Whitney Biennial 2010

Evaluating Its Impact Since 1932

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 18, 2010

Whitney Biennial 2010Curated by Francesco Bonami and Gary Carrion-Murayari

Catalogue: Forward by Adam D. Weinberg, essays by Bonami and Carrion-Murayari, artists in the exhibition texts by: Nicole Cosgrove, Hillary deMarchena, Diana Kamin,Tina Kikielska, Fionn Meade, Margot Norton,William S. Smith Checklist of the Exhibition, Appendix, 2008-1932, 264 pages, ISBN 978-0-300-16242-4 Distributed by Yale University Press.

The Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Avenue

New York, New York, 10021

February 25 to May 30, 2010

The Artists:

David Adamo, Born 1979 in Rochester, New York; lives in Berlin, Germany;

Richard Aldrich, Born 1975 in Hampton, Virginia; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Michael Asher, Born 1943 in Los Angeles, California; lives in Los Angeles, California

Tauba Auerbach, Born 1981 in San Francisco, California; lives in New York, New York

Nina Berman, Born 1960 in New York, New York; lives in New York, New York

Huma Bha,,Born 1962 in Karachi, Pakistan; lives in Poughkeepsie, New York

Joshua Brand, Born 1980 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Bruce High Quality Foundation, Founded 2001 in Brooklyn, New York

James Casebere, Born 1953 in East Lansing, Michigan; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Edgar Cleijne and Ellen Gallagher, Born 1963 in Eindovern, The Netherlands/Born 1965 in Providence, Rhode Island

Dawn Clements, Born 1958 in Woburn, Massachusetts; lives in Brooklyn, New York

George Condo, Born 1957 in Concord, New Hampshire; lives in New York, New York

Sarah Crowner, Born 1974 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Verne Dawson, Born 1961 in Meridianville, Alabama; lives in Saluda, North Carolina, and New York, New York

Julia Fish, Born 1950 in Toledo, Oregon; lives in Chicago, Illinois

Roland Flexner, Born 1944 in Nice, France; lives in New York, New York

Suzan Frecon, Born 1941 in Mexico, Pennsylvania; lives in New York, New York

Maureen Gallace, Born 1960 in Stamford, Connecticut; lives in New York, New York

Theaster Gates, Born 1973 in Chicago, Illinois; lives in Chicago, Illinois

Kate Gilmore, Born 1975 in Washington, DC; lives in New York, New York

Hannah Greely, Born 1979 in Los Angeles, California; lives in Los Angeles, California

Jesse Aron Green, Born 1979 in Boston, Massachusetts; lives in Boston, Massachusetts, and Los Angeles, California

Robert Grosvenor, Born 1937 in New York, New York; lives in Long Island, New York

Sharon Hayes, Born 1970 in Baltimore, Maryland; lives in New York, New York

Thomas Houseago, Born 1972, Leeds, England; lives in Los Angeles, California

Alex Hubbard, Born 1975 in Toledo, Oregon; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Jessica Jackson Hutchins, Born 1971 in Chicago, Illinois; lives in Portland, Oregon

Jeffrey Inaba, Born 1962 in Los Angeles, California; lives in New York, New York

Martin Kersels, Born 1960 in Los Angeles, California; lives in Los Angeles, California

Jim Lutes, Born 1955 in Fort Lewis, Washington; lives in Chicago, Illinois

Babette Mangolte, Born 1941 in Montmorot (Jura), France; lives in New York, New York

Curtis Mann, Born 1979 in Dayton, Ohio; lives in Chicago, Illinois

Ari Marcopoulos, Born 1957 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands; lives in Sonoma, California

Daniel McDonald, Born 1971 in Los Angeles, California; lives in New York, New York

Josephine Meckseper, Born 1964 in Lilienthal, Germany; lives in New York, New York

Rashaad Newsome, Born 1979 in New Orleans, Louisiana; lives in New York, New York

Kelly Nipper, Born 1971 in Edina, Minnesota; lives in Los Angeles, California

Lorraine O'Grady, Born 1934 in Boston, Massachusetts; lives in New York, New York

R. H. Quaytman, Born 1961 in Boston, Massachusetts; lives in New York, New York

Charles Ray, Born 1953 in Chicago, Illinois; lives in Los Angeles, California

Emily Roysdon, Born 1977 in Easton, Maryland; lives in New York, New York, and Stockholm, Sweden

