Nasreen Mohamedi at Met Breuer

Work of Exquisite Indian Artist Launches Rebranded Museum

By: Susan Schwalb - Mar 15, 2016

Nasreen Mohamedi

The Met Breuer, NYC

March 18-June 5, 2016

The new Met Breuer on Madison Avenue opens to the public with two inaugural exhibitions, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, a thematic survey featuring unfinished art from the Renaissance to the present, and a retrospective of the Indian modernist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990).

It was nice to be in the old Whitney Museum building again although only superficial changes and repairs such as cleaning walls, floors, or removing chewing gum were made in an attempt to restore it to its original state. The new restaurant won’t open to the public until the summer.

I briefly saw the Unfinished exhibit, but visited the Mohamedi show several times, and particularly enjoyed a walk through the exhibit with one of the curators from India, Roobina Karode, Director and Chief Curator of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi.

The work came to my attention in 2008 through her second American solo show at Talwar Gallery in NYC entitled the grid unplugged. Immediately there was a strong kinship with the artist’s ink and pencil drawings involving hundreds of precise lines. Since then her work has been more familiar through reproduction. I even made a few drawings in homage to her work. This process revealed how complex her drawings were with their unique and individual style.

The current exhibition includes over 130 paintings, photographs and drawings which survey the different stages of her career. A catalogue accompanies the show with several essays and reproductions of most of the exhibition.

Nasreen Mohamedi was born in Karachi (British India, now Pakistan) and then the family moved to Bombay (now known as Mumbai). She studied at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London (1954-57) and then at a private atelier in Paris (1961-63). After returning to India she traveled the country extensively along with trips to Iran and Turkey. In 1972 she moved to Baroda in the western part of India to join the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, one of the leading art schools, where she stayed until the end of her life. After an early failed engagement she never married, and even when she was ill, lived alone, much to the consternation of her family.

According to Roobina Karode who studied with Mohamedi (and remained a close friend throughout her life), she was an extremely private person and never talked about her work. She never titled or dated anything, preferring not to impose her ideas on the viewer. Her studio was a bare-bones space with beautiful light. She practically worked on the floor, using an architectural drafting table while sitting in a classic cross-legged yoga position on a small stool barely a foot high. Hindustani classical music played in the background and she was oblivious to what was happening around her.

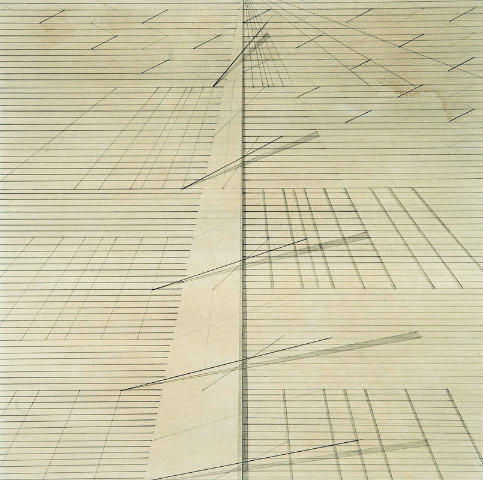

The exhibition is roughly divided into three sections by decade. In her early work in the 1960s she experimented with line and washes in her prints, drawings and paintings. She was influenced by abstraction that was taking over America and Europe. She became friends with V. S. Gaitonde and they rebelled against the prevailing popular figurative style of the times. Gradually she gave up painting to focus only on drawings. By 1969-1970 premonitions of her coming physical limitations (she had a rare neurological disease similar to Parkinson’s, which also afflicted two of her brothers) obliged her to turn to drafting tools to make the perfect lines she desired. Often she worked on graph paper or used very light pencil grids as her guidelines.

A first glance at drawings made of hundreds of lines may create an illusion of regularity, but close study reveals an extraordinary complexity in each image. I believe that the artist occasionally used tape to create the many different shapes and forms. She worked with a fine rapidograph pen as well as a ruling pen, often watering down the inks to obtain light grey lines (sometimes used as guidelines).

I am still overwhelmed by control over her tools, in spite of unsteady hands. As one who has used those kinds of pens I know how easy it is to make unintentional spots but there are none on these drawings. It is said that she had a special swirl at the end of each line and when it failed she just threw the drawing away. At one point she began to focus on a square format creating what can be loosely described as landscape-like linear forms where numerous lines cover the surface and the drawing sometimes has a sense of a horizon line. The final works in the 1980s gradually became lighter and more open with trapezoid forms and arcs that float in the center of a rectangular page. Mohamedi was very interested in the work of Kandinsky and Malevich and one might describe her work as a cross between constructivism and minimalism.

The exhibit contains numerous photographs that the artist took during her life, although they were never meant to be exhibited and the artist never showed them. They can be viewed as sketches or ideas for some of the drawings. Most of the photos were only printed in 2003 as editions, probably as a way to expand her limited oeuvre. I am not sure that Mohamedi would have wanted us to see the subtle relationships between her line drawings and the back and white photos that she may have used like a sketch book to document ideas. Mohamedi however did keep very extensive private diaries, mostly in English, and some of them are included in the exhibition. They reminded me of the “list drawings“ of the sculptor, Nancy Grossman, where some text is blocked out and small shapes and designs mix with finely printed letters.

Mohamedi is considered one of the first two abstract women artists of India, the other being Zarina Hashmi who spent most of her life in New York City. Mohamedi did travel a little in the US and knew the work of Agnes Martin but probably only by reproduction.

This exhibition invites us into a personal and private world made up of lines that transcend any obvious narrative or subject matter. It must be seen to be experienced and you are encouraged to make a pilgrimage to the Met Breuer. Be sure to give yourself the time needed to experience this amazing work.