Sculptor Len Poliandro

Working with Metal and Glass

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 16, 2015

Charles Giuliano I was introduced to your work in Williamstown. Now we are sitting on the terrace of your home in Tuscon, Arizona looking at works created in the past few months. I sense a change and can we talk about that.

Len Poliandro There has been a change which I have experienced internally which has to do with movement. Previously I poured glass vertically on top of metal sculpture to give a feeling of the yin and the yang of glass and metal. Now I hold up the piece to allow gravity to give it more of a horizontal look. The metal bases also have more of a movement coming from the bottom and swirling as you can see in the two Dancer pieces. So that has been the change and I feel really good about it. It's a different style and we are all connected through movement.

CG This morning when we were talking you mentioned three elements that are important in your life starting with freedom. This came out of experiences in your family. The result was that freedom led to adventure. Which in turn led to beauty. Can you talk about how these principles have resulted in your voyage?

LP As it is for all artists the work comes from the internal. The life you live and what you are experiencing. Most of this comes from the unconscious. So I have asked myself what kind of a life have I lived? What kind of a person am I? Then you think OK I'll write an essay on that. I challenged myself to do it in simple words. This has been going on for some time and I came to those three words: Freedom, adventure and beauty.

We're told that we have free will but we don't always exercise that freedom. Coming from a controlling Sicilian background I realized that when I was free I was playing. As I was playing I could go to the boundary and have an adventure. Some people stop there but what I found was that adventure gave beauty to my life. The beauty is what I am being taught. The beauty of nature. The beauty of the universe and the stars. Which I am studying.

Living in Arizona I am more into nature. We are surrounded by the dramatic desert landscape. I'm saying this hoping that you will come up with your three words. My three are not your three or perhaps they are in different sequence. This really tells me who I am.

CG When we first met during a social occasion in the Berkshires we discovered the commonality of having tough, authoritarian, Sicilian fathers. There was an immediate bonding through that. This morning I asked about your father and what he did. You described Sal as working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard during WWII as a welder. He developed the skills to become a master welder. You described that if there was a broken gas main he was the guy who got the call in the middle of the night for a very dangerous job. It conveyed to me that even though there was a lot of conflict you respected him as an accomplished craftsman.

Looking at the wall at the edge of the terrace with a display of your welded sculptures there seemed to be an intuitive connection to your father as you were telling me about him. There seems to be a paradox of breaking away from him and yet the lure of that heritage now manifest in the form and technique of your creative work.

You described taking a welding class at a high school during your first years in the Berkshires. You discovered an affinity for working with metal. But you made the point that your father was not a mentor. You described the influence of a blacksmith. The process of making art started when you were about 54. Previously you and Ling had studied architecture as Taliesen Fellows for a year. There had been a prior involvement with the arts.

Your business was in the orient so you traveled extensively and experienced the culture. It seems that starting to work with metal evoked a cathartic experience.

LP I can't thank you enough because you have encapsulated this for me so beautifully. I would never be able to put it together as you just did. So, Charles, thank you. That's step one. I began in the arts when I was 54 but my business was in textile design and converting. I was an entrepreneur delivering a product of quality. I never saw myself from an art point of view.

CG But there were many aesthetic decisions involved in the choices of colors and fabrics.

LP The quality and techniques. How many screens and colors. So you had to know that kind of movement on printing. If I came up with an idea and sold it then it was their product. They made the garments which were sold to Saks Fifth Avenue. So it wasn't an arty piece that I was going to take to my living room. I see an artist as more than a craftsman. A craftsman may have a certain technique but he doesn't take it to the next stage. Art for me has a message.

While we were in Taliesen we had to do a project. Everybody has to make a piece. Of course I was terrified because I had never done that. You might do a drafted drawing on an idea that you had. Not an assignment but an idea. I made a piece that represented a roof top. When I was in Australia in Sydney and saw the opera house that roof blew my mind. It was the only plane I ever missed in my life because I walked around that Sydney Center for hours.

I didn't know it at the time but that roof represented for me a sculpture. So I decided to make a roof. My roof. I made this piece and it became a lamp. I wired it and wrapped a cloth around it. There were about thirty of us that year and we all presented our piece. When it came to be my turn I set it up and took the cloth off so we could see the lamp and it was quite nice. We worked on it for about a month and I was amazed at the reaction.

