Orpheus and Oedipus Meet at Emmanuel Music

Three Modernist Works Investigate Myths

By: David Bonetti - Mar 07, 2018

“Metamorphoses: Orpheus in Oedipus”

Matthew Aucoin, “The Orphic Moment”

John Harbison, “Symphony No. 5 for Baritone, Mezzo-soprano, and Orchestra”

Igor Stravinsky, text: Jean Cocteau, “Oedipus Rex”

Emmanuel Music Orchestra and Chorus

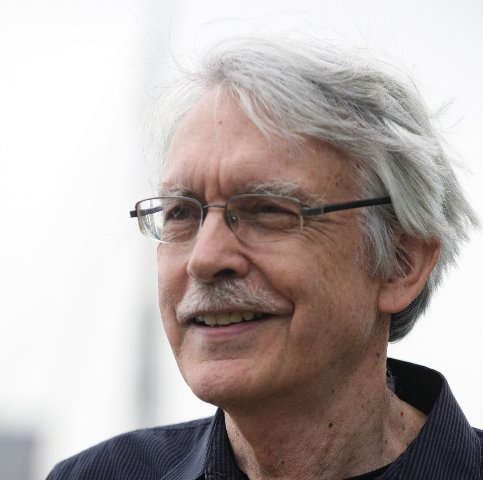

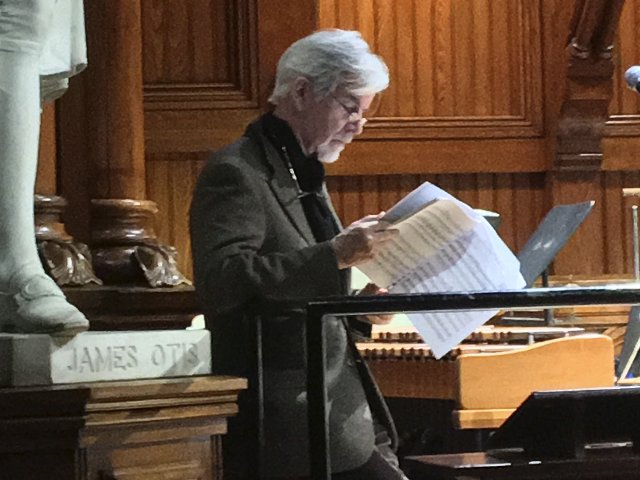

Ryan Turner, music director and conductor

Harvard Glee Club, Andrew Clark, director of choral activities

Urbanity Dance, Betsi Graves, director

Casts:

“The Orphic Moment”: Deborah Rentz-Moore, mezzo-soprano; Heather Braun-Bakken, violin; Jacob Regan, dancer

“Symphony No.5”: Krista River, mezzo-soprano; David Tinervia, baritone

“Oedipus Rex”: Jon Jurgens, tenor, Oedipus; Michelle Trainor soprano, Jocasta; David Kravitz, baritone, Creon and Messenger; David Cushing, bass, Tiresias; Matthew Anderson, tenor, Shepherd; Christopher Lydon, narrator

Sanders Theatre, Cambridge, February 23, 2018

The old days are over. No longer can a music organization throw together a bunch of pieces and call it a program just because it wants to play them. No, today, you need to have a theme to give the concert a meaning greater than the individual pieces offer. It doesn’t necessarily have to be profound or worthy of a dissertation, just some connection that holds the pieces together. The Boston Symphony Orchestra, for instance, which has been assembling programs organized by theme under music director Andris Nelsons, recently performed works by three composers, Anton Webern, Bela Bartok and Igor Stravinsky, who were born within three years of each other, thus supposedly sharing a historical connection. And soon it will present a program composed of Leonard Bernstein’s “Kaddish” and Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” symphony, their connection apparent in their titles.

Emmanuel Music’s “Metamorphoses: Orpheus in Oedipus” exemplifies the tendency, but it also suggests some of the pitfalls inherent in pairing works that don’t go together as well as they might seem at first appearance.

