Red by John Logan

Alfred Molina and Eddie Redmayne in Rothko Drama

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 14, 2010

RedBy John Logan

Directed by Michael Grandage

Sets and Costumes, Christopher Dram; Lighting, Neil Austin; Composer, Adam Cork;

Donmar Executive Producer, James Bierman; Casting, Anne Mc Nulty; Press, Bouneau/ Bryan-Brown; Production Stage Manager, Arthur Gaffin. A Donmar Warehouse Production

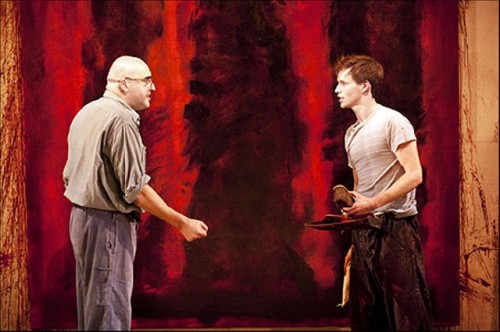

Cast: Alfred Molina (Mark Rothko), Eddie Redmayne (Ken).

Golden Theatre

252 West 45th Street

New York, NY 10036

Plays and films about artists are problematic. The less you know about the artist the more effective they are. The tendency is to focus on the persona and social eccentricity of the artist rather than an exploration of the work. It can be agonizing if you know something about art history. Recall Charles Laughton portraying Rembrandt, Charlton Heston as Michelangelo, Kirk Douglas as Vincent van Gogh and Anthony Quinn as Paul Gauguin, or more recently Ed Harris channeling Jackson Pollock or Anthony Hopkins portraying Picasso.

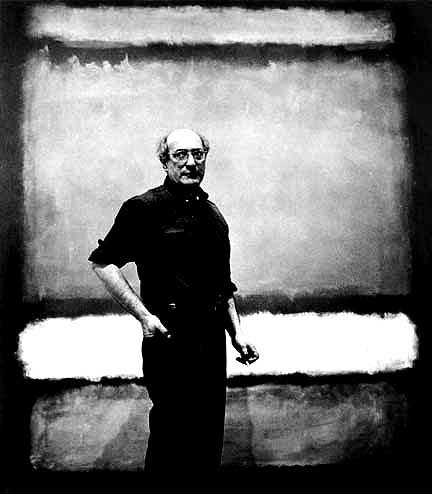

Given concerns with this tradition we approached Red by John Logan based on the New York School abstract painter, Mark Rothko (1903-1970). The London hit at the tiny and intense Donmar Warehouse has been imported to Broadway's larger Golden Theatre. The duo of Alfred Molina as Rothko and Eddie Redmayne as his young assistant Ken have recreated their roles.

As the subject for a drama Rothko is an intriguing choice. Unlike the artists listed above he was not known for flamboyant and dramatic actions. His soft focused, contemplative fields of color command enormous prices and are prized by collectors and museums. But the persona of Rothko would seem not to have marquee appeal. He is regarded as an artist of the first tier but never attracted the cult following of his peers Pollock or Willem DeKooning. Where they lived lives destined for pulp fiction Rothko appeared to live a life of intense introspection and subdued desperation.

Like several other Abstract Expressionists he smoked and drank himself to death. A suicide actually. Perhaps, as the Lee Seldes book The Rothko Conspiracy suggests, possibly even murder. At the end of his life he was in poor health with bad habits he refused to change. By then he was divorced and living in the studio. Under doctor's orders he was limited to easel sized paintings and works on paper. By any measure he had become a train wreck.

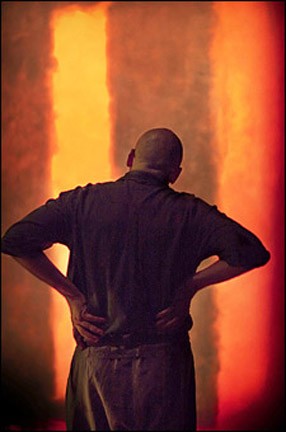

He was driven by a Nietzscheian vision of striving for epic achievements. Rothko was locked into a Talmudic struggle with the spiritual and Dionysian. Particularly in the late work he was a master of the dark side, the shimmering soft light of subdued contemplation. As he proclaims in this powerful and insightful play "The black is consuming the red." The dark was consuming the light.

Although he railed against the bourgeois he maintained the nine to five hours of a banker. As we see him in the studio, at work on a series of murals for the then under construction Seagram's Building, it was 90% about looking and deciding and just 10% of actually applying paint to canvas.

