Tanzania: Part One

Kilimanjaro Foothills

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 12, 2012

My annual winter getaway and birthday celebration took me to Tanzania in February. On a sunny day with Boston weather in the mid-40s F, I made my way to the airport on public transportation after taking the second dose of my weekly malaria pill. The unusually mild winter day set my mind at ease regarding the connection in Amsterdam with a two-hour layover for Kilimanjaro. Due to a light-weight duffel bag on wheels plus a small carry-on, and nothing to empty out of my pockets, check-in and security clearance were fast and smooth.

The KLM flight left at 6:30 pm. Following the meal service I settled down with my book, Out of Africa by Isak Dinesen (the Baroness Blixen), who managed a coffee plantation in Kenya in the early 1900s. Her re-creation of the African landscape and the ways of the land and its people grounded my expectations of eastern Africa, knowing change comes slowly to tribal communities.

As we approached Amsterdam, the pilot announced 30-degree F weather. An unusually severe winter had gripped the city, even freezing its canals. We landed at 7:40 am local time due to the six-hour time difference between the two cities. In addition to the four layers of clothing I had started out with, including a sweater and jacket, I wrapped myself in a blanket for the second leg of the trip. The plane was packed by northern Europeans as well as Americans, identifiable by their easy-pack travel clothes. The flight offered amenities such as individual TV monitors and the option of ordering a-la-carte with a choice of Japanese or Italian menus. Sleeping part of the way during the eight-hour flight, I woke up feeling the warm air as we approached Egypt, prompting me to begin shedding my layers.

Adjusting my watch by another two hours after Amsterdam, I ended the 18-hour journey from home at 8:30 pm local time. Our trip leader, Ridas, a tall portly man, welcomed us to his country with a big smile as eight of us, mostly meeting one another for the first time, congregated around him. We filed onto a waiting bus; the outside air at 84 degrees F felt wonderful.

Arusha, a major town with a population of one million in the northeast of Tanzania, was our destination for the night. The hour-long trip into town took us on a dark road lined with single-story small houses and shops, each identified by one neon light out front. The wood smell from carpentry shops mixed with diesel fumes in the air. We arrived at the Olasiti Lodge, situated in the industrial part of Arusha along the road to Masai land, our destination the following morning. A security guard unlocked the gate upon a call from Ridas. The main lodge with an impressive cantilevered wood ceiling was a stark contrast to the visible poverty outside. “Jambo” (“hello” in Kiswahili), said a smiling member of the house staff, motioning me to follow him to my private lodge. As soon as he unfurled the mosquito netting over the canopied bed and left, I dropped off to sleep.

In the morning I strolled through lush green gardens surrounding the brightly painted guest houses, and admired tropical flowers by a pool along with thorn trees, called olasiti, the Masai word the lodge is named after. Breakfast featured an omelet station with fresh vegetables grown on site. Heading out to the Kilimanjaro foothills in two 4x4 vehicles, we passed by vendors with their wares spread out by the roadside and traveled over rough, unpaved roads made worse by heavy rains. Dodging the dust showers raised by passing vehicles and stopping for glimpses of Mount Kilimanjaro’s 19,340-foot-high peak beyond the clouds, we reached the Kambiya Tembo camp site in Sinya three hours later.

A Masai man in traditional shuka (a large piece of cloth worn like a toga) met us with a tray of cold tropical juice. This welcoming treat was much appreciated, considering the hot and dusty ride we had had. As I sipped my juice, I was struck by the unusual ear lobes of Masai men. The lobes had such big holes that I could literally see the sky through them. Apparently these elongated lobes are beauty marks for both men and women. Cut and stretched at a young age, they serve as receptacles for heavy ornaments.

