Calixto Bieito Brings Camino Real to Chicago

A Provocative Williams at the Goodman Theater

By: Susan Hall - Mar 06, 2012

Camino Real

by Tennessee Williams

in a new version by Calixto Bieito and Marc Rosich

Set Design Rebecca Ringst

Goodman Theater, Chicago

March 12- April 8, 2012

Camino Real started as 10 Blocks on Camino Real, and was directed by Williams' friend and collaborator, Elia Kazan. The play would be developed for seven years at the Actors Studio. On Broadway, Kazan directed. He later wrote: "..it is a beautiful love letter to the people Williams loved most, the romantics, the innocents who become victims in our business civilization. The central character is Kilroy, a one time Golden Gloves champion in this own mind, who wandering without direction over the earth, has arrived at the final, mysterious place where Death waits."

Kazan apologized for this production: "The play called for something other than realism." Kazan stated that he had not done the play justice, because he kept trying to make it real, just the opposite of WIlliams' intentioin. He admits to infusing the play with "excessive naturalism."

Realistic Camino Real is not, although it plumbs the real depths of human feelings, of eroticism unleashed and man's essental loneliness. "When so many are lonely, it would be inexcusably selfish to be lonely alone," is a line from the play.

We are in a dream setting, Williams specifies a Latin American country, a police state. The real Haiti was like this during the regimes of Papa and Bebe Duvalier. Passing through a Tonton Macoute barrier and traveling up the coast to Amenie, I spent the night in the Duvalier beach town where the central hotel had no electricity and there was only a bed pan available. Had I been killed, noone would ever have known. Dead end places in police states are like this.

Graham Greene set The Comedians in The Hotel Oloffson in Port Au Prince. Rooms there were named for guests: Greene, James Jones, Sir John Gielgud, and cartoonist Charles Addams, who mingled with ordinary people. In Camino Real, Williams named his characters after unforgetttable figures from history like Don Quixote and Casanova and mixed them with the plain people of his imagination. Williams wrote 20 years before Greene.

Malcolm Lowry found a dead end in Mexico. Cormac McCarthy's The Road and Nobelist Jose Saramago's Blindness also depict the terminal condition. Films based on these important novels show just how difficult it is to set a dead end.

Calixto Bieito takes up the challenge and succeeds remarkably, perhaps because he was born in a Spanish police state, Spain during the rule of Franco. Magic realism of Spanish culture runs in Bieito's veins and flows through Camino Real.

Bieito may be the bad boy of European opera and theater, but in this staging at Chicago's Goodman Theater, he seems more brave and visionary than bad. When Robert Falls, artistic director of the Goodman, first saw Bieito's work he was bowled over: "It was raw, vivid, illuminating and shocking."

Camino Real in Bieito's hands is a tone poem. Texturally what appears on stage is dense, eye-catching and true. Bieito moves in an hallucinatory world, backed up by a grid fence suggesting an impenetrable border, which provides the actors a chance to both try to climb for escape or to drop down to death. Innovative European theaters like Rogue Play in Birmingham use the technique. Bieito snatches music and sounds and visual grotesquery to brilliantly capture Williams' tone. Memorably, neon signs hang from the nowhere ceiling: a girl on a pole, no exit, spinning, multi faceted ball lights make the tawdry stage proceedings glitter.

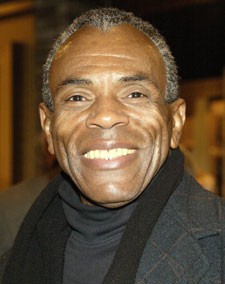

Bieito has said that he works with actors to get them to push, to dare with him. Andre De Shields (Baron de Charlus) sings a version of Screamin' Jay Hawkins "I Put A Spell on You" as he moves through luggage of street people hoping to leave when the unscheduled departure ladder-out-of -hell descends and then retracts with noone on board. De Shields takes over the stage here in the company of other stunning performers. Unlike the Proust character on whom he is based, there is no self-loathing. This is the Baron who had a man beaten for making a pass at him. Oddly De Shields also suggests the small black man who wove through the lobby of the Oloffson, a man who knew everything and would try anything. In this play, the figure is a transfixing, licentious gay man, who knows he is at the dead end.

In every performance in the preview I attended, actors were giving more than they had. Ironically, they are all trapped. Going beyond the limits when the limits are chains, police searchlights and guns, makes thrilling theater.

So much more is given by Bieito. While our dark and sordid sides are on full display, they serve to make the tender moments in which connections come tantalizingly close to realization, poignant and particularly touching. As noisy as the show is at times, these scenes are created in silence and leave the audience numb. Most of the time gross sex is the most available connection.

Don Quixote, who frames Williams' play, is dressed like Williams, and shocks, as he stumbles around with his bottle and his dreams, vomiting from time to time as he speaks. The adapters have used Williams' own words from Memoirs and other commentary. Now the omniscent Don Quixote/Williams character is the gaze of the contemporary audience, fascinated and repelled.

Bieito and his collaborator Marc Rosich take Kilroy out of the play's center, but the failed American boxer who is wandering the world expresses our central wonder at this deadly place. Signs all over the World War II fronts read: Kilroy was here. Kilroy announces that he is here. So this is where Kilroy is after he was. So too for Lord Byron, Casanova, Marguerite Gautier and common, invented people of the street. There is no exit, although a scene when the exit express arrives to provide escape has everyone clambering to get on. Everyone wants out. All fail.

This Goodman production is disturbing and engaging. It takes your eyes out of their sockets, and almost excises your heart as a heart excision actually takes place on stage. Bieito's Camino Real must be seen by anyone interested in the theater, in Williams, and in the human heart.