Artistic director, Ryan Turner, who conducted the program, attempts to link the two figures out of ancient myth by more than just the shared first letter of their names by turning to Jean Cocteau, who had something of an obsession with Orpheus, directing a trilogy of films about him. In his final treatment on the theme, “The Testament of Orpheus,” according to Turner, Cocteau plays an 18th century poet time traveling in the quest for divine wisdom. The poet says: “Of course works of art create themselves, and dreams of killing both father and mother. Of course they exist before the artist discovers them. But it’s always ‘Orpheus,’ always ‘Oedipus.’ “

Turner uses Cocteau’s poetic conceit to pair the two mythological figures in his engaging program. In fact, the two never encountered each other in the much retold versions of Greek and Roman myth. Orpheus, the fabled musician whose lyre could tame wild beasts, is a creature that appears throughout Greek myth, and his story played a seminal role in the development of opera – the very first opera, in fact, was Jacopo Peri’s “Euridice,” presented in Florence in 1600. Turner gets in trouble here by titling the entire concert “Metamorphoses,” after the compendium (in the singular) of ancient myths by the Roman poet Ovid, which feature transformation from one bodily form to another. The Orpheus myth does appear there, but Oedipus, the man who killed his father and married his mother, as immortalized in Sophocles’ play, makes only a passing appearance in Ovid’s masterpiece, in his encounter with the Sphinx. Neither Oedipus or anyone else in his patricidal and incestuous story experienced bodily change, other than, of course, death.

The connection between the Orpheus and Oedipus is forced, but it didn’t prevent the program from succeeding on musical if not thematic terms. The first half featured two works, by Matthew Aucoin and John Harbison, both of whom have local connections, that treat the ever-popular myth of Orpheus and his hapless beloved Eurydice, while the second half contained Igor Stravinsky’s great if bizarre opera-oratorio, “Oedipus Rex,” neatly separated by intermission. So the pitfalls I mentioned were not fatal, less a pothole that might destroy your auto’s axle, more a missing brick in the sidewalk around which you can easily negotiate, if you keep your eyes open.

Musically, the three works fit together well whatever their themes. All are resolutely modernist, exploiting the full resources of a modern orchestra, its unexpected and unusual colors – batteries of brass, percussion, woodwinds and even an electric guitar dominate the orchestrations. All three are rhythmically dynamic, peppered with frequent, sometimes unexpected bursts of sound that probably reflect the anxiety of modern life and the violence that has accompanied it. Turner conducted them all with vigor and athletic grace.

The concert opened with Aucoin’s “The Orphic Moment,” a curtain-raiser that set the stage for the two later works. Barely 20 minutes long, it doesn’t retell the familiar story of Orpheus and Eurydice, but serves as a commentary on it, suggesting that Orpheus intentionally looks back at Eurydice because he realizes that the loss might “inspire the greatest music ever,” thus privileging art over love.

Aucoin is the latest in a string of young composers to carry the great hopes of the classical and opera worlds to provide it with new and important works. Only 28, he grew up in Medfield and graduated from Harvard, summa cum laude. His father is the Boston Globe’s theater critic, and he is now artist-in-residence at the Los Angeles Opera, working as both composer and conductor. From the evidence of “The Orphic Moment,” the only work of his I’ve heard - I missed his opera “The Crossing,” which was premiered by the ART in Cambridge - I would say that he has a better chance of making it through the long stretch than some of the candidates championed as opera’s savior. (Yes, I am thinking of Nico Muhly.)

Rather than succumb to an easy romanticism and produce quasi-arias that aim for Puccini and fail even to reach the level of Andrew Lloyd Weber like many of his peers, Aucoin adopts a more stringent aesthetic, writing music that arises out of the text, which he also wrote, which often leads to angular and dissonant sounds, not songs. He does show his influences – especially at the start, the motivic repetitions and chug-a-chug-a rhythms of Philip Glass, certainly the greatest influence on younger composers, are all too evident.

Aucoin gives Eurydice no words to speak. Her wordless “text,” pre-or perhaps-post-language, is voiced by the violin, played expressively by Heather Braun-Bakken. Orpheus does have words, and they’re sung by richly voiced mezzo-soprano Deborah Rentz-Moore whose high tessitura is unusual in a mezzo. (The role was originally sung by Anthony Roth-Costanzo, the extraordinary countertenor.) Still the “duets” between mezzo and violin were articulate, although the case could be made that since husband and wife speak different languages, they never fully communicate.

The Emmanuel performance featured a solo male dancer the original performances lacked. His genesis was unexplained: we can only surmise whether Aucoin suggested it. In any case, he was present and rose to accept the audience’s applause. The dance was performed by Jacob Regan of Urbanity Dance and choreographed by him and Betsi Graves, the company’s director. The movement was highly athletic, gymnastic even, and Regan possessed an amazing flexibility that gave his movement an almost rubberiness as he seemed to turn himself inside out. The dance was particularly effective during a passage that featured Brazilian style drumming in the band.

The forces for what Aucoin calls a “dramatic cantata” were unusual, but the singer, the violin and the dancer, accompanied by a small chamber orchestra, came together to create a not soon-forgotten work.