Aki Sasamoto, Born 1980 in Yokohama, Japan; lives in Brooklyn, New York

Aurel Schmidt, Born 1982 in Kamloops, British Columbia; lives in New York, New York

Scott Short, Born 1964 in Marion, Ohio; lives in Chicago, Illinois

Stephanie Sinclair, Born 1973 in Miami, Florida; lives in New York, New York, and Beirut, Lebanon

Ania Soliman, Born 1970 in Warsaw, Poland; lives in Basel, Switzerland, and New York, New York

Storm Tharp, Born 1970 in Ontario, Oregon; lives in Portland, Oregon

Tam Tran, Born 1986 in Hue, Vietnam; lives in Memphis, Tennessee

Kerry Tribe, Born 1973 in Boston, Massachusetts; lives in Los Angeles, California, and Berlin, Germany

Piotr Uklanski, Born 1968 in Warsaw, Poland; lives in New York, New York, and Warsaw, Poland

Lesley Vance, Born 1977 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; lives in Los Angeles, California

Mariane Vitale, Born 1973 in New York, New York; lives in New York, New York

Erika Vogt, Born 1973 in East Newark, New Jersey; lives in Los Angeles, California

Pae White, Born 1963 in Pasadena, California; lives in Los Angeles, California

Robert Williams, Born 1943 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, lives in Chatsworth, California

In its past incarnations there have been efforts to redefine what started as the Whitney Annual in 1932. Initially, there were thin publications which expanded and become more complex through the decades. Reflecting art world tendencies some of the past few catalogues, for what evolved into the Whitney Biennial, took on an independent identity as works of art in and of themselves.

Part of the dialogue of self examination cuts to the very name of the institution; The Whitney Museum of American Art. It begs that perennial question of what is American about American Art? To evoke Bruce Springsteen does that mean "Born in the USA?" Or will a green card suffice? With the development of Globalization does that include having a presence on American soil? Another trope has been to define American as the Art of the Americas. By that approach it opened the work of artists of two continents for inclusion in the Whitney Biennial. The initial curatorial decision was to penetrate immediate borders by showing a a few artists from Mexico and Canada.

Back in 1932 a mandate for the founding of the museum was to promote the contemporary art of our nation. In its earliest incarnation work was shown in a town house setting. The struggling institution became a step sister to the Museum of Modern Art, founded at about the same time. MoMA focused on European Art with a bias for the School of Paris.

Curiously, MoMA tended to underplay Germanic art. That work was espoused by the Busch Reisinger Museum of Harvard University and the Boston Museum of Modern Art. Initally, BMoMA was a branch of MoMA in New York. Under its director, James Plout, largely through dissent regarding French vs. Germanic focus, the museum famously revolted and reinvented itself as Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art. It also decided to be a kunsthalle rather than a museum with a permanent collection. That policy has changed only in the past couple of years.

For its first decades the Whitney fought the good fight. Compared to the European avant-garde American art was viewed as small beer and provincial. Then there was what critic Irving Sandler has chronicled, after WWII, as The Triumph of American Art. The loaded word Triumph implies that there was an aesthetic war or combat. It was in a sense a bloodless but effective revolution. As Marxist historian, Serge Guilbaut, postulated in How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art. The chief advocates of this development and most widely read critics were Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg.

During its early years there was a close relationship between the Whitney and MoMA. For a time the Whitney was a small appendage of MoMA. It was in effect its American Wing. Eventually, the Whitney relocated, in 1966, to its current location in a building designed by Marcel Breuer.

This eventual physical separation also allowed MoMA to redefine its relationship to American Art. In 1956, Dorothy C. Miller, the director of exhibitions, organized 12 Americans. She wrote that "Twelve Americans, 1956, is another in a series of exhibitions held periodically at the Museum of Modern Art since the first year of its existence. These exhibitions, devoted to contemporary American art, were designed to contrast with the usual large American group shows representing a hundred or more artists by one work each. From the many distinguished artists who might have been included in this exhibition, an arbitrarily limited number was chosen, so that each might have a separate gallery for his work. The character and quality of individual achievement can more readily be grasped under these circumstances.

"Like its predecessors in the series Twelve Americans emphasizes differences rather than similarity, bringing together artists who vary widely in approach and technique. Though several have been associated with the movement known as abstract expressionism, no single style or theme runs through the exhibition; it presents a group of distinct individuals in small one man shows loosely bound within the framework of today's major preoccupations in the arts. To illustrate trends was not the purpose of the exhibition."

