Ric Haynes: Children of the Empire

Exhibition at Boston's Hall Space

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 23, 2012

Ric Haynes

Children of the Empire

HallSpace

950 Dorchester Avenue

Dorchester, Mass. 02125

617 288 2255

March 17 through April 21, 2012.

The narrative paintings of Ric Haynes have long represented for me an absorbing, daunting, and perhaps, horrific or at least poignantly empathetic response.

To understand these intense and galvanic images, which I would never assume, would entail imbibing of the Eat Me/ Drink Me potions required to navigate the rabbit hole leading to a wonderland of semiotics and archetypes.

It is beyond my stamina and insight to keep up with Haynes who has spent a lifetime of exploring sources in fine arts/ surrealism, Jung’s work on symbols and archetypes, the myths and rituals of Native American culture (in particular his close associations with the Crow people), the global anthropology and mythologies which we glean from Joseph Campbell and other sources.

This search reaches beyond the academic, although it informed his former pursuit as an expressive art therapist, and more recently, after receiving an MFA degree for a professional change, teaching the fine arts. The creative result of his professional life is reflected in the unique work. But it expands far beyond intellectual curiosity.

The paintings which are so rich, fascinating and sumptuous may be considered as the artifacts of a personal journey. Native Americans would describe this in terms of a totemic vision quest. Traditionally, it is an adolescent ritual and rite of passage. It is a means of bonding with the spirits of the natural world to form a totem, persona, and spiritual ally/ protector.

As Melville wrote “Call me Ishmael.”

Those who take this quest beyond a discovery and naming of self are regarded as shamans or medicine men. Although he is a friend and brother to a tribe, as a non native, however simpatico, Haynes is denied status as a shaman. So the alchemy at work in the paintings is entirely private making no claims to healing others. Engaging with the work and exploring its iconography, however, evokes a healing process. It is possible to apply what we derive from the work as metaphors for our own individualism and humanism.

In our mainstream, non traditional world, the shaman is arguably a doctor or therapist. Perhaps by default, for a time, Haynes worked with clients. It was a part of his initial relationship with the Crow people. For a number of reasons that pursuit ended. Teaching art to undergraduates was perhaps less ensnaring.

Arguably, the logical conclusion of this line of thought is that therapy, self healing, continues in the paintings. But that is a very limited analysis which Haynes navigates deftly in the statement below. It is perhaps a reflection of our vulgarity and lack of intellectual acumen that we want to apply some pop psychology to unlocking the mysteries of Bosch, Munch, van Gogh, or Dali.

Dr. Phil is not the right approach to understanding a work of art. Imagine having him explain the Tibetan Book of the Dead or I Ching. Between commercials.

And yet, this is the most common approach to coming to grips with works of art that shake our soul or lead us into the labyrinth and endless doors of the Magic Theatre. Most of us have a rich and complex dream life, which sadly for me, snaps back to reality with first light.

In that sense the remarkable and enthralling works of Haynes are lucid dreams. The specters of night and the subconscious that manage to remain vivid and haunting through the light of day.

Artist Statement

I paint every day and feel that my process is to reveal all the content of my interests in history and myth and to rediscover that material by my working. I practice several ways to maintain a stream of images and find that prolific images emerge. I am often asked where do my images come from? The images in my paintings and drawings form, as they do in our dreams, from fragments of things I read, see in real life experience, as well as images integrated with dreamscapes that combine both reality and fantasy. I regard my image content as stories that need to be told, as well as those that need to be explained.

Fantasy is often regarded as being in the realm of “inner stuff” and working out therapeutic issues. Sometimes people mistakenly presume that I am giving them tragic, complex and intricate material to decipher. However if they asked me, I would tell them my themes are about redemption, escape from entrapped situations and always going off to a better place. I am interested in the act of leaving home, leaving the old traditional values and striking out into new territories. Always the family romance of finding different and better parents is involved. In many cases the children turn out to be caretakers of their own souls.

