting Station. It was a protest against the disproportional number of Chicanos and Latinos fighting for a nation which marginalized them as a people and culture.

We learned that it is illegal to photograph as they did in LA where one needs a permit. Because of the presence of Hollywood all of LA is regarded as a movie set.

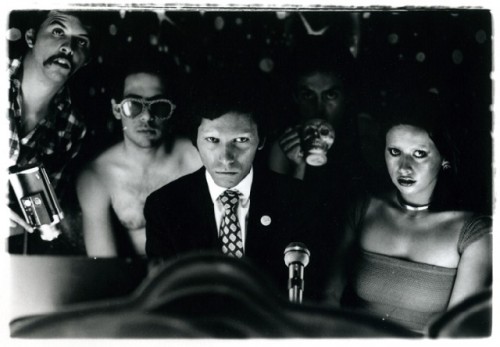

Their performance pieces, like those of the Vienna Actionists during the Post War era involved risk, illegal activity, arrest and potential brutalisation.

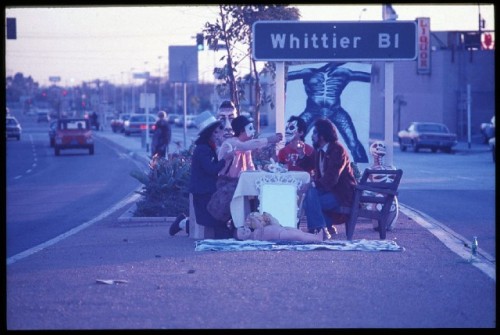

In First Supper (After a Major Riot) 1974 they staged a guerilla event on a traffic island of the main drag through LA not far from then recent riots. There is a kind of costumed dinner party, a quasi religious Last Supper/ Mad Hatter's Tea Party with props, masks, Day of the Dead makeup and a gruesome expressionist black and white painting.

As his contribution to the group Gamboa purchased a camera and 200 rolls of film. Shooting and processing slides required no skill in the darkroom or knowledge of the medium. The resultant images are low tech but of enormous archival and documentary importance. He commented that several of Asco's most iconic images were shot on a single roll of film. Because of poor archiving hundreds of slides were damaged or lost.

He was known for shooting relentlessly including pedestrians from the car window. A number of whom were later surprised when he handed them envelopes with the resultant images.

In recent work Gamboa has returned to shooting and printing black and white film. They are full length images of standing Chicanos identified by name and occupation. Their raised heads and erect posture are signifiers of pride meant to counter stereotypes.

There were references to the deadly force of the LAPD. One of the most militant and violent in America. During riots in the 1970s the police fired live ammo into the crowd. Harry described his city and neighborhood, during that era, as resembling what is currently occurring in Syria.

When a Chicano hijacked a car he was shot 60 times. The media coverage was apathetic because it was less dramatic than the guy who was plugged a hundred times the week before. There was discussion of gang violence and turf wars.

Willie described having a hurt put on him when he first arrived at Patssi’s high school. He was still associated with another rival school which he transferred from. When Patssi first noticed him in the halls she recalled him as handsome, and isolated. His face was messed up. Willie's eyebrows were shaved as a sacrifice to God in memory of his brother and for comrades in Vietnam.

It is remarkable that enough of the ephemeral material of such spontaneous actions have survived. Like the Dada movement at the Café Voltaire in Zurich during World War I nobody was looking to archive and preserve the ephemera for future generations. The material is rare and now becoming valuable.

Gamboa humorously commented that a number of works which he was certain he had deliberately destroyed ended up on the walls of the museum. Just how was not clear to him. Similarly, Herron described a process in which he and Gronk made paintings which they shredded and reassembled as a new combined work. Which they then trashed.

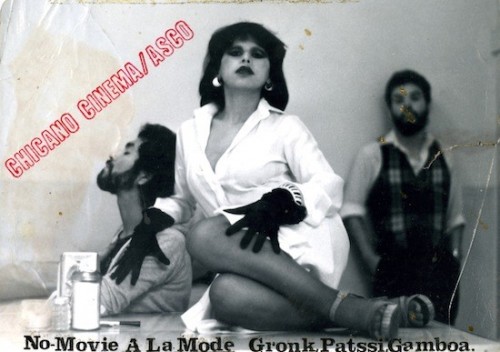

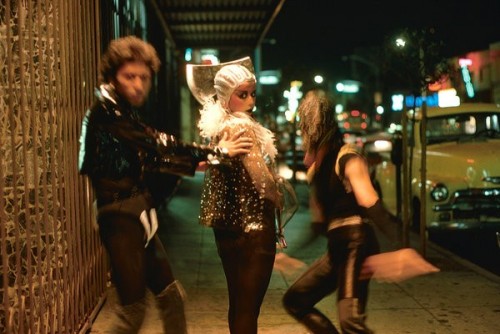

During the peak of the movement they created many graphic works, underground publications, No Movie stills and press kits, drawings, sculptures, costumes, and ersatz boutique fashions fabricated with paper and found materials.

Their associate Sean Carrillo discussed making Mariachi pants using coke bottle caps for buttons. And creating a fashion show using paper for dresses.

Poignantly, Valdez commented on how she reached the point of becoming fed up with being pissed off. She needed to find peace in her chaotic life. Under the influence of Carlos Castenada she was instructed to rid herself of her past life and to start fresh. Accordingly she destroyed much of her Asco works and focused on paintings.

Gronk, it seems, is a hoarder. Which is how much of the material survived.

During a break the artist Stephen Hannock and I spoke with Patssi. I asked if she is having success with the paintings? She was it seems until the recession. Then she had to give up her studio and is working in a garage. Although she is included in a museum retrospective she commented that no gallery appears willing to represent her. Of the Asco material she just has three collages. Which she plans to sell. Hannock suggested that she might edition them. That struck her as a good idea.