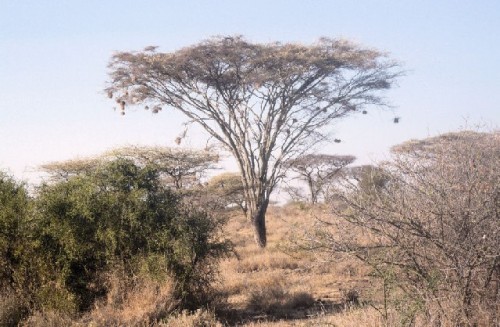

Tranquility permeated the rustic camp, our home for two nights. Flat-top acacias, known as “umbrella trees,” provided natural landscaping around the thatched-roof huts. Lunch was typical gali (polenta), served at most meals, in addition to red beans, spaghetti with meat sauce or cheese, and watermelon for dessert. Bush camps are considered hardship posts by safari concessions, so that only men are recruited to work, while women stay back in the village.

Following rest time we set out on a late-afternoon walk with our Masai guide. Walking sticks in hand, we tracked giraffe and zebra tracks, which led us to the animals, then came upon a zebra skull picked clean by vultures. We identified plants used for medicinal purposes, including thorny ones boiled and given to children for upset stomach. Inadvertently I brushed against a thorny plant and scratched my arm. The guide treated the scratch with sap oozing from a tree. The bleeding stopped instantly; the sap turned into a white chalky powder as it dried on my skin.

The next day we got up at 5:30 am for a game-viewing drive. Dressed in layers for the morning chill, we set out for the plains. Weaver nests on trees hung like ornaments, silhouetted against the dawn. A wealth of bird sounds filled the air; kori birds distinguished themselves by their calls, while warblers enjoyed the savannah woodlands. Clanging cow bells heralded approaching herds led by young Masai herders. With daybreak we began spotting animals; a vervet (green) monkey on a tree, giraffes grazing on leaves, zebras crossing the plain in single file, and elephants cozying up by an acacia, rubbing trunks to show their love for one another.

Following breakfast back at camp, we visited a Masai village. The Masai, once feared as warriors, are pastoralists leading a semi-nomadic life; men move large herds in search of water, while women and children stay behind. They practice polygamy and live in a boma of round huts built from branches and finished with hay on the roof. Each wife lives in a separate hut with her children. At age seven the children move out; boys sleep together in one hut, girls in another. Boys become herders; girls take care of babies, collect wood, fetch water, and do beadwork.

Both men and women are circumcised. While this rite of passage is optional, it is the only way for young people to learn the ways of the Masai (recognizing plants, herding, and protecting cows) from elders over a three-month training period. Those in training wear black and paint their faces in order not to be recognized. Although female circumcision is against the law, women undergo the ritual secretly because of its high tribal value.

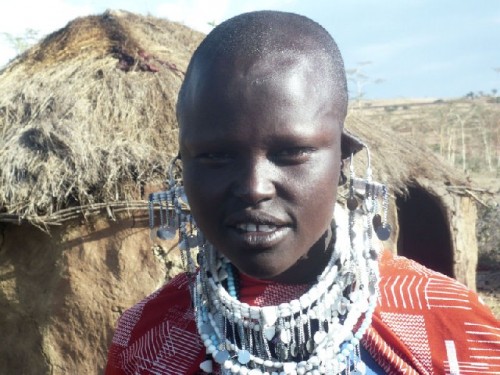

Striking tall, dark-skinned women with shaven heads, wrapped in colorful shukas, adorned with layers of chunky beaded jewelry, and carrying bundled babies on their backs, welcomed us with smiles and handshakes along with their many barefoot children. They clapped as they sang for us, while black flies hovered above, trying to land on someone at every opportunity. Some of the children had skin sores, and the smut from their noses was an added attraction for the flies.

Visiting one woman’s hut enhanced the heartbreak. A bed made of sturdy acacia branches with a cow skin “mattress” occupied one corner of the single-room hut she had built. Clothes lay in small piles on the corners of the bed. Seven cups, one per child, hung from nails on one of the wooden posts. A narrow section partitioned off with thin branches constituted the kitchen. She sat on her bed, beautifully adorned and proud, while we completed our brief tour.