Reading between the lines Miller's 12 Americans was presented as an alternative to the sprawling Whitney Annuals. She was in essence saying here are the really good ones. Why? Because, MoMA says so. The legacy of curators and critics resides in their ability to pick the winners. In the art world there are many images of war, combat and sport. The artists shown by a gallery, for example, are referred to as its stable. Evoking sleek and swift race horses. Its contenders and champions.

If Miller and MoMA are regarded as having the "best eyes" of their generation it is interesting to list the artists included in the 1956 exhibition: Ernest Briggs, James Brooks, Sam Francis, Fritz Glarner, Philip Guston, Raoul Hague, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Ibram Lassaw, Seymour Lipton, Jose de Rivera and Larry Rivers.

It is indeed an interesting list. Although Miller's essay states "his work" there is one woman, Grace Hartigan. That the curator was female, and did not make the gender change in the essay, is an indicator of the glass ceiling that dominated her generation. In the current Whitney Biennial 2010 of the 55 artists shown, for the first time, there are more women than men.

Commenting on this in his New York Magazine review Jerry Salz states that "It is also historic: For the first time, there are more women included than men. How thrilling and important this is shouldn't be overlooked or treated cynically, because this biennial isn't about women's art, feminism, or affirmative actionÂ…"

Of the twelve artists selected by Miller how many have endured? The "winners" would appear to be Kline, Guston and Rivers. That's three out of 12. The remaining nine are known to experts and because of gender politics a case is made for Hartigan. I recall an exhibition on Brooks mounted by Sam Hunter early on at the Rose Art Museum. During the recent New York Art Fairs there was a booth devoted to his work. Second and third tier abstract expressionists are being resurrected by the art market and graduate students seeking dissertation topics.

Of the twelve in Miller's show the best regarded artist is Guston. But not for this work which was from his abstract expressionist phase. He was largely reviled by the art world establishment when he returned to figuration in his late work.

For a time Guston commuted to teach weekly at Boston University. He made contact with the Museum of Fine Arts and offered them a painting. The tale is told that the MFA requested one of the early works and was not interested in the figurative paintings. The Guston that entered the collection, decades later, was not a gift from the artist.

Three years later Miller curated Sixteen Americans which included J. De Feo, Wally Hendrick, James Jarvaise, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Alfred Leslie, Landes Lewitin, Richard Lytle, Robert Mallary, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, Julius Schmidt, Richard Stankiewicz, Frank Stella, Albert Urban and Jack Youngerman. Here her batting average has improved. Of the 16 the seven who have slipped into obscurity are Hendrick, Jarvaise, Lewitin, Lytle, Mallary, Schmidt and Urban. De Feo has been resurrected in the past decade. The Whitney now owns her restored masterpiece "The Rose" which was featured in its Beat show.

For Americans 1963 Miller selected Richard Anuskiewicz, Lee Bontecou, Chryssa, Sally Hazelet Drummond, Edward Higgins, Robert Indiana, Gabriel Kohn, Michael Lekakis, Richard Lindner, Marisol, Claes Thure Oldenburg, Ad Reinhardt, James Rosenquist, Jason Seley, and David Simpson. Of the 15 artists Miller included four women. Anuskiewicz would be featured in MoMA's Responsive Eye exhibition in 1965. Reinhardt was also a step in that direction. For the rest of the selection Miller hedged her bets supporting pop art. Which gave her a twofer in Marisol. Of her fifteen, among the missing today would be Drummond, Higgins, Kohn, Lekakis, Seley and Simpson. There is a market for the fetish paintings of Lindner but his reputation has eroded with time. So with this show Miller batted roughly 500 which is pretty good in any league.

By now the reader has the right to ask when we will get to the Whitney Biennial 2010? Why all this history?

Actually, this approach is very appropriate to the current Biennial. While the Biennial has been scaled back for a plethora of reasons- lousy economy, recovery, retrenchment, an aesthetic decision- the approach of the curators, Francesco Bonami and Gary Carrion-Murayari, even with 55 artists, it is closer to the paradigm of Miller's MoMA projects than the usual Whitney circus of more than a hundred artists. This is the most concise, coherent, and orderly Biennial we have seen in decades.

