Handel's Agrippina by Boston Lyric Opera

Hilarious Decadence and Depravity in Nero's Rome

By: David Bonetti - Mar 13, 2011

Agrippina

by George Frideric Handel

Boston Lyric Opera

The Shubert Theater,

265 Tremont St.

Additional performances March 13, 16, 18, 20 and 22

Tickets: 888-348-9738 or www.blo.org

Rome during the age of Nero was a time of depravity, early 18th century Venice was an era of decadence, and our own present is one of corruption and cynicism. Put them together, and the chances are better than not that a contemporary production of George Frideric Handel’s comic opera “Agrippina,” which premiered in Venice in 1709 and concerns the shenanigans of a young Nero and his ambitious mother, the lady of the title, is going to be a hit.

And it is. Of course it helps that the music is by Handel, one of the greatest artists of any age to set words to music.

And it is essential that the cast of singers be endowed with fluency, flexibility and sweetness of voice - and the cast assembled by Boston Lyric Opera Friday night for the most part was. A production that is stylish, even chic, and quick to play on rapid emotional changes from comedy to pathos, like this “Agrippina,” is a decided plus.

In short, the Boston Lyric Opera production of “Agrippina,” originally mounted at Glimmerglass Opera in 2001, was just about ideal, as ideal as you can hope for in the real world of opera, where more often than not the best intentions end in disappointment if not heartbreak. I loved it; the audience seemed to love it. I’d love to see it again. I recommend it especially to anyone who has given up at having a good time at the opera. It’s fun, but it’s also serious. Remember: it deals with depravity, decadence, corruption and cynicism. With a smile.

The story, which is set in first century Rome, is based on actual people and actual events. It opens with the power-hungry Agrippina scheming to get her degenerate son Nero proclaimed the successor to her husband Claudio as Emperor. When the news arrives that Claudio has died at sea, she sees victory and maneuvers to get Nero crowned. But unexpectedly, Claudio enters: it turns out that the news was false. For the rest of the opera Agrippina uses her wits to achieve her goal.

Sex is central to her campaign and you could mistake the opera at certain moments as a Feydeau farce as would-be lovers hide behind screens and under beds. The object of their desire is not the unalluring Agrippina (ambitious people are seldom really sexually attractive), but the young Poppea, a real minx who seems to have enthralled half of Rome, including the Emperor, Ottone, the soldier who saved him, and Nero. It all improbably turns out happily: Nero is proclaimed Emperor-designate, Ottone and Poppea are married and Claudio and Agrippina are reconciled. And as the cast sings the expected final anthem to Rome and its happiness, the surtitles remind the audience of that fact that the mad Nero will do them all in one by one after the curtain falls.

Music comes first in any Handel opera, and the music here was generally excellent. The orchestra, conducted by Gary Thor Wedow, played idiomatically and with real verve. Wedow understands baroque style from his association with the Handel and Haydn Society, and he raised the orchestra in the pit to be more in communion with the singers, and he created a five-member continuo band to accompany the recitatives.

Handel favored songbirds and there’s nothing wrong with that. (He practiced “bel canto” before the fact.) Basing his vocal writing on Italian precedents (Monteverdi, Scarlatti and Cavalli), he wrote arias that test singers and delight audiences. His best vocal writing was for high voices – sopranos and castrati, the male singers who were castrated to keep their voices high. (Today countertenors, men who sing in falsetto, or mezzo-sopranos take on castrato roles.) The cast of eight featured two sopranos and three – count’em, three! – countertenors. A generation ago a single countertenor was a novelty. Today they are in abundance. The three low voices – basses and baritones – although essential for the sonic mix, were odd men out.

As Agrippina, soprano Caroline Worra was fine. She acted with great comic timing. In her scheming – and in her frustration when her plans went awry - I thought of Lucille Ball more than once. She understands baroque style, and her trill is something to treasure. But her voice lacks ravishment. She was unable, alas, to put over the single greatest aria in the score, “Pensieri, voi mi tormentate,” a rare moment of reflection that her plans may backfire, with the vocal beauty it demands. It opens high but requires a full voice, Unfortunately, Worra’s high notes are thin if accurate. Although she played the “Pensieri” scene with high drama, she is a more convincing comic actress and singer.

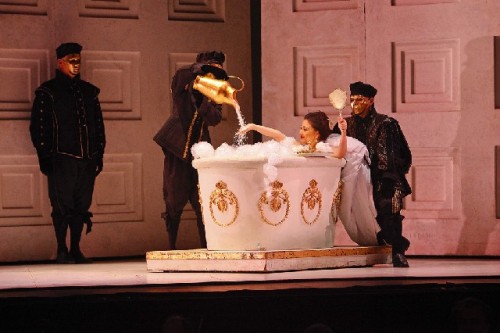

Soprano Kathleen Kim as Poppea stole the show. Vocally, the role fitted her like a glove. And Kim, who recently received rave reviews as Chiang Ch’ing (Mme. Mao tse-tung) in “Nixon in China” at the Met, revealed herself here to be a great comic actress. From her “entrance” in a gold-embossed bathtub trying on jewels and pearl necklaces and singing how much she loves such emblems of wealth, you know that this is a material girl who will marry whoever’s purse is fullest.