The lifestyle of the Masai does not reflect their wealth, which is all invested in cattle. The more cows a man has, the wealthier he is. One cow is worth around $400-500. When a woman marries, she receives a minimum of three cows as a dowry from the husband’s family. This is one society where baby girls are valued more than boys, as girls are a source of future wealth. In the eyes of the Masai, Western women go for very little, with no wealth invested in their marriage.

The cows, sent by Enkai (God), live in the boma when they are not in pasture. They are milked in a communal open area surrounded by the huts, which explains part of the attraction for flies. In a land where water can only be obtained by traveling long distances, shaving heads is one way to keep clean, in addition to being a sign of beauty for women. Over the years missionaries have made inroads into some of the Masai villages, bringing sanitation, education, and Christianity with them. Tribal traditions still uphold the strength and endurance of the social fabric. Our trip leader, Ridas, a Lutheran, grew up in a boma with Christian parents. Although he lives in Arusha now, his cows are tended by his brother in the village. In return Ridas cares for his brother’s two children, so that they may attend private school in the city.

At the end of our visit the women spread their crafts on the ground, hoping to entice us to buy. I purchased a Masai choker, a small basket with lid and strap, and a baby giraffe fashioned out of beaded wire.

On our final day we went for another early game drive. Birds emerged at dawn; the early light was milky and soft as the sun came up from behind Kilimanjaro, which means “big mountain” in the Chaga language. A male kori bird moved slowly across the field, displaying to attract a mate by inflating his neck pouch and extending his wings. We rode through the savannah woodlands as Masai men in bright shukas worked on the bumpy roads with hand tools. We spotted gazelles, yellow baboons, and elegant kori bustards with short crests projecting from the rear of their crowns. A large cattle herd, all belonging to one boma, headed toward a watering hole along with wildebeest and zebras, the latter generating a dust storm as they ran. We too walked down to the water’s edge, where storks, lost in their own world, searched for food with their long beaks.

Returning to camp, we bid the staff goodbye and drove back to Arusha with a couple of stops along the way. The Saturday market was a busy place with large crowds both buying and selling, while idle youth hung about. Goods ranged from produce to grains, and included small dried fish sprinkled on dishes as a source of protein. Western-style clothes, such as jeans and T-shirts, vied with African fabrics, shaped into cone-like displays on the ground. Displays of shoes, including old ones, occupied a major section of the market. Ridas urged us to keep walking and not to buy anything, lest we be surrounded by a large crowd of onlookers. Stopping briefly at a sports bar, where fans were watching a national soccer game, we continued on our way.

Ridas invited us to visit his wife and children on our way into town. We were delighted at this opportunity to see a city dwelling and to meet Ridas’s family. Negotiating narrow rutted roads, he pulled up in front of an ornate iron gate. Upon his calling, his wife arrived with two little girls in tow to let us into the driveway, leading us to another world. Since bank loans are hard to come by, it had taken Ridas several years to build this house, relying on his own earnings.

The spacious house opened through an arched doorway into the living-room, which connected similarly to a formal dining-room. The only visible African accent in the house, otherwise furnished in Western style, was a living-room rug with a leopard-skin pattern. A picture on the wall with the bride in a white wedding gown revealed this to be a Christian household. We enjoyed looking at a wedding album, which displayed photos of the groom’s family in traditional Masai dress. The bride belonged to the Chaga ethnic group, and had had to be accepted into the groom’s tribe through a separate ceremony prior to the wedding.

A large chicken coop at the back of the house underscored the family’s entrepreneurial spirit. In this venture, primarily run by the wife, chickens were ready for the market in six weeks from incubation. Selling frozen whole birds at $6.50 each, the family was a major supplier for hotels.

Back in the luxurious setting of the Olasiti Lodge for one night, we looked forward to meeting the other members of our group and to starting our main trip, Safari Serengeti, the following day. In three days we had already seen and experienced a great deal, and knew that much more was yet to come.