Instead of a project that everyone loves to hate, with the exception of the Australian born, Boston Globe critic, Sebastian Smee, who has little or no history with the Whitney Biennial, this project has universally been damned with faint praise. Not that I dissent. But sorting it all out there is the usual challenge of fixing on work that has left a profound and lasting impression. Works with the strongest initial impact may prove to be the most ephemeral. It is usual that work which evades us initially may return during a later cycle of exhibitions.

Coming back to those art world analogies about combat and horse races it is the perceived job of critics to pick the winners and losers. Some are very skilled at this exercise, have vaunted reputations, or write for major publications. It is not within our ability or intention to compete with that.

One of the most significant aspects of the development of on line criticism is that it has allowed for a greater range of voices, viewpoints and approaches. It allows for, indeed encourages, following the path less taken.

The 2010 Biennial mandates, a reflective, more art historical overview. It is embedded in all aspects of the exhibition. The top floor of the Whitney, where one normally finds the permanent collection, has been reinstalled. From all of its annuals and biennials the museum has purchased a few works. A selection of these acquisitions combining well know as well as now forgotten artists proves to be stunning and insightful. It is one of the most compelling sidebars to a major exhibition ever installed by the museum. This overview of the past sets the mood for the current event. We urge you to start there and then work your way down.

Also this proves to be one of the best organized Biennial catalogues. Its most useful and enduring feature is an appendix of all of the previous annuals and biennials including the complete list of exhibited artists and curators. It is an invaluable scholarly resource. There is also a fascinating selection of reproductions of reviews. They are facsimile clippings, or cuttings, of New York Times essays. Under different bylines it is interesting to note that the same points, with different examples, are made repeatedly.

In 2006 Michael Kimmelman wrote that "Â…This typically huge exhibition is very much an insider's affair, a hermetic take on what has been making waves. It will seem old hat to aficionados and inscrutable to many othersÂ…" In 1993 Kimmelman wrote "I hate the show. I had hoped after some weeks had passed and the smoke had cleared, to discover some gems left in the rubble. But it turns out I became increasingly depressed by the exhibition, partly because of the few good works in itÂ…"

On Hilton Kramer's watch he wrote "It will hardly be a surprise to anyone, I suppose, to hear that the 1977 Whitney Biennial Exhibition, now occupying the bulk of the gallery space at the Whitney Museum of American Art, is an unbelievable bore. Most of us have learned-oh how we have learned- to expect little or nothing from these periodic attempts to summarize what is happening in contemporary American artÂ…"

Reporting on the 1969 exhibition John Canaday stated "Some shows have been majestic, others ludicrous. But in all these ten years and thousands of shows, I have never before come upon one, until this year's Whitney Annual, that was truly and profoundly and altogether disheartening. So much of it is so bad it breaks your heart for American paintingÂ…"

In 1944 Edward Alden Jewell was upbeat. "In any event, however compounded, the Whitney Annual proves to be a stimulating affair throughout. That is because it contains so much work that is truly excellent, without respect to theme." In 1934 for the second Annual Jewell stated that "There isn't a dull room in the building. Each wall is an adventure. Taken as a whole, the exhibition can leave few visitors doubting that we have in this country an art that deserves to be called our own; an art full of courage in the face of handicap; an art that is in many respects robust and imaginatively progressive. There are no signs of the depression hereÂ…"

From Jewell's remark in 1934 "There are no signs of the depression hereÂ…" we appear to have come full circle to what critics are saying about the current project. It is impossible to ignore that this down scaled, more concise, benign project is reflective of the economy of what has been dubbed The Great Recession. We are also in the midst of the Obama era. This point is made emphatic by including an image of the president, cast in green and wearing a felt hat, in the upper right corner of the catalogue cover. It is then telescoped four more times in decreasing scale. This design concept is repeated eight more times in the center of the book. The cover design is repeated on cover stock, with the center of four nested squares, containing decades from 2000 to 1930.

Even in this most simple and straight forward catalogue, praise the Lord, there is a quibble with the designer. It seems such a waste to have this indulgence. It beats the idea to death. Adds expense and took away from other options. For example, more room might have been devoted to reproductions and text for the individual artists. The portfolio of dismal covers makes the book awkward to handle. It is, however, an improvement on the 2006 catalogue which self destructed after light handling.

In past Biennials it has been usual to calculate just how many artists are represented by the leading New York galleries. Or appeared to be on the dinner party circuit with the curators. One also felt the shadow of collectors and their influence. Money has always played a role in the taste and trends of museum exhibitions.

