William H. Holst’s Provincetown: Point of Origin and Homecoming

An American Modernist Painter and Educator

By: Andrew W. Young - Mar 17, 2025

A disciple, William Holst (1912-1995), carried Hans Hofmann’s teachings with him as an artist and educator for nearly a half a century. Hofmann’s ideas swept Holst to his true north. A modernist pilgrim, Holst spread his own version of Hofmann’s philosophy from Provincetown throughout the northeast. Holst developed what some refer to as Holstian Theories which included an expansive exploration of Hofmann’s ideas, but largely carried out in black and white.

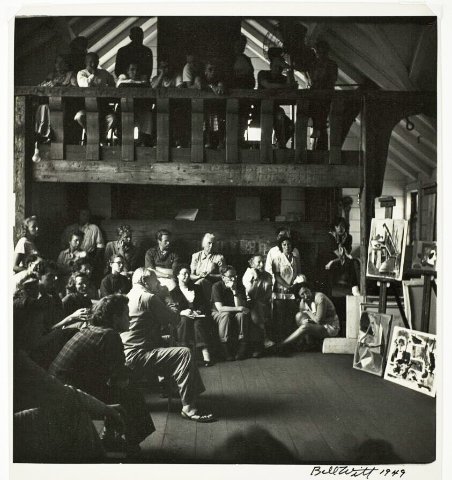

By the time Holst arrived at The Hans Hofmann School during the summer of 1949, he was the chairman of the art department at Colby Sawyer College and a nationally exhibited and award-winning artist. Like many 1st generation Abstract Expressionists there, he came of age in the Depression and was a WWII Veteran.

.It was a heady time in Provincetown during the summer of Forum ’49. The concurrent Gallery 200 show included “works of America’s foremost abstract painters” at 200 Commercial Street. Forum '49 “was a gathering of artists who were soon to be legends’” according to “P-town, Art, Sex, and Money on The Outer Cape” by Peter Manso.. The exhibition of 50 Cape artists included work by Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Adolph Gottlieb, Perle Fine, Mark Rothko and others. It was "the first New England exhibition entirely devoted to abstract painting" according to art historian Jennifer Liese.

Wolf Kahn, said the Hofmann School was the place to be at that time.

Haynes Ownsby recalled it was like the biggest classroom in the world, the whole of The Museum of Modern Art were there.

Holst’s classmates the first summer of 1949 included Elaine de Kooning, Nelle Blaine, Larry Rivers, (according to "9th Street Women") John Grillo, Fred Mitchell, Michael Lowe ("Color Creates Light"), Joan Mitchell, Myron Stout and Dede Maeght (Hofmann papers, Smithsonian). Other notable artists were classmates of Holst during the ensuing summers.

Hofmann believed abstraction begins in nature. In Provincetown, nature abounds as does the sea, its tides and their movement and depth (fathoming, sounding, incoming, outgoing). Holst’s non-objective work is as organic as it is elemental.

For Holst, these years were a most welcome and quite remarkable modernist baptism, and it took hold of him. Formal Non-Objective Modernism was less a pilgrimage than an inner compass, core to his existence. For forty five years he embraced and imparted Hofmann’s theories of spatial dynamics and push/pull.

The summer following Holst’s last with Hofmann, The Provincetown Art Association's first 1955 exhibition, featured Holst's "Suspended." The show included a who's who of Provincetown painters: Forsberg, Hofmann, Hawthorne, L’Engle, Botkin, Lazzell, Yamamoto, Marantz, Freed, Orlowsky, Hensche, Moy, Davidson, Kaplan, Hondius, Feinstein, Maril, Moffet, Wilson and others. What a thrill it must have been to exhibit alongside his mentor.

Friendships forged in these years endured. Holst made “Provincetown jaunts” well into the 1960s. During Holst’s tenure at Colby Sawyer College, his art department hosted guest lecturers and mounted exhibits on contemporaries with Provincetown connections including: Elaine de Kooning, Geoge McNeil, George Segal, Allan Kaprow, Sam Feinstein, Lester Johnson, and Paul Burlin among others. No doubt, Holst’s Provincetown years fostered the relationships underpinning all this.

Christine Gardner prefaced an interview with Holst for the February, 1984 issue of Art New England Magazine: "In the Provincetown of the ‘50s a group of young painters gathered around Hofmann, attracted by his insistence on depth, simplicity, and the ‘emotion-releasing faculty of color.’ William Holst was among them."

(Art New England, " On Painting: A Dialogue between William Host and Arthur Yanoff" by Christine Gardner, February 31, 1984.)

While Holst’s mature work is grounded in structure and place it is abstracted to association and articulation. Therein lies a modernist tenet: a painting being something not of something.

Holst’s artist’s statement for his 1977 retrospective posits: “Art brings an expansion of perception to take on new meanings experience. Objects and forms and identities and the invisible becomes visible…felt tensions, expansions and contractions of space are stated in pictorial equivalents.” His artist statement for “The Elusive Object” (1986) echoes Hofmann again and concludes “the mastery of the medium…brings the flat surface into a three-dimensional reality and experience - commonly called plasticity.”

The essay for his 1977 retrospective reiterates "Study with Hans Hofmann in the late forties and early fifties played a most important part in my development as a painter.”