I had crossed over to a new place that was cathartic and terrifying. I still have that piece in Williamstown and look at it every now and then. That was that was the beginning.

We finished with Taliesen and retired. I felt the urge to make something so I took a course in welding at a trade school. I studied for three months and loved it.

CG Did you get the sense of coming to understand something about your father?

LP Absolutely. His touch. The sparks in your face. They burn your hair so you have to wear a hat. How hard yet what a beautiful art it was. He didn't do art he was just a great craftsman. He never got to that stage.

CG David Smith was a pacifist so to avoid the draft he welded tanks in a factory. He created a series of bronze reliefs the "Medals of Dishonor." What he learned commercially during the war he applied to later making sculpture from industrial materials.

After we met you invited me to lunch after which we visited your studio. I asked if you had shown the work and you said no. I told you that once you make it the work doesn't belong to you anymore. It belongs to the world and has to be seen.

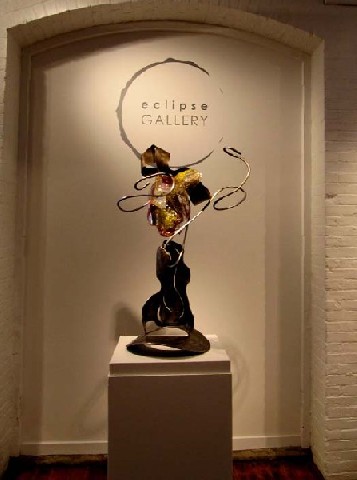

I encouraged you to put a piece into a show I was organizing for the Eclipse Gallery in North Adams. So you exhibited a piece in the Berkshire Salon. Later you had a two person show there with the abstract painter Dawn Nelson. The show was well received and a friend of yours made a video work based on it. It was interesting to me that prior to that the idea of showing the work had never occurred to you.

LP For me it was the freedom to have the adventure of making the work. At first that was enough for me. Then the way you presented it I realized that you were right and I had to show the sculptures. The beauty in the work then speaks to me and I know exactly where that came from. To show it? Why? I never got to that level of sophistication. So your invitation was wonderful. It was a bit terrifying because I was putting myself out there. But I had a feeling that when I come to a boundary I'm on the right track. From comments I realized that people were relating to the work.

When the show came up with Dawn I had 18 or 19 pieces on view and it was fabulous.

CG Other than Taliesen you are a self taught artist through trial and error. You haven't gone through the dialectical process of training. When I first encountered the work it was not very evolved. But I sensed a passion and the challenge of combining metal with molten glass. That represented a daunting experimental process. There was a great sense of potential for the work which has now developed in such a meaningful way encountering this new body of work created in Arizona.

The growth and synergy of glass and metal is palpable. Also the metal has evolved beyond being an armature for the glass and even exists without being enhanced in that manner. So the advancement of form and sculptural presence is formidable.

LP I spent a lot of time in Asia. Hong Kong as my home base. I got introduced to the concept of opposite the yin and the yang. One is not better than the other. Night is not better than day and day is not better than night. Both are needed and always there. It's the concept of picking x and not being afraid of y. When I started to make work that concept kept coming to me and how could I show that? By then I was into a couple of years of using metal and forging techniques. Glass just came to me. It's brittle and transmits light. It holds color. It's the perfect complement I feel.

When I came up with that everyone told me you can't do it because of the coefficients of how glass and metal cool. One cools faster than the other and they'll pull apart. I took a workshop with Jean Koss from New Orleans. He's the director of a glass studio. When I explained what I wanted to do he said "You know that doesn't work." But he didn't say "It can't be done." He said "Let's try it." He said let's do it slowly and used the annealer. So he was on the track of bringing the temperature down slowly and it came out. It didn't break. Then he said "Ok, now make a hundred of them. Then you'll really know how to do this."

Of course when I started on my own I was breaking nine out of ten. But after a couple of years I learned how slowly you have to bring down the temperature.

CG When you were breaking so many at what point did you become discouraged?

LP Never. I read about Edison when he was trying to find a filament for the light bulb. He did over 4,000 experiments. He would say "I'm half way there." So I would say to myself "I'm half way there." That first piece was like a space trip. I still have that piece. Because he said "Let's try." Why aren't all teachers like that? Don't endow me with your doubts. That was the key and launch of this body of work.

CG Tell me about working in Brooklyn.