Today there are more galleries than ever, despite the recent thinning of ranks. But there is a greater proportion of contemporary work which is difficult if not impossible to market and sell. A generation or so ago that described artists making earth works. By definition the artists expended beyond the urban environment and outgrew galleries and museums. But there were strategies that conformed to the expanded needs of the art market. Christo and Jeanne Claude-Claude, for example, raised funds for their temporary, site specific works by selling plans and drawings.

The Dia Foundation maintains a number of permanent installations such as the 1977, Walter De Maria, Lightning Field at Quemado, New Mexico, which is about a 2½- to 3-hour drive from Albuquerque, New Mexico. We make pilgrimages to the The Chinati Foundation founded by the sculptor Donald Judd on an abandoned air force base in Marfa, Texas.

Artists emerging from graduate programs have nursed on the mother's milk of philosophy, feminism, queer studies, conceptualism, minimalism, installations and video. It is ever more difficult to gather all those critters into a net. Nor do they want to.

Career ambitions have taken on new dimensions. These young artists have been trained to look beyond galleries and museums. They set their sights on the international circuit of mega exhibitions and biennials. Artists who succeed at that level maintain studios with teams of technicians and specialists. They function less as individual artists and increasingly like independent filmmakers. Following the model of Jeanne-Claude and Christo the artifacts and ephemera of their projects find their way into the booths at art fairs.

What then is the Whitney Biennial 2010? Well, all and none of the above. There is a fair slice of gallery art. More painting and work on paper, in the usual sense, than we have seen in some time. In 2010 it seems OK to paint if you find the right niche. There seemed to be a lot of geometric abstraction and minimalism, a touch of irony, hint of expressionism, dash of fantasy, no hyper realism, with just a bit of bad art.

Mostly we sensed that this Biennial was painstakingly thought through and sorted out. Whatever you concluded about the work there was the feeling that the curators made every effort to present the work with utmost fairness and precision. We rarely felt that we were backing up from one work to get a better look at another. Or that the sound and light from one installation were interfering with another.

Even the ubiquitous videos were separated out to its own floor in a maze of mini theatres. We worked our way through a series of cubicles. These varied in dimension and may or not include benches.

There was a refreshing sense of breathing room particularly as we visited during a week day afternoon. We viewed the work under ideal conditions allowing enough time and space fully to appreciate the individual works as well as its cumulative impact.

Even in this Biennial which was fair, low key, and Obamaesque to a fault there are implied ground rules. There were artists, such as Lorraine O'Grady (born, 1934) arguably included for lifetime achievement. She displayed a series of three, photographic diptychs pairing Charles Baudelaire and Michael Jackson during comparable phases of their lives. She shared a fairly deep narrow space with a vintage limousine by the collective Bruce High Quality Foundation. Their piece reflected on the only visit of Joseph Beuys to New York and his performance with a Coyote I Like New York and New York Likes Me. A collage of images was reflected in the windshield.

The eclectic artist Charles Ray, who was shown in prior Biennials, returns with a room of large format watercolors of flowers. Were they created by any other artist it is doubtful that they would be given such a formidable space in this exhibition. They could not have been presented under better circumstances. But.

The same might be said of the generous display of a sculpture by Robert Grosvenor (born 1937) a respected artist revived for this occasion. Through a fence of metal circles we look beyond to a padded, red, bridge like structure. It is meant to be viewed for its components and their separate impressions of color, texture and material. This was strong and intelligent work with a firmness of conviction. In this project there was no cacophony to contend with in absorbing its elegance and understatement.

When we look back at 2010 and its Biennial future generations will ask how art reflected the Age of Obama and its two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He didn't start them but their horrors continue under his watch. This is noted by work from two photographers, both horrific. Nina Berman records the tragic love between the grotesquely damaged Marine sergeant Ty Ziegel and his high school sweetheart Renee Klein. Stephanie Sinclair exhibits documentary photographs of women in Afghanistan who out of brutal desperation have mutilated themselves through self-immolation.

Through shock value the works by Berman and Sinclair were the most riveting in the Biennial. They were gut wrenching to view and the experience fails to slip away. But it begs the question of just why they were included in this biennial survey of art? They would seem more appropriate for an exhibition of documentary photography. It is significant that the series by Berman was commissioned for People Magazine. The assumption is that the intention of the photographers was not to make art. The curators made that decision. In so doing they passed over many artists working with aspects of war, genocide, and terrorism. Shouldn't we consider war beyond the lens of the straight photographer?

