Tanzania: Part Three

Olduvai Gorge and Serengeti National Park

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 23, 2012

From the Highlands, taking in views of the crater below, we journeyed to Olduvai Gorge in the Ngorongoro Conservation Unit. It was here, in 1959, that Louis and Mary Leakey discovered fossil fragments, including a skull, which led them to a new understanding of animal and human evolution. Then in 1978 at Laetoli, just south of Olduvai, Mary Leakey found footprints of three upright-standing hominids in compacted volcanic ash, which had powdered the plains 3.7 million years before. The weathered area looks like as if early man lived here only yesterday. A small museum displays renderings and photographs explaining the Leakeys’ methods and findings, such as hyperion (three-toed horse) tracks and hominid trails, both about 1.8 million years old.

More recently, the original modern human inhabitants of what is now Tanzania were hunter-gatherers. Other tribes gradually moved in, seeking better land and displacing or absorbing the aborigines. The newcomers were members of Bantu tribes entering from the western lake region. By 1300 AD they had spread into the areas of heavy rainfall, leaving the plains to Nilo-Hamitic pastoralists, such as the Masai, who descended later from the north.

The Serengeti, where the southern plains seem to stretch to the horizon (hence the Masai name “Siringet,” meaning “endless space”), is Tanzania’s first and largest national park. It was established in 1951 by dividing the plains into Ngorongoro in the south and Serengeti National Park in the north. In 1959 the Masai were relocated outside of the park, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981. In the same year it was declared, together with Ngorongoro, a Biosphere Reserve to preserve the ecological integrity of the area.

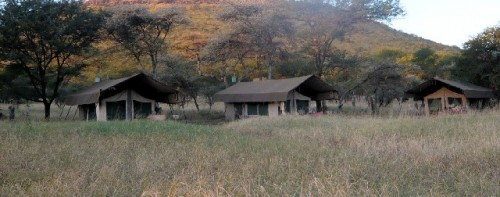

Covering an area of 14,763 square km, as big as Northern Ireland, the Serengeti is set on a high interior plateau, ranging from 900 to 1800 meters above sea level. With Masai women and children waving to us outside the gate, we entered the park. As we drove across the vast plain to reach our remote camp, the splendid scenery was a stage set for wildlife, especially for giraffes, which looked majestic in the grassland without competition from nearby trees. We arrived at the camp, where the air was full of birds soaring, sweeping, and singing around the tents. Birds in brilliant blues, greens, and yellows perched nearby the verandah, with its canvas washbasin, of my large walk-in tent, which was to be my home for the next four nights.

Unlike our previous camps, this was a mobile camp in a designated area of the park, called Simba. The camps are moved around, both for ecological reasons and because of their proximity to the routes of migrating animals. Around the dining tent, acacia trees, silhouetted against the setting sun, graced the evening sky. At night I fell asleep to the wailing of hyenas and woke up with the cheerful delivery of a bucket of hot water, which I acknowledged with “asante” (thank you) “sana” (very much), thus starting my birthday in Kiswahili — a language derived from Bantu and Arabic roots.

Our day’s itinerary began at the park visitor center. From here a 30-45-minute walk took us up a trail through the sights, sounds, and smells of the splendid natural setting, while we learned about its variety and abundance, depicted on attractive signs. Although wildebeest and zebras are both herbivores, they eat different types of grasses; the former feeds only on high-quality short grass or tall grass that has been trimmed by zebras. Therefore, the two species travel together. The dry season (June-October) sets animals migrating from the southern plains to the northern woodlands. When the rains start again in November, the herds return south to calve, as new green growth provides essential nutrients for their young. Wildebeest have a synchronized calving period of three weeks, during which 8000 calves are born on average each day. To avoid predators, calves are on their feet in minutes, running at full speed within an hour. Most wildebeest calves are born in February; zebras are born throughout the year.

As we drove around, the migration spectacle unfolded before our eyes. Like a circus caravan, large herds of wildebeest and zebras, because of their shared need for water and fresh grassland, moved en masse toward the Seronera River. Respectful of each other’s space, they lined up at the water’s edge; bending their heads in synchrony, they drank non-stop to satisfy their thirst — an essential need they must meet every two-to-three days. Meanwhile, hippos cooled off in the river’s serene waters further down.

Gazelles and eland feasted on tiny shoots left behind by large migrating animals; ostriches walked about with a gentle gait in search of food; a baby baboon enjoyed a ride on her mother’s back, while bull elephants congregated around trees. Suddenly our attention turned to a lion which emerged from the tall grass, looking around intently, and walked over to a vacant termite mound, settling on it in the shade of an acacia to survey the surroundings from a high vantage point. Lions are territorial and prey on migrating animals as they pass by. Wildebeest and zebras are lions’ favorite food. During lean times they go after warthogs and calf. I felt fortunate not to be witnessing a killing on my birthday. However, we did spot a dead zebra placed by a leopard on a tree for safe keeping.

Our big prize of the day was sighting a leopard, which appeared to be asleep on a tree. Camouflaged by its spots, it blended in with the limbs of an acacia. Patience paid off; finally the leopard changed its lounging position to face us. Binoculars revealed a beautiful face. Cameras clicked non-stop, as if we were filming a movie.