LP I heard of UrbanGlass which is one of the most renowned studios in the east. There were ten of us taking a class at Urban. It lasted for several days. When it was over I contacted four of the guys who had taken the class. We decided to continue together. To do this work you need a team. One guy opens the furnace while another had the ladle. Another gets the color and picks it up. You can't do all this by yourself. It's team work and connectedness. There are no words. You're dancing, moving. You're helping and protecting each other. You're playing with 2,000 degrees. You have to watch your butt. It's a complex process. We worked together for ten years and all took turns. In just two minutes you have to put your piece away in the annealer. You have to work very quickly.

CG How long were the sessions?

LP We would meet on Saturday and bring down the pieces we wanted to do. They were working with metal and glass in different ways. Some were using just the form pouring glass into it. Some were using the glass with metal tongs to form it. We were all doing casting which means that you go into the furnace with a ladle like a giant soup spoon. You scoop it up and put it on a marver which is a heavy metal table. Then you can start doing what you want to do.

CG Do you use torches.

LP Yes, at the end. That's called neutralizing. The glass comes out at 2,200 degrees. Then you put your color on and mix it real quick. In my case scoop it up and lay it over the sculpture form. Then torch the whole thing so hopefully the glass and the metal are the same thing. That's all within two minutes. Then open the annealer and what's called "put it away." There's no tweaking it's totally intuitive. When it comes out of the annealer there is no way that it can be duplicated. It's unique and a product of that moment.

CG Where does the growth come from over the years?

LP There is the accumulation of experience. Also the attitude is the growth. Now my mind is represented by the words "layers of light." When we see light we think it's all one piece. I'm seeing light right now coming from the sun which is 93 million miles away. That's true. But when I see light from the stars some of then are 93,000 light years away and are sending their light. Some stars are only 500 light years away and sending their light. So light is coming to me from different time points of view. But I'm seeing it now. I know that's not happening because it's coming from different viewpoints.

The growth comes from how can I exercise that concept in a piece. I don't try to use my mind to figure it out. I just get into the studio and begin to play.

CG When you go into that two minute dance with the glass what is different now from what it was then?

LP You always have an experience within a range of things that have happened. The beauty of that two minute experience is that you're reacting to what you see. Sometimes the glass is going to the left. You don't have to try to make it go to the right. Maneuver it on the left. Hey, maybe I ought to turn it upside down. You're dealing with the situation as it comes.

CG Have you tried other techniques like blowing or casting?

LP Yes. I'm putting it into molds and taking it out. I'm not doing blowing. That's another 20 years.

CG Having relocated from the Berkshires and commuting to the studio in Brooklyn how have you continued the work now in Arizona?

LP Coming here I didn't have a clue. I didn't come with a list of these are the things I've got to have. I came with total freedom to work with what I find. Lucky for me just 30 minutes away is a place called Sonaron Glass School. It's a great facility with terrific people. It's not as big or sophisticated as UrbanGlass but it has everything I need. I have two teachers who I hire for the sessions. I'm buying the glass and annealer space. I go in with the metal pieces and the three of us do the job. We work nicely together and they are very qualified.

CG Early on one in ten pieces broke. What's the success rate now?

LP With pieces I'm pouring into molds and taking out there has been some breakage. With pieces that are strictly sculptural on the metal the success is almost 100%. An occasional piece will break or have a crack. Even though you have annealed it correctly there will be a little crack. A flaw. Some people get very upset and throw it off the cliff. I think that's an insult. I get what I get and say thank you. Sometimes if the glass is going over metal that's too sharp or pointed it will get what they call a check. I could care less. To me it's perfect the way it is. If it's severely cracked I'll break the glass and use the metal again.

CG Are you planning to show this new work?

LP Tuscon is a very sophisticated place. At University of Arizona there are highly qualified people from around the world teaching, studying. This is not a backward area forty minutes from the Mexican border. There's a lot of subtlety and I want to expose myself on that level. There's a few shows that I've qualified for. One coming up this weekend is the Luna Planetarium Show which comes up once a year. It's run by the people in the astronomy department. It was juried and I was selected. When the Gem Show comes that's the big, big show here. They have a sculpture show and I've been approved. It's in a giant warehouse in the middle of the Gem Show. Last year I went to check it out and the quality of the work was astonishing.

CG It's stunning to see your work in the context of the distant mountains. They go together so beautifully.

LP The surroundings, the view and the sunlight are all a part of the work. The best gallery in the world is right here.