One of the visually most striking scenes is of Poppea at her country house lounging on a lemon-green chaise and having a slave apply her suntan lotion. (We know we are in the country because the slaves, all dressed in black and wearing gold masks, carried in a large painting of a tree and sky, and the lighting went up to super-bright.) Her funniest scene, however, occurs when Agrippina and she are having a session of girl-talk. Agrippina gives her too much to drink and her portrayal of a young woman getting drunker and drunker is hilarious. In general, Kim’s pouts, frowns and false displays of innocence are spot on. And she does it all while singing with a clear pure soprano that hits those high notes effortlessly. And she can turn from vixen to victim on a dime. I haven’t seen her in other roles, but on the basis of this performance I can say that Kim was born to play Poppea.

Poor crazy unhappy Nero is perfectly realized by countertenor David Trudgen. From his first appearance he makes you realize that he is a damaged, abused child. He plays Russian roulette with his mother’s pistol, he flicks his lighter on and off like an arsonist (foreshadowing the burning Rome?), and he shows an unnatural familiarity with his mother’s body. (Incest wasn’t frowned upon by the ancient Romans – it kept money and power in the family.)

Later he is shown to be a martini-swilling, cocaine-sniffing basket case: yet he is the man who would be Emperor. Trudgen uses his fleshy body to his advantage in his portrayal of the ultimate mama’s boy, and when he first sings, his high countertenor, coupled with his corpulence and his incestuous connection with his mother combine to create an image and a sound of nature assaulted and deformed. (I heard a few nervous laughs in the audience.) Trudgen, who possesses a richly colored instrument, deserves praise for the courage it required to play the role the way he does.

And then there is Anthony Roth Costanzo as Ottone, the only honest man in the opera. Demonstrating that all countertenors are no more alike than all sopranos are, he offered a perfect counterpoint to Trudgen. His high, pure, supremely sweet voice was swoon worthy. There were moments, like in the aria “Tacero,” – “I will be quiet” – where his voice seemed to vanish into the atmosphere. I have rarely heard an audience so still as he sang. He gave us reason to keep coming to opera.

The other singers, David McFerrin as Pallante and Jose Alvarez as Narciso, who essentially played clowns out of the commedia dell’ arte tradition; David M. Cushing as the servant Lesbo (was that intended as a joke?); and Christian Van Horn as Emperor Claudio, did their jobs well, but were overshadowed by the other, for the most part high-voiced singers. Van Horn deserves praise however for gamely playing the Emperor as a clueless man in power who has no idea what’s going on. Whenever he appeared, usually slowly taking off his clothes in order to show how sexy he was, the audience laughed as they were supposed to. Think of any world “leaders,” present or past, “gittin’ it on” - Bill Clinton and Paula Jones? - and you know what I mean.

The production team made it all work. Those who defend the Boston curse of “concert” operas should see it to understand what they’re missing.

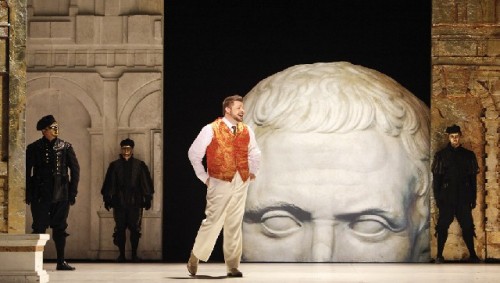

John Conklin’s sets were simple and abstract. Three massive blocks faced with Roman and Italian baroque architectural imagery were moved from scene to scene to create the appropriate environment. Heads of Nero taken from idealized Roman portrait busts appeared in different scales in different scenes. Conklin’s basic set proved highly adaptable. The scene in Poppea’s country house, for instance, was effectively created with the large landscape painting and the brighter lighting. Lighting director Robert Wierzel’s decisions always contributed to creating the proper mood. In the country house scene, as Ottone sings a meditative aria by a body of water, the stage lighting darkens and flickers the way light reflected off water does.

Conklin’s set is basically white for the Roman architecture and gold for the baroque facades. Costume director Jess Goldstein adds the color. Agrippina’s black widow’s weeds, her scarlet gown and Poppea’s coquettish outfits – the lemon-green high heels that match her chaise, for instance - both help define character and add color highlights to the monochrome set. Goldstein’s most memorable work, however, are the costumes he devised for poor Nero. Whether in a white suit that only emphasized his girth or a pair of boxer shorts with red hearts, his outfits served to underscore his bodily discomfit.

The greatest praise goes to stage director Lillian Groag. Granted, she had a willing cast to work with, but she seemed to have micro-directed every stance, gesture, grimace and double take to great effect. She might be guilty of having choreographed a pratfall too many, but she made the action of the comedy work from moment to moment with the precision of a watchmaker. One hopes that Boston Lyric brings her back in the future.