The day after visiting the Biennial was viewed the Otto Dix exhibition at the Neue Gallerie. There we encountered his portfolio of 50 prints War. They were published in an edition of 72. It is the greatest treatment of the topic since Goya's The Disasters of War. Dix spent three years heading a machine gun squad in the German army during World War I. He knew first hand the gruesome carnage he depicted. While the images documented what he experienced the work is a part of the canon of art.

We were also fascinated by a documentary film installation by Kerry Tribe. On a split screen her work explored the short term memory loss of H.M. He was given experimental brain surgery to cure epilepsy. While he appeared capable of recalling memory from before the surgery for events following treatment his memory span is limited to twenty seconds. The topic was absorbing enough to view the entire piece.

A number of the other video installations, for a variety of reasons, we were content to sample. A black man voguing, by Rashaad Newsome, was interesting but not a subject that I particularly relate to. The video by Ari Marcopoulos was too loud and something about kids playing with sound gadgets. Oh well. I just lacked the patience to figure out what the multiple projections by Sharon Hayes added up to. And what was the point of the men on platforms doing gym exercises by Jesse Aron Green? Please send Marianne Vitale back to graduate school for another semester.

Boston Globe critic, Smee, went ballistic over the sculpture by Jessica Jackson Hutchins. She has papered a couch with newspaper coverage of Obama. How timely. On top of the couch are two funky, primitively created earthen jars. They are crude to a fault. While I hedge on what it all means the piece held my attention and is among the more memorable works in the show.

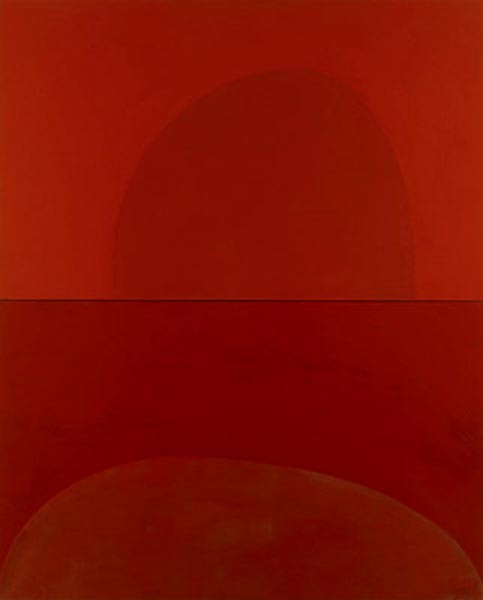

While painting was well represented it proved to be unremarkable. The best work was a combination of thin, glazed, abstract mark making over figurative elements by Jim Lutes. The reductive abstract forms with narrowly defined chroma by Suzan Freeon, while meticulously rendered, add little or nothing to an approach with many exponents.

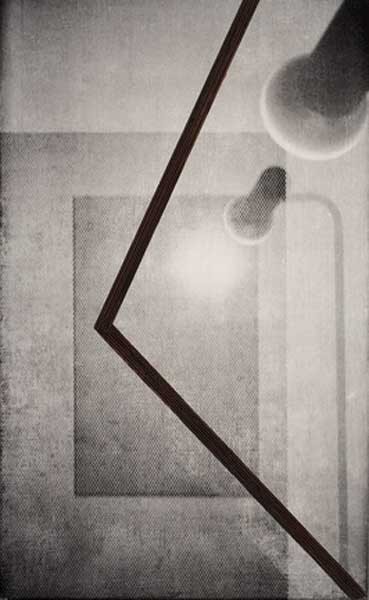

There are of course artists whose work I have ignored or perhaps embraced overly enthusiastically. One might note, for example, that I failed to mention the bronze lumpen proletariat, in every sense, of George Condo, or the setup studio shots of invented architecture by James Casabere. Or how much I really hated the room by Edgar Cleijne and Ellen Gallagher.

Nobody wants to be remembered like my former colleague, Ken Emerson, for trashing the debut James Taylor album for Apple Records. It is now viewed as a classic. Then again I praised the first Cat Stevens album. Oh well. Who's keeping score?

Holland Cotter New York Times Review

Jerry Salz New York Magazine

Blake Gopnick Washington Post

Sebastian Smee Boston Globe

Christina Viveros Faune Village Voice

Kriston Capps The Guardian

Charlie Finch Art Net