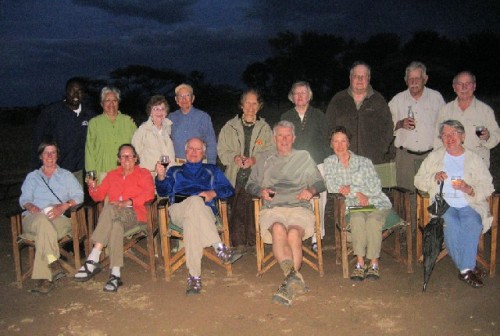

Back at camp for dinner there was another surprise birthday party. Following soup and the main course, the waiters processed into the dining tent, singing, clapping, and carrying a decorated cake with my name in the center and candles all around. My travel companions joined in the singing. Feeling grateful to begin my fourth quarter-century in the presence of such joyous company, I made a wish and blew out the candles. The cake, served by the staff, was enjoyed by all.

During the night strong winds howled outside my tent. I got up to close all the flaps and went back to sleep, hoping that the winds would not affect the optional hot air balloon ride at sunrise which I had signed up for — a last-minute decision. After experiencing the Serengeti on the ground, I felt compelled to see its immensity from the air.

In the morning calm I was awakened very early with my hot water delivery, and was picked up at 4:30 so as not to miss the sunrise. As the only adventurer from the Simba camp on that day, I did not know any of the riders in the jeep, and was unable to discern their faces in the dark; I could tell from the various accents that they were all European.

Shifting my attention between the spectacular sunrise and the inflating balloon, I tried to photograph both. Unlike my previous experiences, the balloon lay on its side until lift-off; we entered the basket in a horizontal position on our backs. The basket had four compartments, each holding four passengers, with sixteen people all together. Once the pilot righted the balloon, we began drifting over the Serengeti Plains with a unique treetop view. As I had hoped, thousands of animals flooded the plain. We hovered over the ground so close that I could literally count the stripes on the zebras’ backs. The hippos looked like a chain of islands in the river.

Upon landing we lined up to use the outdoor restrooms, which had a mountain view but no doors. Nearby a woman attendant poured water from a shiny copper pitcher over a basin to wash our hands, and handed out towels. This luxury was followed by a champagne toast, as has been the custom since the first balloon ride in France, when the king invited 400 friends to celebrate the launch. Before the toast the captain — an Afrikaner — asked if anyone among us had an anniversary or birthday to celebrate. Since nobody responded, I mentioned that my birthday had been the previous day. He suggested raising a toast to me, and led a crowd of 40 people in singing “Happy Birthday,” making this the third birthday toast of my trip. All the participants received Serengeti Balloon Safaris certificates, followed by an “Out of Africa”-style full English breakfast served under acacia trees, where I made friends with a German family.

On the way back to the visitor center, where I was to rejoin my group, the driver slowed down, pointing to a zebra giving birth under a tree. All heads turned; there was mama zebra with the baby’s head partially out. Nature’s wonders continued during the next game-viewing drive. Animals were feeding at every visible level — monkeys on trees, giraffes and elephants by tree branches, impalas and eland on the grass. A long-legged secretary bird enjoyed its food, sounding like a typewriter and thus justifying the name; storks reached for insects with their long beaks in the tall grass, while a lioness with young ones to feed blended into the golden grass, scanning for its next prey. A wildebeest calf, still light brown in color, followed its mother to pasture; nearby a turtle rested on the grass. Hippos contributed immensely to this great animal show, as several hundred of them lay partially submerged in a muddy pool of water, stacked against one another, and bobbing up and down in turn for air.

Kopjes (pronounced “copies”)— outcrops of ancient granite rock — are a most attractive feature of the park. Meaning “little heads” in Dutch, kopjes stand out as islands in a sea of grass. Broken and worn by constant expansion and contraction due to abrupt temperature changes, the ancient rocks have been shaped into sculptural forms, providing shelter for animals. White streaks of crystallized urine on some mark an active hyrax colony. Many of the rocks have trees growing out of them, thanks to collected water in their crevices.

During a visit to the Moru Kopjes, Ridas demonstrated how the large Gong Rock, when hit by smaller ones, rings out across the plains. There is a cave on another nearby kopje, with Masai rock paintings (relatively recent) by its entrance, depicting shields and figures. During this outing a cheetah, several spotted hyena, and more lions, including a male with its mane, crossed our path. The lions played on the road, literally in front of us; one lion climbed a tree to use it as a lookout tower. As we were driving back, our eagle-eyed guides spotted another leopard relaxing on a tree branch with his tail and paws hanging down, as if posing for pictures. We complied; thus satiated with the day’s excitement, we returned to the Simba camp for our final night.

Having enjoyed so many delicious meals at camp, we wanted to see the kitchen, and were amazed at its modest facilities. Working with very basic equipment in a tent, our cook was able to create a variety of dishes, often squatting over a wood fire to stir the pots. Thanking the camp staff for their attentive and cheerful service, we left for Ngorongoro to descend to the floor of the famed caldera on our way back to Karatu.