Il Pane Degliangeli, Offering of the Angels: Paintings and Tapestries of the Uffizi Gallery

On View at Savannah’s Telfair Museums Through March 31

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 07, 2013

Il Pane Degliangeli, Offering of the Angels: Paintings and Tapestries of the Uffizi Gallery

Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale

November 19 to April 8, 2012

James A. Michener Art Museum

Doyelstown, Pennsylvania

April 21 to August 10, 2012

Chazen Museum of Art

Madison, Wisconsin

August 24 to November 25, 2012

Telfair Museums, Jepson Center for the Arts

Savannah, Georgia

December 7 to March 31, 2013

A centerpiece of the special exhibition Il Pane Degliangeli, Offering of the Angels: Paintings and Tapestries of the Uffizi Gallery is a gallery devoted to “The Madonna and Child with Saint Catherine of Alexandria” (school of Titian) with materials and images chronicling the process of restoration and cleaning.

The resultant painting looks stunning and pristine. One can feel the breath of the master hovering over the shoulder of a studio assistant. Titian was renowned for the use of delicate layers of glaze to achieve depth and shimmering surfaces.

As a result of over zealous and less informed cleaning, mostly in the 19th century, too many of the great works of Titian were scrubbed clean and are now literally a shadow of their former selves.

In the case of this master benign neglect is preferable to misguided attention.

A case in point is Titian’s “Rape of Europa” in Boston’s Gardner Museum which was fortunately overlooked by thieves who focused on Vermeer and Rembrandt. By default, the painting is among the handful of greatest works of Italian Renaissance masterpieces in American museum collections. It was spared the devastation of a 19th century cleaning.

Titian said "Flesh was the reason that oil painting was invented."

It was protocol for museums to slap on a layer of varnish to brighten up Old Master paintings. This has a short term positive impact and a long time negative one. With age the varnish darkens and become opaque much like the cataracts that afflict the eyes of the elderly.

The normal treatment is to remove the old varnish and replace it with a fresh coat.

With Titian, however, it was not until the current state of scientific restoration, that a technician could distinguish a coat of varnish from a similar appearing delicate glaze. A standard formula for glaze medium includes one third of damar varnish, one third stand or thickened linseed oil, and a third spirits of turpentine. It was used with transparent or dye pigments which are colloids in emulsion such as alizarin crimson. Glaze medium can not be used with earth colors and opaque pigments.

While we fully appreciate and celebrate the masterful restoration of the featured painting it also serves to remind us how urgently most of the other works in this traveling exhibition are in need of similar aesthetic triage.

The magical marketing word in this traveling exhibition is Ufizzi.

It evokes the thrill of visiting the great collection in Florence.

But the works we viewed in Savannah, the last stop of four museums, were not removed from its walls. Rather they are paintings by minor masters, mostly familiar only to scholars, or lesser works by renowned artists ratcheting up the project.

To my eye the greatest single piece was a small work, parchment glued to panel, by Lorenzo Monaco (1370-1425) “Christ Crucified and the Grieving Virgin, Saint John, and Mary Magdalene.”

The painting dates to 1395-1400 a period of transition during the International Gothic from Cimabue to Giotto to the naturalism which emerged during the generation of Masaccio (1401-1427). The body of Christ on the cross is more life like and less formulaic than was usual in the Gothic manner. But the Gothic vividly prevails in the gold leaf background which was standard before Alberti invented and Masaccio introduced linear perspective.

The wide and narrow, three part panel “The Last Supper, The Agony in the Garden and The Flagellation” (ca 1510) from the workshop of Luca Signorelli (1450-1523) was absorbing and richly detailed in the lively manner of the master.

We enjoyed a lesser work by the always fascinating Mannerist Il Parmigianino (1503-1540). The modest “Madonna and Child” (1525) could use a bit of freshening up and lacked the distortions and exaggerations of full blown Mannerism but it held its own. For discerning viewers it was a nice discovery.