The architect and Museum of Modern Art curator, Philip Johnson, arranged for a commission. For the then handsome sum of $38,000 he was to create a series of individual canvases to be installed as murals in the upscale Four Seasons Restaurant. The building was the greatest work of its era by the Bauhaus master Ludwig Mies Van de Rohe. The building on New York's Park Avenue endures as one of the greatest accomplishments of 20th century architecture.

It was a great project but, for a restaurant. That was the problem. The scale and nature of the setting required an adaptation in the work. The space meant a change from horizontal to vertical format. For the first time he was involved with creating a suite of canvases meant to interact as an entire creation. Over three months, in 1958, he created 40 paintings enough for three full series to fill the space.

Since Rothko was inspired by Nietzsche's "The Birth of Tragedy" and viewed himself as a "mythmaker" he was surely an odd choice to "decorate" a restaurant. As he told John Fischer, the publisher of Harper's, he was creating "something that will ruin the appetite of every son-of-a-bitch who ever eats in that room. If the restaurant would refuse to put up my murals, that would be the ultimate compliment. But they won't. People can stand anything these days."

In what proves to be a climactic moment in the play Rothko called Johnson and announced that he would return the money and keep the paintings. They remained in storage until 1968 just two years before his death. Today, three groups from the Seagram series hang in London's Tate Modern, Japan's Kawamura Memorial Museum, and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

The aborted Seagram series led to another such commission. He was in poor health and the works were largely painted by assistants following his direction. They were dedicated in the Rothko Chapel adjacent to the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas on February 28, 1971 just about a year after his death

Between these great commissions Rothko created five paintings he donated to Harvard University in 1963. There was a triptych as well as two related canvases. They were given to Harvard University and not to its museum. It is interesting that he chose Harvard over Yale which he reviled and dropped out of. The decision was made to install them in the multi functional, pent house of the Holyoke Center. Rothko visited and liked the setting with its view of Cambridge although he was concerned with the light levels.

The materials he used for the Holyoke paintings, particularly Lithol Red, proved to be fugitive. The paintings faded dramatically and were also abused because of their public location. Because they did not belong to Harvard's Fogg Art Museum there was no curatorial oversight. Only when virtually ruined, in violation of the artist's gift, they were removed and placed in storage at the Fogg. In 1988, the paintings then damaged beyond hope of restoration, were shown at Harvard's Sackler Museum. The exhibition was accompanied by a scholarly catalogue, seminar, studies for the series, and conservation reports. The museum intends never again to display them although they are available to scholars. I reported on that project and exhibition for Art News Magazine.

Given all that art history it was fascinating and compelling to experience how John Logan transformed Rothko for the stage.

The drama occurs in the dark, grim, cave of a studio designed by Christopher Dram. The artist insisted on creating and viewing his work with low light levels. This atmosphere has been nicely achieved by Neil Austin. Against the walls of the studio are stacks of canvases that replicate the scale and design of the artist's Seagram series. Because of their reductive, minimalist simplicity they have been relatively easy to create for the purpose of this drama. This is always the slippery slope of dramas about artists. Julian Schnabel, a renowned artist, created all the paintings by Jean Michel Basquiat for the movie on the artist he created and directed. Ed Harris was remarkable channeling Pollock at work.

Before the play began we saw a rear view of Molina (Rothko) smoking and contemplating his work. Redmayne (Ken) a young artist enters. He is instructed rather harshly on duties and responsibilities as the artist's assistant. This is followed by if the terms are not acceptable "There's the door." Primarily Ken will be employed to help the artist stretch, prepare and prime canvases. To run errands and any other tasks required. There will be no teaching or mentoring involved. Rothko is emphatic that Ken is just an employee.

But, inadvertently, he takes an interest in Ken. Mostly as a receptor of his screeds on art theory and philosophy. He informs Ken that he and the other abstract expressionists, a term that does not really suit his style, had "crushed" cubism and surrealism. Their notion of the mural scaled, all over painting, and the integrity of the picture plane, as espoused by Clement Greenberg, had ended centuries of illusionistic space.

During that first day in the studio Rothko asks "Who's your favorite artist, don't think just answer." But the artist is less than pleased when Ken bursts out "Jackson Pollock." It's a logical answer. Rothko states that Pollock was a friend and good painter. Ken wants another shot at it. The second time he blurts out "Picasso." Typically, Rothko relates how he and his peers had destroyed Picasso, Matisse, and the School of Paris. Again, this is pure Greenberg whom Logan must have researched in some depth.

