Katharina Grosse at Mass Moca

One Floor Up More Highly

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 15, 2011

Some 20 plus years ago Tom Krens, with an enormous ring of keys, walked me through the then abandoned campus of Sprague Electric in North Adams. The buildings we navigated were in varying states of disrepair. In some damage to the roof resulted in warped and buckled floors.

Back in his office, as director of the Williams College Museum of Art, he discussed a vision for what became, eleven years ago, under Joe Thompson, Mass MoCA.

During that initial walk through we paused in what is now known as Building Five. It was the largest of the buildings. Very long. About the length and width of two football fields. There were two floors flanked by enormous rows of windows. The natural light was intended to illuminate the factory space. Back then, as Lewis Hine photographs in North Adams have demonstrated, workers labored from dawn to dusk. Including children. There were horrific accidents before Labor Unions, remember them, brought in the 40 hour work week, safer working conditions, and under FDR and the Great Depression, unemployment benefits.

We have friends and neighbors whose families worked for Sprague and in the other mills including the one we live in. A lot of locals hope and pray that manufacturing will return to the region. There have been mixed feelings about the metamorphosis to an arts and tourism based economy.

A generation ago Krens had been inspired by visiting kunsthalles in Europe often housed in former industrial spaces. Now it just makes common sense that former factories get recycled as museums and artist live/ work spaces. Over in upstate New York a former Nabisco plant has been transformed into Dia Beacon to which Mass MoCA is most often compared.

The trend in the past decades of contemporary art has been toward the creation of enormous works and temporary, site specific installations. There has been an explosion of global biennials and a circuit of artists and curators thinking and working in terms of vast scale.

This is a quantum leap forward from when Jackson Pollock rolled out canvas on the floor of his East Hampton studio and danced around flinging paint from all sides. He invented what Clement Greenberg dubbed “all over painting” and predicted the “death of easel painting.” Clem was noted for hyperbole.

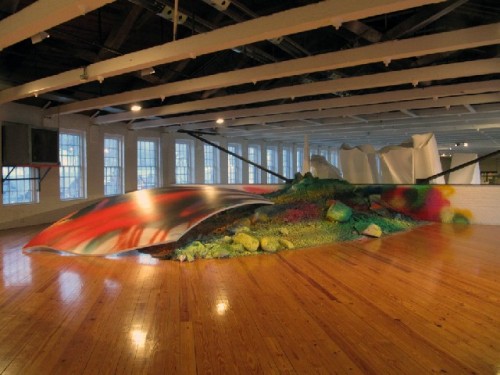

But there is a lot of post Pollock paradigm in Katharina Grosse’s large installation, "One Floor Up More Highly" which remains on view in Building Five of Mass MoCA through October, 2011.

Pollock revolutionized art by dripping and flinging paint using cans of commercial enamels and sticks. His hand and brush never touched the surface. To create this latest huge work the Berlin based artist and assistants have sprayed paint onto great piles of boulders and dirt. The color is splashed and sprayed somewhat randomly on walls, windows and floors. Stuck into the polychromed mounds, formed into several areas the length of the space, are beams of spiky Styrofoam, pristine white, evoking glacial ice formations.

Ambulating the vaulted space, with its flood of subdued winter light, the sensibility was that of an arctic landscape on acid with psychedelic colors. Tripping and grooving in a land of ice and high chroma snow.

Because Krens/Thompson removed the second floor we are able to look down into the space from the balcony that remains on one end. There is another less complex installation up there as well as a single, more conventional painting. Perhaps it is a sample of her gallery work. Below is a room that has floors and walls spray painted. There is a curious pile of old clothes on the floor, sprayed over.

At the pace of one per year by now a number of artists have had a crack at Building Five. It is one the largest indoor contemporary art galleries in North America. In addition to Dia Beacon there is also the pilgrimage destination of Marfa, Texas with Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation. Through Dia, the now deceased artist purchased an abandoned air force base. Chinati Foundation and the Donald Judd Foundation are now independent of Dia which oversees a number of site specific installations.

These developments of contemporary art have globalized the playing field. To get a true grasp artists and curators are constantly on the road. Decades ago, museum director, Kathy Halbreich, told me “We can no longer think about contemporary art in terms of nations. We must think in terms of continents.”

Which means that cutting edge contemporary art is beyond the grasp of most individuals. It is the mandate of Mass MoCA to exhibit a selection of what is being created on those continents. In the arts, as in sports, there are track records and batting averages. Curators do not always score home runs. Not every installation succeeds as it was intended. Big is not necessarily better. In the rush to blow up the scale what is often sacrificed is the intimacy and humanity of an artist’s vision. There is the daunting challenge to fill the space. It become rather like a fairy tale with the artist tasked to turn a room of straw into the visual equivalent of gold. Sometimes it results in, well, fool’s gold.

By collaborating with artists to create sprawling and complex installations curators have only plans and sketches to go on in their dialogues with artists. They have seen examples of other works but there is no way of predicting the outcome of a project. As working with Christoph Buchel demonstrated things can go terribly wrong. That mess left a huge dent in Mass MoCA from which it has now completely recovered. But it changed forever contractual relationships between artists and museums when creating installations and new works.

The series of installations in Building Five have resulted in mixed critical responses. They have ranged from spectacular to so so. Often the crucial difference is how the artists deal with that cavernous space. There is the option to fill it. The glass is half full. Or to leave it somewhat empty as was the case last year in an installation by Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. He created a Bauhaus like, upside down glass house. It commanded but a fraction of the space. Talking with him he described an aspect of the work entailed “the approach.” So the empty space was crucial to enhancing the large object within it.

There is a kind of yin and yang in the approaches of the minimalist Ovalle and the maximalist Grosse. Of course there is no right or wrong. Judgement is entirely in the eye of the beholder. De gustibus non est disputandum.

It is the task of critics to make those aesthetic decisions. Like artists and curators we also have our stats and batting averages. Rather than make judgments it is more productive to engage in dialogues with the work. There are times when works in question are right and wrong. Yes, there are occasions when we love or hate aesthetic experiences. It is compelling to sound off when art is so clearly hot or cold.

Most often, however, contemporary art confronts us with mixed and gray reactions. One litmus is the holding power and lingering after images of an experience. What is the half life of a work of art? How long does it stay with us?

What is the difference between the immediate impact of an installation? And how it remains with us in memory. The Grosse installation surely has high impact. It was an assault to the senses. But like much art of spectacle it is more about unique special effects than compelling ideas. Yes it was interesting and outrageous to see those polychromed mounds of dirt and boulders and shards of Styrofoam. But do we dare to ask what do they mean and add up to? Is it like too many action films with spectacular visuals and stunts but not much of a plot? So is this work by Grosse flash art or just a flash in the pan.

Only time will tell. Mostly, in contemporary art, it is a luxury we cannot afford.