Aucoin expected his audience to be familiar with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, offering only a gloss on it rather than a full-out restatement. In his Symphony No. 5 John Harbison sets a text by poet Czeslaw Milosz that retells the story, but in a truly distinctive manner. The story of how Harbison came to set Milosz’s verse and two additional poems by Louise Glück and Rainer Maria Rilke is complex. Boston’s most prominent composer, the best supported by local institutions and the most played by musical organizations across the country, Harbison was commissioned by James Levine and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, to write the symphony, not the first work of his commissioned by and premiered by the orchestra. Harbison was working on the symphony when Levine, who, according to a BSO text reprinted in the concert program, admired Harbison’s works that set words to music, suggested that he base the new work on a text. Harbison agreed. By chance he came across Milosz’s “Orpheus and Eurydice” and realized it would work with what he had written since both dealt with loss and its aftermath. Once he chose the Milosz, which told the story as most do from the point of view of Orpheus, he realized that he wanted to hear Eurydice’s voice and found the poem “Relic” by Glück. To tie both poems together and end the symphony with a unity, he chose Rilke’s well-known “Sonnet to Orpheus.”

I think that Harbison might have been better off rejecting Levine’s suggestion, but perhaps if he had the commission would have been cancelled, about which we’ll probably never know.

Ever since Beethoven ended his final symphony, the great Ninth, with a four-voiced chorus set to a poem by Schiller, symphonists have felt compelled to set texts to music in a genre that had hitherto been purely instrumental. Brahms and Sibelius resisted, and were labeled conservative as a result. Wagner ditched the concept of the symphony altogether to devote himself to opera. But others like Mahler, Shostakovich and Stravinsky wrote some of their greatest symphonies with movements incorporating texts. Still, it is a problematic hybrid. Harbison had created works before set to texts, but his symphonies were always purely instrumental.

I found the first, purely instrumental section of the symphony the most compelling of its several episodes. I’m always surprised by how much I like Harbison’s music when I actually hear it. (His conservative reputation lodges in my mind when I’m not listening to his music.) The opening section was fresh, vibrant, colorful and percussive. Indeed, Harbison, who played in jazz bands when young and maintains a love for the genre, employs an amazing battery of percussive instruments in this symphony. Look at the inventory: glockenspiel, vibraphone, cymbals, metal blocks, guiro, slapstick, concert marimba, high bell, triangle, tenor drum, maracas, high and highest claves, sandpaper blocks, large bell, tuned gongs, cowbells, snare drum, bass drum. He used them all adroitly and purposefully. Harbison was also the composer who used the electric guitar, which substitutes thrillingly for Orpheus’s lyre.

But the symphony sags once the poetry is sung. On its own Milosz’s retelling of the Orpheus myth is inventive, told in a slangy English that suggests Eliot in his looser moments. He imagines Orpheus as a character out of film noir, pulling his trench coat against the wind at the gates of Hades, automobiles spraying their headlights upon him as he tries to open the heavy glass doors to the underworld. Milosz’s is an existential Orpheus. “Unable to weep, he wept at the loss/Of the human hope for the resurrection of the dead.”

But once sung, the freshness of the words grows stale. Milosz’s verse is bracingly conversational, but set to music it becomes drab, colorless despite the color of the orchestration Harbison supplies around and behind it. Despite adding a female voice, which was more likely done for political rather than artistic reasons, the short poem by Glück and the final verses by Rilke only decenter the work without adding anything essential. The fault was not in the vocal soloists, baritone David Tinervia, who sang the words of Orpheus, and mezzo-soprano Krista River, who sang those of Eurydice, with commitment.

What to do? Harbison could revisit the symphony, eliminate the Glück and Rilke, expand the instrumental introduction, try to brighten the music he wrote for Milosz’s text and write a new instrumental conclusion on the bones of the lovely final passage he already composed. But who am I to make such a suggestion? (I am not James Levine.) In any case composers today unlike Orpheus seldom look back and leave their compositions, successful or not, as they are as they move on to new challenges.

After intermission, we got what we came for, no disrespect of either Aucoin and Harbison intended – Igor Stravinsky’s masterpiece from 1926/27, “Oedipus Rex,” most likely the only opera you’ll ever hear sung in Latin. From the first dissonant chords, played percussively by the horns, you know you’re in Stravinsky’s world. Whatever their style - romantic/folkloric, expressionist, neo-classical or serial - Stravinsky’s works always sound like his and despite his great influence on subsequent composers, no one else quite sounds like him either. In their avoidance of traditional forms and their use of percussion, orchestral color and dissonance both Aucoin and Harbison are among the children of Stravinsky.

