Paul Robeson Lives at BAM

The Tallest Tree in the Forest by Daniel Beaty

By: Susan Hall - Mar 24, 2015

The Tallest Tree in the Forest

Written and performed by Daniel Beaty

Directed by Moisés Kaufman

Music direction, incidental music, and arrangements by Kenny J. Seymour

Set design by Derek McLane

Costume design by Clint Ramos

Lighting design by David Lander

Sound design by Lindsay Jones

Projection design by John Narun

Dramaturgy by Carlyn Aquiline

Shelton Bectin (piano), Ralph Olsen (woodwinds), Marie Dorman Phaneuf (cello).

Tectonic Theater Project

Harvey Theatre

Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM

Brooklyn, New York

March 24, 2015 thru March 29, 2015

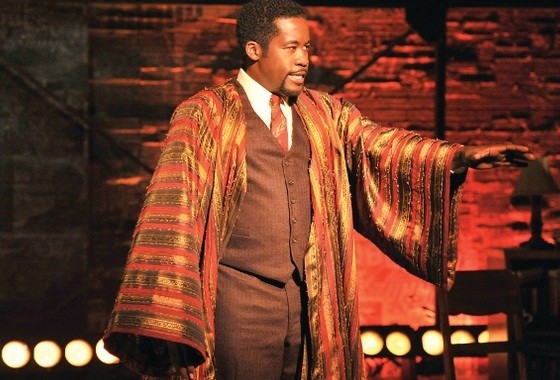

Daniel Beaty as Robeson emerges from pitch blackness with a richly re-imagined performance of Ol' Man River. The tone has changed. It is harsher, angrier than the original. Time has shown us that only a nigger can say nigger.

As the song is rough, so to the stage, an integral unit in the brilliantly rough-hewn Harvey theatre at BAM. Projections against the mottled wall will take us to the Cotton Club and Moscow, from the pre-Woodstock Peekskill where Robeson's career halted to streets of Berlin as Hitler rises. Spot lights in a warm orange/yellow are hung near the base of the stage and from the ceiling. A flutist, cellist and piano player accompany Robeson when he sings. The flute and cello are perched on risers at the stage rear.

Focus however is on Robeson the man, and a glorious human he was. Mary McCleod Bethune called him 'the tallest tree in the forest.' While he was chopped and hacked, he never fell. At the end, he disappeared, living silently in Philadephia with his older sister Marion.

Song fills the air, and it was song that impelled Robeson's career.

Beaty begins in Princeton, New Jersey, where young Paul spent his earliest years.

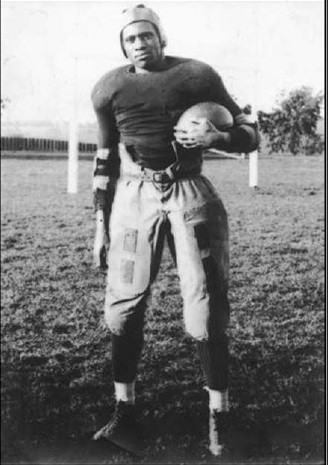

Paul is playing football with older brother Reeve, and Beaty's rich creations fill the brothers' in. 'Clasp the ball to your chest and bend your knees. Tackle.' Robeson among his many talents was a football star.

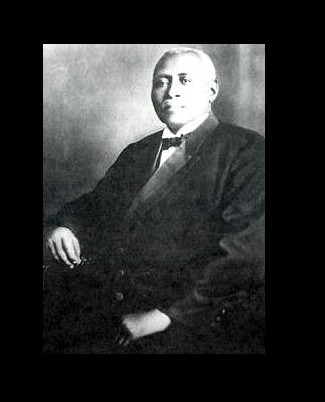

His father William, a runaway slave, brings him into the home to read the Iliad and the Odyssey together. We do not know that William Robeson studied at Lincoln, a college founded by my family before the Civil War began. When black students who had either run away or been freed were rejected out of hand by Princeton or when a local Pennsylania college quickly demoted one student to porter, what was then called Ashmun was created. A rich catalogue of courses was offered: classics, history, philosophy and mathematics. William flourished there.

William would become a minister. Paul was the youngest of his five children. Education was crucial to the family. Paul graduated Phi Beta Kappa and as valedictorian of his class at Rutgers. He was also a star football player. He then went to Columbia Law School which he financed by playing professional football.

The stings of racism hit him hard as he entered the legal profession. One evening he sang in the home of critic and photographer Carl Van Vechten. Eslanda Cardoza Goode heard him. She told him to give up the law and become a performer: He was a natural.

In another of the delicious two-handers Beaty creates, turning one character into another and back with seeming ease, Essie teases Paul away from law and onto the stage. As Essie pin-pricks his career, they marry.

Beaty's re-creation of a man and his life is monumental but deeply personal. Not only does Beaty play Robeson from five to 77, but he inhabits 40 other roles. Harry Truman is Harry Truman, and kicks Robeson out of his office. We do not meet Stalin although Robeson did. Essie as depicted by Beaty is a star turn.

You begin to anticipate Essie as Beaty lifts his arm, drops his wrist, raises his voice and prances. What a woman. She was head histological chemist of Surgical Pathology at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital and gave it up to manage Paul's career. Robeson says that he never intended to become an actor but went on stage to get Essie to quit pestering him. She never does. Yet you see her contribution to his backbone and his vision.

Other women and other interests would cool their relationship over time, but they were always bound. She was as bright as he was. And Beaty is enchanting and wicked and touching when he plays both parts of their dialogue. Clearly Robeson's wife and his father helped make his towering career possible.

Interwoven through the evening are many of Robeson's most famous performances. Beaty is more than up to music. From spirituals which were such a vital part of American black culture to rabble rousing work songs and rah-rah songs like Ballad for Americans to raise money for American war bonds, the dedication of a man rises up.

Moises Kaufman directs with a bold humor and wit, always leaving the man at the center.

At the center of Robeson's soul sat a phrase which he probably did not know is carved on the entrance to FDR's high school, 'Cui servire regnare est' (whose service is perfect freedom) as his own modus vivendi. Robeson speaks of having been given gifts and using them on behalf of others. He used his celebrated voice as a civil rights leader, focusing on lynching, as a labor leader and as a man who looked hard to the 3 %. Class and racial issues became one for him.

The tendency of our country to freeze and cry "Red" after the Second World War left Robeson a wounded man at the end of his life. But what a glorious life it was. Beaty and the Tectonic team capture it in the round. A moving and mesmerizing evening at BAM.