Mostly, Logan seems to get Rothko right. His grasp of the creative process and insights to the work are impressive. More significantly he has created a drama and not a documentary. Just how he formulated the artist's acerbic, misanthropic persona is questionable. From documentary sources how did he derive the compelling dialogue between the artist and the assistant he abuses?

Although Rothko worked for three months, in 1958, on the Seagram series, Logan has stretched this out to two years. He has the artist engaged in more looking than painting. Over this fictive arc to time we see how the relationship between the artist and his assistant evolves.

From the beginning Rothko has periodically asked Ken "What do you see?" During a moment when Rothko is contemplating a painting, asking rhetorically what it needs, Ken answers "red." The artist is enraged. How dare you? You know nothing about art and are just an employee.

But Ken holds his own. They start to scream at each other about all the aspects and possibilities of red. Red as in blood. The color of the blood that darkened when Ken's parents were murdered. It appears he was just a child. While Rothko is curious he is incapable of compassion.

At the end of this shouting match Ken assumes he is fired. To the contrary it is the first moment in which the artist comes to respect his assistant. "See you tomorrow" is his response while exiting.

The most compelling aspect of this work is how it captures the isolation and intensity of an artist's studio. Unlike a performing artist the painter works in isolation. There is no applause. Often artists like to work with ambient distractions, music, TV, books on tape. Here we see Rothko shuffling through a stack of classical LPs on a simple record player. This is mixed with original music by Adam Cork.

Alone in the studio Ken plays a jazz album while working on a stretcher. When Rothko enters he is angry. "What's that" he asks. "Chet Baker" Ken responds. It is a device that sets up Ken's growing strength and independence. As well as, the generational differences in their taste. The balance is tilting.

The dramatic high point occurs when they work together to prime a large canvas with an under coat of plum red. A bucket of paint has been mixed and cooked on an electric burner. This is poured into two containers. They work quickly with broad, wall paper brushes. The act is intense and furious. The audience is riveted to watch the paint slapped on. The color soaks into the unprimed, loosely stretched canvas. When finished they are both covered in red. Rothko washes it off at a sink but Ken remains painted. It is a surrogate for his pain and a signifier of his parent's murder.

There are exits and entrances signifying passage of time. Usually the artist changes from street clothes to work attire. In the final scene he enters dressed like a banker. He is over the top with anger. It appears that he and his wife have dined at the nearly finished Four Seasons. He is outraged by the noise and chatter of all those rich people. They will obviously pay no attention to his tragic paintings. Also, he has attended a gallery opening. While the gallery had formerly represented DeKooning and Motherwell, as well as his own work, now they were showing Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, and Warhol.

Again this is a stretch as these artists were not in the same gallery. Leo Castelli never showed the abstract expressionists. More likely this is meant to be Sidney Janis Gallery. It is true that collectors like Robert and Ethel Scull sold their abstract expressionist works, at a healthy profit, to buy cheaper pop art. They later sold the pop collection, at a huge markup, to settle their divorce. This goes on all the time. The conventional wisdom is buy low and sell high. Art is like any other commodity.

Ken argues for pop art as an expression of the zeitgeist. Of course, he was right. Hindsight is 20/ 20. But Rothko sees his work and that of his peers as a kind of high art. Ken reminds him of bragging about how he and his generation had "crushed cubism." And, that for all his ranting about the bourgeois, he is willing to take the money to "decorate" a restaurant.

In their heated debate Ken wins all the crucial points. He fights back saying that in the past two years of working together Rothko has no clue who he is. "You never invited me to dinner" Ken says. Why should I Rothko answers "You're an employee."

But, at least in this play, Ken has pushed the boss over the cliff. Rothko calls Philip Johnson and announces he is keeping the paintings. He turns to Ken and states "You're fired."

Ken demands to know why. There really is no answer. For a moment we believe that Rothko really does care for his assistant. He sees that he has grown and now has to strike out on his own. It is an act of mercy. Ken is ready to be more than an assistant.

In reality Rothko would need and depend on more assistants. It has become the norm for successful contemporary artists; starting with the abstract expressionists. The assistants largely created the Rothko Chapel series. There are ongoing debates about just how involved deKooning was in his late work when he was stricken with Alzheimer's disease.

While Red should not be approached as a documentary or literal biography it succeeds in providing compelling insights to the creative process. It is as close as most people will ever come to an artist's studio. Mostly importantly Alfred Molina and Eddie Redmayne have given astonishing performances. They richly deserved their standing ovation. We were privileged to experience 90 minutes of extraordinary theatre. Red is one of the best new plays of the Broadway season.