Asked “Where’s Gronk?” she suggested that he wanted to come but has a fear of flying.

Or being pinned down by art historians.

When I first visited the exhibition, frankly, I didn't know what to make of it. On many levels it seemed crude and primitive. More about documentation, history, and sociology than received notions of high art and aesthetics. It demands for one to be versed in identity aesthetics, queer culture, and contemporary normative academic/ art historical paradigms.

So this all kind of landed me on my head or buried face down in the sand.

Which is ok I guess if you get something out of the experience.

If you accept the notion that art is a journey this was quite a trip.

Like bringing the barrio to the Berkshires.

That notion of displacement is attractive. But there is also the degree of difficulty of extracting the vibrancy and urgency, the take no prisoners creative actions, from the embalming and enshrining process of museumafication. The art world loves to package the esoteric. To sift through forty year old detritus, elevate and recontextualize. The Elite of the Obscure in Art Forum.

There is a disconnect from the street were the work was created and the communities which rejected and reacted to the first generation. In the foggy netherworld of time and memory, an army of art workers methodically embalm and preserve its ephemera and palimpsests for future generations. They conflate it with theories as the detritus of the tenure industry. There’s a bit of King Kong in all of this. All the big words used to discuss simple and galvanic (there’s one) events.

What drives my curiosity is the story of three edgy Chicano guys and their Chica hanging out, dreaming up incredibly funny, insightful and clever stunts while having tons of fun. Patssi who describes herself at the time as a Mexican Hippie who liked hanging out with straight guys who were blurring gender by wearing her makeup, dying their hair, and wearing outrageous costumes. She expressed little interest in Salsa preferring Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell or making loud, fast, punkish rock by conflating English and Spanish as Los Illegals. They liked the idea that the title of their band combined Spanish, Los, and Illegals, English.

Club owners were reluctant to book the band in fear that it would attract fans that would tag the neighborhood, break into cars, and cause mayhem. By the way, some of their high school buddies, Los Lobos, are headed for Mass MoCA on April 5.

During the hippie 1970s in New York Patssi would have been a perfect Slum Goddess in the underground rag The East Village Other. While in NY she told me of being disconnected with the cool minimalism that prevailed. She was about content while the art world was then pretty vacant or camp. She described posing for "Andy Warhol's magazine but I never met Andy or was invited to any of his cool parties."

Actually Patssi you didn't need an invitation. You just crashed. Or as Woody Allen put it "80% of success in life is showing up."

In LA it was inevitable that Asco would be caught up in and influenced by the mural movment, which they initially participated in then parodied, as well as film culture. It is the city of dangerous gangs and Chicano neighborhoods but also Hollywood and Rodeo Drive. Film stars in their mansions.

The No Movie projects with their ersatz stills and press kits were seemingly inevitable. Patssi talked about wanting to wear those fabulous outfits in the fashion magazines. To dress like the stars. Willie described finding stuff in thrift shops. Creating a look and ersatz personas from the cheap castoffs, the rags and schmattas of consumer culture.

Hmm. Doesn’t that sound like Cindy Sherman and her series of black and white Movie Stills? Perhaps what separates the No Movies of Asco from Sherman’s Movie Stills is the dichotomy of West Coast Chicano and East Coast, high profile, New York Art World. It is a study in the contrast of geography, ethnicity, money and culture. LA at that time had lots of money but not much interest in contemporary art. Particularly work created by Chicanos.

So why Williams?

As we learned from keynote speaker Amalia Mesa-Bains there was a protest movement by students demanding more Latino faculty. She was an artist in residence at Williams a generation ago. The current faculty member and co curator of the exhibition, Ondine Chavoya, Associate Professor of Art and Latina/ o Studies is a direct result of that legacy.

Mesa-Bains discussed being at least a decade older than the Asco artists. She was the daughter of a farm worker near San Francisco. Her family moved from Mexico during the 1917 Revolution. She described the distinct differences between rural/ farming Chicanos and the culture of urban populations in Los Angeles. Because of issues of labor and immigration it was a well organized community astute at political protest. When two Chicanos meet it’s a conversation when three meet it’s a caucus.

While of necessity radicalized the Chicano culture is also conservative, traditional, religious, and repressive of women. Because of pressing needs she describes with regret down playing or abandoning feminist issues within the historic Chicano movement.

Patssi recalled being asked to pose for the cover of a Chicano publication. After much editorial debate it was decided that she did not represent Chicano women. Even her role within Asco was somewhat subordinated in media coverage. As she told me it was assumed that she was the pretty Chica with no brain. Hardly the case. I found her ferociously intelligent, feisty, charming and vulnerable.

So yes. This exhibition has changed me. Not that I claim to understand it. That will take more time and effort. These comments are the beginning of a process.

It is always key to acknowledge the artists. To celebrate them for their courage, invention, and commitment. They prevailed against the revulsion (Asco) of their own community and the apathy of the establishment art world which quixotically now embraces them. Particularly when it comes decades after the fact recognition and fame can be difficult to understand, absorb and cope with. It is easier to endure rejection and scorn than success.

As Mesa-Bains commented she was young when she realized that she would never be accepted as a true American. But she would also never be a Mexican.

How surreal that this dialogue and exhibition occurs while the cover of Time Magazine conveys a grid of Latinos who will decide the next election. In the bucolic Berkshires it's difficult to comprehend how this came to be.

It is a social, political, economic and cultural sea change to consider while touring this complex, daunting and fascinating exhibition.

Patssi Valdez Dialogue Part One