The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist

19 Years: The Art of Mystery and The Mystery of Art

By: Mark Favermann - Mar 18, 2009

In "The Final Problem" by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Mona Lisa is stolen from The Louvre and the French government thoughtfully called in Sherlock Holmes. Holmes is successful in its recovery, but soon afterwards on a holiday in Switzerland, he encounters his arch nemesis. Thus, the final battle between Professor Moriarity (the Napoleon of Crime) and Holmes which culminates at the precipice over Reichenbach Falls where both Moriarity and Holmes, wrestling between good and evil, appear to fall to their ultimate deaths.

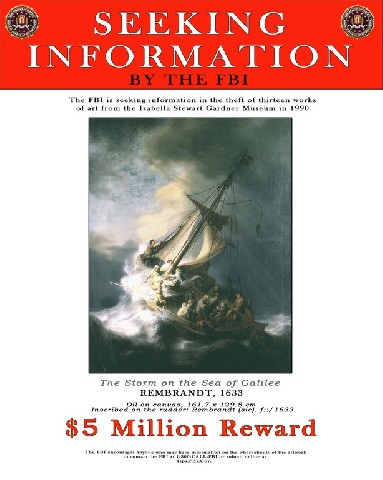

This mystery is similar to the nearly two decades of verbal and intellectual wrestling over the whereabouts of the art stolen by unknown thieves from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum on the night of Saint Patrick's Day, March 18, 1990. The problem is that there has been no Sherlock Holmes figure and no recovery of the stolen art treasures. Viable leads and clues have fallen to their deaths. After much journalistic research and police detective work, along with an offer of $5 million dollars by the museum and its insurance companies, we seem to know little more than we knew almost two decades ago.

What we do know is rolled out almost every year at the heist's anniversary by local and national newspapers and magazines enjoying a bit of tabloid journalism. Now there are 21st Century blogs. Vague leads, discussions about potential (mostly deceased or imprisoned) thieves and recovery dead ends are coupled with acknowledgement of colorful local, usually low level, hoodlums, ex-cons, notorious art dealers, and even IRA terrorists with little or no connection to similar crimes. Theories have been presented yearly like a journalistic pilgrimage to an art theft Mecca.

There was wholesale bungling at the start of the aftermath of the case. The FBI insisted on investigating alone. There was no formal assistance requested from the Boston Police or the Massachusetts State Police by the less than erstwhile FBI. The agent in charge of the initial investigation was all of 26 years old. This suggested the lack of seriousness of the effort by the G-Men. Certainly, master Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot, would have used his grey cells to confer with whomever he could have. Mrs. Marple would have seen some parallel to experiences in her home village of St. Mary Mead. Wet behind the ears FBI agents did not even know what they didn't know. It seems that the FBI just did not take the Gardner Museum robbery thoughtfully or seriously enough in the beginning.

Even today, the various "serious" writers of books and articles cannot agree on who the thieves were or might have been. The police probably have another group of suspects or individuals of interest as well. The master criminal on the lam Whitey Bulger's notorious name is always thrown into the mix of probable villains. But, it is doubtful that he was a great art lover, or had the patience and knowledge to fence rare pieces of art. It just was not his modus operandi. But, who knows? Perhaps, the art is sitting securely in a barn in the west of Ireland. Hopefully, the barn is climate controlled and has sensitive low light. The question here is why would this help Whitey?

In 1974, an IRA group robbed Russborough House, a private grand estate outside Dublin. The gang took 19 paintings including a Vermeer, a Goya, and two Gainsboroughs. The art was pried from their frames by screwdrivers. The gang tried to trade the art for imprisoned IRA members. No deal was made. However, all of the art was recovered less than two days later.

Another suspect was antiques dealer and Scotland Yard informant, a character who rejoices in the name of Michael van Rijn. He was living in NYC at the time of the Gardner heist. Though denying any involvement in the case, he claimed, in a 2001 Atlantic Monthly article, that he had information about who had done it and a possible location of the stolen art. Shortly after the article appeared, he refused to say any more and went into hiding in England claiming fear for his life.

Myles Connor was a notoriously affable thief and rock musician in the Boston area. The son of a cop, and the brother of a priest, he attended art galleries and museum exhibition openings and actually seemed to like and be knowledgeable about art. Connor was serving 15 years in a Rhode Island prison for stolen antiques when the Gardner Heist occurred. He surfaced early on as a possible mastermind of the theft. He gave several interviews to the Feds with no real results.

Connor claimed in a 1997 Time interview that if he had planned the job, he would have taken Titian's 1562 "The Rape of Europa." This magnificent painting is considered by many art historians as the greatest painting in any New England museum collection. The Gardner robbers left that painting on the third floor untouched. Conner also claimed that in the 1970s, on a visit to the Gardner, he discussed how easy it was to steal artwork from the Gardner with a criminal associate Bobby Donati. Supposedly, Donati showed great interest in a Napoleonic flag finial. This was one of the least valuable Gardner pieces eventually stolen.