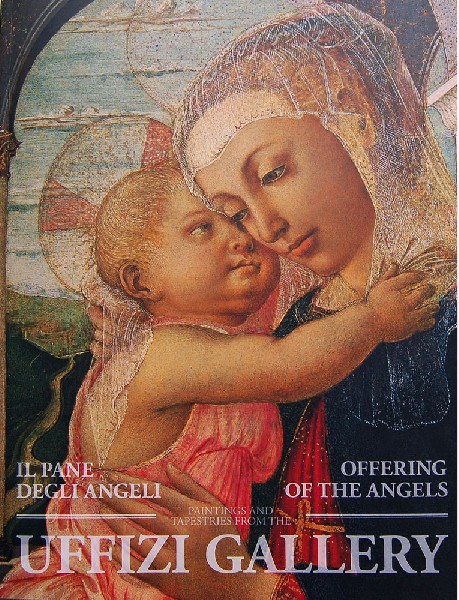

The exhibition includes a superb work by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) “The Madonna and Child” or “Madonna of the Loggia.” The image by the sensuous and often sentimental master has been used for the cover of the exhibition catalogue. Its appeal is truly universal and this single work is head and shoulders above the majority of other paintings in the traveling exhibition.

With a caveat. The credit line in the catalogue informs us that it is a painting by Botticelli (and Ninteenth Century restorer).

The practice of restoration has changed since then. The former approach was to make the painting whole and cohesive to the viewer. To fill in gaps and losses so that the surface appears seamless to the viewer. Often this was initiated by dealers intent on selling more attractive wares. A finished and cohesive Botticelli, for example, commanded a good price from rich collectors ignorant of provenance and conservation reports.

In 1957 the Guardian in London noted that Corot painted 5,000 works, of which 10,000 were in the United States. And in 1990 Time magazine let it be known that “it used to be said” that Corot painted 800 pictures in his lifetime, of which 4,000 ended up in U.S. collections.

The prevailing mantra today is that all restoration must be reversible. It allows for the progress of scholarship and advances in craft and technology.

Frequently, there is controversy following major restorations. Some art historians, for example, argued that Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos were ruined by aggressive cleaning and restoration. Particularly that the artist’s fragile layers of a secco overpainting had been removed with the general grime.

Those who knew the paintings from before the restoration recall them as dark and moody. That was the result of centuries of soot from candles, atmospheric changes as the result of up to a million visitors a year, and many touch up campaigns including swabbing on varnish and glue.

Now the ceiling is bright with brilliant color. Is that how Michelangelo painted them?

Similarly, if you visit Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris be aware that none of the Gothic sculpture is original. They were pulled down and destroyed by the idiotic mob during the French Revolution. What’s left of them is found a few blocks away at the Cluny Museum. So what we see in situ are 19th century academic imitations of the Gothic.

While studying art history at the graduate level we were told never to visit an exhibition of Old Masters without magnifying glasses. Actually, guards freak out if you get that close looking long and hard at the paintings. It helps to view the surface from an angle which reveals inpainting and inconsistencies.

Many of the works on view convey a charming but enervating sentimentality. The theme of this show focuses on angels which, for me at least, is a bit of a stretch. The nuns taught me to embrace my guardian angel but we parted company long ago.

What then to make of a perfectly lovely painting “The Nativity” by the little know master Alessandro Tiarini (1577-1668)? This exposure to the work is unlikely to inspire further exploration of his oeuvre. Similarly “The Annunciation” by Livio Mehus (1627-1691) has charm but ho hum.

While Tintoretto (1518-1594) is a great master the painting on view “The Sacrifice of Isaac” is not one of his most memorable works. It is, however, one of the most absorbing paintings in the exhibition. Looking deeply through the gloom of the darkened surface one can discern the subtle touch of the master who covered the walls of Venice with miles of paintings.

It is understandable that the four museums were delighted to host this selection of works from the Ufizzi. Significantly, no major museums participated. This is not a show that one would encounter at the Met, MFA, National Gallery, or Art Institute.

That underscores no risk taking on the part of the Ufizzi. The project appears to be about packaging works from storage to generate cold cash. There is something rather cynical about that. The participating museums deserved better works.

Shame on the Ufizzi.

Basta.

Images courtesy of the Ufizzi Gallery and the Telfair Museums.