Although he set a few dramatic texts to music, the most traditional in form, “The Rake’s Progress” of 1951, Stravinsky is not known as an opera composer. Although he wanted to compose an opera when he set out to set an ancient myth to music, what he ended up with, according to his own terms, is an “opera-oratorio.” Such hybrids have existed, particularly in the Baroque era, but by 1926 their time seems to have passed, and Stravinsky’s choice to retell the story of Oedipus Rex in Latin guaranteed that his opera-oratorio would be not only one of the most distinctive pieces of the period, but one of the most distinctive works in his oeuvre. (The only other piece by him I know of that produces the same effect is “Les Noces” with its four percussive pianos and caterwauling sopranos.)

‘Why Latin?’ Is generally the first question opera lovers ask about the work. Stravinsky wrote, according to the program, that “The choice had the great advantage of giving me a medium not dead but turned to stone and so monumentalized as to have become immune from all risk of vulgarization.” For a composer who avoided emotional expression as much as possible – emotion being another source of vulgarization - the use of Latin also served as a distancing device. In the cosmopolitan circles Stravinsky inhabited, opera in Italian, French, German or Russian might find members of the audience easily following the action, but even though most of those members of a trans-Euro culture that is now gone studied Latin, how many of them could rustle up their memories of Cicero to deal with Jean Cocteau’s contemporary Latin text?

To give the audience a clue as to what was happening Cocteau suggested that a narrator explain, in the language of the audience, what was to take place in each of the six scenes. Stravinsky later came to hate these spoken passages, but they serve a formal purpose that only strengthens the work. In addition to reminding the audience of what’s happening in the Sophoclean drama, they function like little intermissions between the extreme expressionism of Stravinsky’s score. Without them the work might be too intense to endure.

Although “Oedipus Rex” was intended to be an acted theater work – it was written for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes - it is most often presented, as Emmanuel Music did, as a concert piece, an oratorio. There is a DVD of a performance by the Saito Kinen Orchestra led by Seiji Osawa in a production by Julie Taymor with Jessye Norman and Philip Landridge as vocal soloists that is electrifying, but a purely musical performance should be electrifying as well, which Emmanuel Music’s proved to be.

Turner led the orchestra like a cudgel, hammering out the propulsive rhythms of the opening chords, played by a battery of percussive horns, to turn on a dime to produce the sweet, lyric tones that accompany the vocalists, especially notable in Jocasta’s monologue. The vocal cast was at one with Turner’s vision. The only element that was not quite right was the chorus, sung by Harvard’s venerable Glee Club, its delivery of the percussive score lacking the necessary crispness.

As Oedipus, tenor Jon Jurgens made a very strong impression. Jurgens, a young singer who has appeared in local productions for the past few seasons, most notably as Tristan in the Boston Lyric Opera’s “The Love Potion” by Frank Martin, turned in the most powerful performance I’ve yet heard from him. He delivered his largely declamatory vocal lines with a plangent lyricism, singing with a powerful lower voice and a sweet falsetto when necessary.

As Jocasta, soprano Michelle Trainor, a local singer affiliated with the BLO, turned in the best performance I’ve yet heard from her. Trainor has a big voice of a type not heard much among local singers who cultivate the more delicate styles of the 17th century. One can imagine her burning up the stage in a Verdian or even Wagnerian work. Who will give her that chance? Here she made a sympathetic Jocasta, discovering slowly that her new husband not only killed her husband, the King, but is also her son by the King. At her entry the chorus has one of its spectacular outbursts, “Glory to Queen Jocasta!” And Trainor totally nailed her own balancing outburst, “Laius died at the crossroads,” when she begins to figure out what happened.

The duet between Trainor and Jurgens, “I am afraid, Jocasta, I am afraid,” and her ineffective consoling words, “The oracles lie; the oracles always lie,” was an emotional highlight of the work. But the true emotional highlight of a work that intended to avoid emotion comes at the end when the Messenger announces that Jocasta has hanged herself (“The divine Jocasta is dead”). and Oedipus reveals himself with his eyes put out, and the chorus shouts out its lament.

Jurgens and Trainor were backed up by an able supporting cast. Baritone David Kravitz sang both Creon and the Messenger with his usual seriousness. Bass David Cushing as Tiresias and tenor Matthew Anderson as the Shepherd did the most with the little they are given. A special word of praise to Christopher Lydon, who served as the Narrator. Lydon, who is familiar to listeners of both WGBH and WBUR, delivered the narration with the assurance of a newscaster. He compared very well indeed to the unctuousness of Frank Langella, who narrated the work in 2000 at the BSO in James Levine’s last performance here as its music director.