Soon after Conner's Donati meeting, a Rembrandt was stolen from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Never admitting the theft, Conner arranged its return by avoiding prison time for another art theft in Maine. But, Conner claimed that Donati and his crony David Houghton arranged the Gardner Heist on their own based upon Conner's earlier plan. Instead of using art thieves, they used less sensitive armored car robbers. Donati was found in 1991 dead in the trunk of a car hogtied and stabbed. Houghton died in 1992. Conner suggested that the two told him where the loot could be found, but would have to be let out of prison to secure it. The Feds did not play along, but they did raise the reward to $5 million dollars from one million.

Another person of interest was William Youngworth, a career criminal, thief and conman. He was also an associate of Myles Conner. In 1997, Youngworth contacted Boston Herald reporter Tom Mashberg and claimed that he had the art. Mashberg went on a blindfolded trip to an unknown location with Youngworth. There he was shown what looked liked a rolled up canvas containing Rembrandt's "Storm on the Sea of Galilee." Mashberg was allowed to take some paint chips for analysis. Youngworth wanted to return the art in exchange for immunity for Connor and himself, release of Connor from jail, as well as the $5 million reward.

The FBI wanted to get one of the 13 art objects as a show of faith. Youngworth gave them nothing. The paint chips were analyzed and after a bit of controversy were announced as fake. Youngworth was sent to prison for a separate stolen car felony. Both Connor and Youngworth were released from jail in 2000. Various investigators felt that amnesty would lead to the pair recovering the art. But others say that Connor had offered many contradictory theories that just did not add up.

Another strange story is the aborted attempt in the mid-1980s to rob the Hyde Museum at Glens Falls, New York. The Hyde Museum includes an amazing, world class collection with superior Rembrandt and Ruebens paintings. It is housed in a similar building to the Gardner, also a Renaissance Florentine palazzo. It is a similar private collection turned into a museum. Many of the Hyde family artworks were acquired for them by Bernard Berenson. He was the same noted Renaissance art expert that Mrs. Gardner used to purchase much of her collection. Was the attempted robbery at The Hyde practice for the Gardner Heist?

What happened to the works of art is even more of a conundrum. The barn in the west of Ireland is one location. The untouchable underground vaults of secretive underworld connected James Bond-like wealthy arch foes like Goldfinger or Bloefield are other locations. Of course, there are the thoughts of rogue Arab oil sheiks sitting in their elegant and opulent desert palaces with smiles on their faces privately looking at the Rembrandt and Vermeer paintings. In the early 1990s, thoughts of sinister Japanese Yakuza chiefs owning the art were prevalent, but when the Japanese Yen fell, and the whole country went into stagflation, less focus remained on Japan connections to the affair. Practical Japanese would have traded the pieces for gold or pearls. The major artworks from the cache were and still are too hot to handle.

Boston had another great robbery in the 1950s: The Brinks Robbery in Boston's North End. The holdup was at a building now used as a garage on Commercial Street the extension of Causeway Street near the Boston TD North Garden. This January 17, 1950 heist was considered the Crime of the Century for many decades. The mostly low level hoods involved in the caper all kept their mouths shut and supposedly did not touch the loot.

The statute of limitations was about to run out in 1956 when one of the gang, Joseph "Specs" O'Keefe named names after being nearly killed by a hitman, Elmer "Trigger" Burke, sent by another member of the gang, Anthony "Fats" Pino. Pino was the brains behind the robbery. Apparently, the glasses wearing O'Keefe had kidnapped another member of the gang, Vincent Costa, and had demanded his part of the loot for ransom. Eight living gang members received life sentences though Specs was paroled after just four years. Only about $58,000 of the $2.7 million was ever recovered. The rest is supposedly hidden in the Midwest somewhere. Hopefully, the Gardner Heist will be better resolved.

The Gardner Heist seems to be stuck in an investigatory quagmire. There are whiffs of clues, missed directions and a whole circus of underworld characters. Interpol has been involved for years in the case. Art sleuths of every variety have added their two cents (or two Euros?) to no avail. Overly dramatic, nineteen years later, the empty frames remain on the walls due supposedly to the codicil of not changing anything in the museum from the time of Mrs. Jack Gardner's death or the ownership of the palazzo and everything inside reverts to Harvard University. Didn't the thieves change things 19 years ago?

Where are Holmes and Watson, Miss Marple, Hercule Poirot, Father Brown, Supt. Dagliesh, or even Inspector Morse when you need them? In nearly two decades, no one in the underworld has talked. The quiet is disconcerting, especially in a blabbermouth town like Boston. This is very strange. It is an odd, no very peculiar case. What should be done besides calling out The Baker Street Irregulars?

Perhaps, it is time for the Gardner Museum to lighten up a bit. Rather than continue to grieve, it is time to celebrate the greatest art robbery in the world. The Gardner Museum should issue digital games exploring the robbery in all of its aspects. It would be sort of a Grand Theft Auto approach to finding solutions to the case. A board game for the less digitally minded could be a version of Clue. Maybe, an Encyclopedia Brown methodology could be taken where the players have to solve the mystery themselves? The money generated by the sale of these games could result in additional reward money or even the purchase of great, hopefully not stolen, art. Maybe the case will actually be solved through this crowdsource approach. One thing is for sure, however, the butler didn't do it.