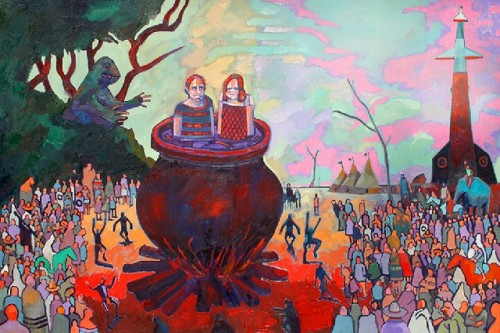

In "Bounty" the boatload of children being carried off by a group of worried cannibals is really not about abduction or cannibalism but the question of who is being captured. The children are carried away to become members of a tribe that needs additional members, while those children are already planning their escape by the use of their own autonomy. In "Trouble" the children are being boiled in a pot while their captives joyously dance about. Despite the seemingly dire outcome, the scene instead is about the planned escape that the children are plotting. Once the dinosaur is fully on the scene, the dancing villagers will run away and the children roll the pot over and escape.

I am intrigued about what is in the backyards of farmhouses. What would the space program look like if idle farmers designed the rockets? Then who would go into space -- the bad child, the unappreciated, or the soul looking for a better place to dwell? The rockets in these paintings represent these yearnings. In my childhood the trash of someone else’s backyard became treasures to my own imagination. All kinds of things were in those back yards, and in one way those backyard items could substitute for the unconscious. In "Shooting Star" I imagined that a cannon is shooting someone into the atmosphere, leaving behind backyards filled with iconic objects of varied scale, size and meaning from their past.

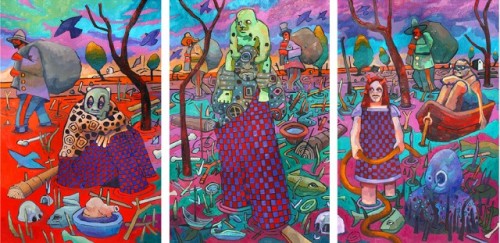

In "First Light" the children are born from a giant pod, and still remained attached to that pod. It was an accident that the cords were developed tying the children to the pod. In a sense my thinking about breaking away from the parent was the basis for the themes of these paintings. I labored over the painting of the children in this work and it later turned out that those children, “born” in that painting became the foundation characters in this series.

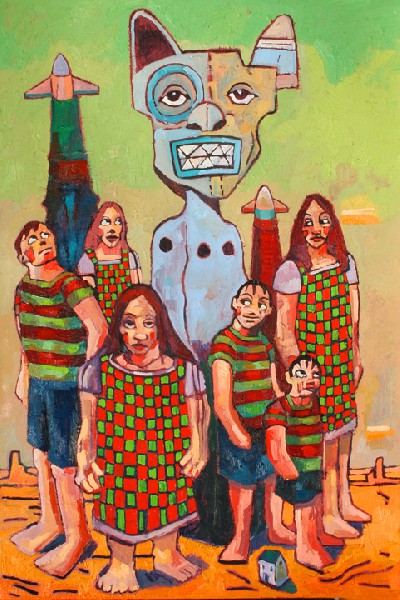

In "Backyard Giant Children" the children become objects outside of their own human scale and take on a persona of being built in the backyard. In "Awe" the children are questioning a masked figure that they suspect may just be an older child. It is a bit like the masked dance societies throughout various cultures who show the child that the figure behind the mask is a regular person like them.

The largest and most daring story of this series is found in "Dangerous Mission.” It is about rescue and the consciousness of bringing children into the world while the historical world is amuck with chaos and debris. The girl is pulling a boat with a masked character in it, while on the far left another masked figure sits amongst the debris and contemplates the scene. The checked pants and skirts are like uniforms of kindred spirits who know a similar language and therefore are members of the same understanding and promise for the future. Meanwhile, veterans from past wars and times are carrying large bags of things that must be saved from these vanishing civilizations being left behind. The bags have the treasures of the beginnings of new life in them. Anytime I paint bones and skulls in a painting it refers to history or things that have gone before.