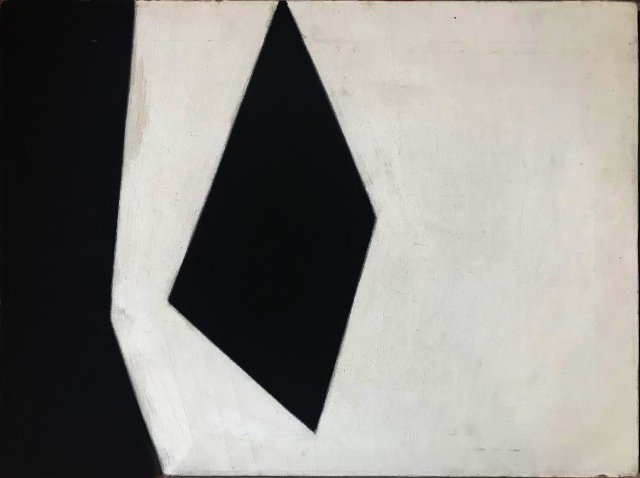

In his characteristic use of only black and white Holst used “the barest means of creating form.” He quoted Hofmann “it is more important to make the most of the least… not the least of the most.” The argument advanced “Mr. Holst is more concerned with the relationships existing between objects than the objects themselves.” In stripping away layers, he got to the heart of a thing - went deeper.

Richard Schiff observed Seurat sought to “fathom the surface.” “Fathoming” articulates Holst’s expression in black and white of Hofmann’s theories about planes, form, space, advancing and receding forces (i.e. push and pull). Holst took Hofmann’s theories to a different level in black and white.

Fathoming: the double entendre is exquisite. Holst’s paintings are cerebral and the “modulation of space” and depth evokes the seafaring character of the Outer Cape.

There is also a duality to Holst’s legacy. Hofmann said Holst showed “promise of turning into a quite remarkable cultural asset for this country.” He did, yet his legacy is, well, shallow. As Alana VanDerwerker observes, he has largely slipped through the cracks of art history.

Although he:

- was in Carnegie Institute’s 1941 “Directions in American Paintings?.”;

- won The Currier Museum of Art Award in 1971;

- is represented in the collections of the National Gallery, The Addison Gallery of American Art, The Provincetown Art Association and Museum, The Cape Cod Museum of Art and other esteemed institutions;

- was included in the Portland Museum 2019 show “In the Vanguard;”

- can be found in Hofmann’s “little black book;” and

- was included in the Provincetown Art Association and Museum’s “Remembering Forum ’49" during the summer of 2024, again alongside Hofmann - some spackling in the cracks of art history; he is known to very few as the successful, principled, and faithful modernist painter and teacher he was. Those who knew him are devoted to his artistry and teaching.

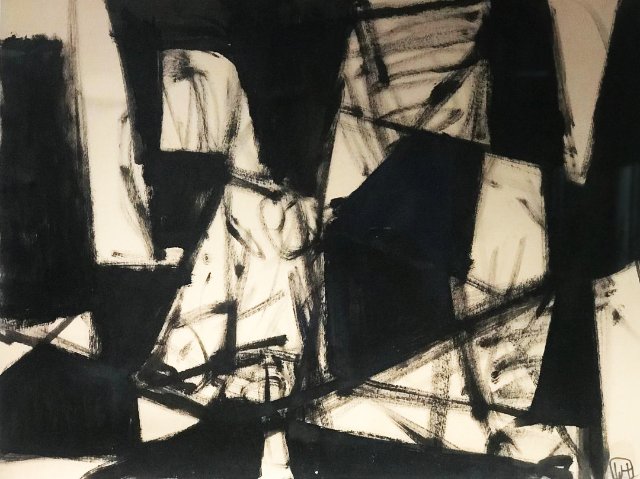

Carol Lummus, artist and former Holst student, celebrates “the essence of all Hofmann’s theories in William Holst’s black and whites…reduced and simplified.” With masterful measures of expression and restraint, Holst achieves a sophisticated balance. “VII•14•83” is elegant yet raw and refined yet primal: dignity in the face of turmoil. He was reserved, and even shy, but rigorous and uncompromising in painting and teaching.

In March, 1962, James Beck of “ArtNews” saw Holst at “a point of decision in black and white oils. Some … ‘purist’ in execution... the bulk are more loosely handled.... the most successful .... has a kind of logical irrationality.” To me, that sounds like math in the music or sextant in the storm. “Logical irrationality” is a verbal incarnation of Holst’s energy, tension, and ultimate balance in push and pull – where he achieved grace.

A 1974 Colby Sawyer press release reports Holst’s style evolved over twelve years. No doubt, but at least as remarkable is how unflinching his effort, results, and devotion to Hofmann were. The same twelve year gulf between, are unwavering. Anne Neely admired the “sheer rightness” in his conviction. Arthur Yanoff expounds “as a painter, Bill had great integrity. He believed that experienced form had to be fought for, no easy shortcuts.”

Holst’s legacy as a teacher is rich. More than a few noted artists point to his influence as foundational. The ripples were recently noted in an exhibition essay by Emily Mckibbon for a 2024 show of noted Canadian artist, Ron Shuebrook. She wrote “Shuebrook was mentored by William Holst, Myron Stout, and Fritz Bultman, all former students of Hans Hofmann, who inherited and shared Hofmann’s deep understanding of … modernism.”

So, along the lines of charting a course, embarking and disembarking, isn’t it poetic Holst’s lithograph, “Fruit,” printed by Maeght in Paris in 1967 was included in “Remembering Forum ‘49” in Provincetown, crucible of Holst’s modernism, seventy five years after where he was set on his modernist course. There his work was, hanging among giants, with his classmate John Grillo and his beloved teacher, Hans Hofmann – a homecoming.

Images and references not otherwise noted are courtesy of williamholst.info.

For more information about, to share information on, or inquiries regarding William Holst

The William Holst Project

Website: williamholst.info

Instagram: @williamholstinfo

email: thewilliamholstproject@gmail.com