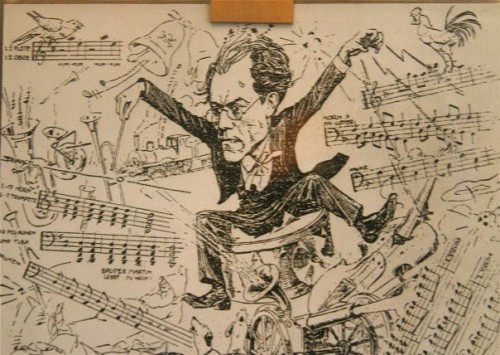

The Boston Symphony Conducted by Christoph Eschenbach

A Carnegie Triumph

By: Susan Hall - Mar 09, 2012

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Christoph Eschenbach, Conductor

Cedric Tiberghein, Piano

Hector Berlioz, Overture to Benvenuto Cellini

Maurice Ravel, Piano Concerto in G Major

Hector Berlioz, Symphony Fantastique

Carnegie Hall

New York

March 7, 2012

The Berlioz’ Benvenuto Cellini overture opened an exciting French program. While the opera that follows failed, despite strong arguments promoting a bold Berlioz, successor to Gluck in the struggle to prevent an Italian-style takeover, the Overture has always been well received. The Boston Symphony under conductor Eschenbach teamed to show us why. A surprise, full of rhythms going every which way and ah-ha entrances, the nimble performance was a delightful prelude to the Ravel Piano Concerto in G.

Eschenbach has his favorites. He single-handedly promoted Lang Lang’s career in this country, and his picks are well chosen and welcome. Tonight he brought young French pianist Cedric Tiberghein to play the Ravel with the Symphony. The piece is a duet between orchestra, particularly sections of the orchestra, and the soloist. All parties made the most of the opportunity.

Ravel had mixed muses. The spirit of Mozart and Saint-Saens, but also Stravinsky and Gershwin together with elements of Basque and Spanish music were beautifully revealed by Tieberghein.

In the first movement, Eschenbach was astoundingly vigorous, bringing forth a hard, energetic harmonic climate imposed on melodic lines. Yet the delicacy of the lines was clear in the pianist’s hands.

Jazz melodies from the orchestra are interrupted by the pianist. Solos for the piccolo and trumpet become a lively romp. Cadenzas for the harp and then woodwinds sounding harp like are followed by the more traditional piano solo. Bolero is echoed in descending major and minor triads. A poetic dialogue between the English horn and the piano and a parting allusion in muted strings were subtly suggested. A thick mix revealed with stunning clarity.

In the quiet Second movement, Tiberghein displayed a soft, yet chiming tone for the music that Ravel modeled on the larghetto of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet. In his hands, the Adagio is a song whose calm contemplation brings it close to Faure’s musings.

Eschenbach carved rhythmic verve and jazz effects in the outer movements which stood in sharp contrast to the poise and serenity of the second movement.

The third movement begins with an initial drum roll and fanfare are like the circus movement of Stravinsky’s Petruska. A piercing train whistle, folk music syncopated precede a boisterous march. The development section was a marvel, with strings and bassoons sharing fleet passagework. A chase goaded by galloping fanfares was not to be halted by the nasal tattoo of jazz. The violent struggle between meter and rhythm, a beautiful tonal testament.

Eschenbach may be an emotional specialist, but the final movement of the concerto was also full of clarity and wit.

Tiberghein played Debussy as an encore, and brought the Sunken Cathedral of Ys out of the water, and submerged it again with a delicate and yet magisterial grace. Stillness followed the cathedral’s disappearance and then the Hall burst into appreciative applause.

The Symphony Fantastique was just that. Closing your eyes, Gustav Mahler could have been at the podium a hundred years ago, leading an orchestra up to a frenzied pitch in the 4th and 5th movements. Eschenbach is like Paderewski performing a Liszt rhapsody.

When Eschenbach wanted to, he slowed things down. Oboist Mark McEwen plays two versions of a melody in the pastoral movement. The first appearance was performed tenderly and with joy. Its second appearance was almost painfully slow and wrenching. The entire piece, something of a warhorse, was reimagined and shocking again, as it should be.

The strings of the Boston Symphony sound as one, a truly remarkable achievement, which suggests an ensemble of such high caliber that they deserve the finest music director.

Certainly at Carnegie Eschenbach looked like a Muti-70, a man who could go on conducting for decades. He worked without a score, but gave detailed colorings and firm tempi. His reputation is mixed, but in Washington, where he now leads the National Symphony, he has been welcomed. Together the Symphony and conductor produced a great evening at Carnegie. They will be teamed again at Tanglewood this summer.