Chunky Moves Mass MoCA

Connected with Strings Attached

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 25, 2012

Connected

Chunky Move

Directed and Choreographed by Gideon Obarzanek

Sculpture by Reuben Margolin

Composers Oren Ambarchi and Robin Fox

Lighting Designer Benjamin Cisterne; Costume Designer, Anna Cordingley; Executive Producer, Catherine Jones; Stage Manager, Melanie Stanton; Sound Operator, Nick Roux; Master Electrician, Marko Respondek

Performers: Stephanie Lake, Ross McCormack, Gabrielle Nankivell, Marnie Polomares, Joseph Simons; Gallery Attendant Vocal Recordings: Geraldine Cook, Brigid Gallacher, Brian Lipson, Mike McLeish, Robert Menzies, Alison Whyte

Mass MoCA, March 24 and March 25, 2012

In Partnership with Jacob’s Pillow Dance

Supported in part by the Irene Hunter Fund

Introducing the Australian dance and multi media company Chunky Move last night at Mass MoCA the co-presenters, Joe Thompson, director of the museum, and Ella Baff, the artistic director of Jacob’s Pillow Dance, noted that the arts organizations have now collaborated for thirteen years.

In presenting the work of the diverse and inventive choreographer and company founder, Gideon Obarzanek, arguably, never more appropriately.

The complex single work of the evening Connected that drew a near to capacity audience conflates his interest in dance and fine arts.

Baff noted that Pillow has presented the company on several occasions. But this is the last time under the direction of Obarzanek. As of July 1, 2012, Anouk van Dijk, a choreographer based in the Netherlands, will commence her role as Chunky Move’s new CEO and Artistic Director.

Obarzanek founded the company in 1995. A chance meeting with Australian actress Cate Blanchett led to a position as an associate artist with the Sydney Theatre Company. As he told the LA Times, at 45-years-of age "After 16 years of running my own company, I want to put my energy into the works themselves and not so much into an organization. I'm lucky that I'm in a position now where I can walk away from Chunky Move knowing it will do well without me."

With perhaps TMI Baff informed us that one of the elements of the inventive piece entailed literally building the set during the performance. That removed a key element of surprise and wonder. It was information that might have been explored during a dialogue between Baff and Obarzanek following the performance.

After introductions there was a very long pause. It was sustained with such suspense that you wondered if it were a part of the work. That encouraged contemplating the stage dominated by a very large, horizontal object. On one end was a large wheel like device from which were threaded and extended a number or thin ropes or strings. These splayed out at an ascending angle and then dropped down forming a large grid, several feet square, at a uniform height. The individual strands all ended with a cap like device.

What proved to be the mechanical apparatus of a kinetic sculpture was designed by the California based artist Reuben Margolin. The artist and choreographer met at the PopTech conference in Camden, Maine in 2009. Pursuing a collaboration proved complicated since they were separated by continents and as Obarzanek commented “Reuben doesn’t like to fly.”

Hmm. That would seem to be a problem.

Initially, Obarzanek worked on movement with the company. He tends not to think of what he does as dance or even that he is primarily interested in dance or dancers as such. He finds dance, oddly, not that interesting and professional dancers even less so. They have a vocabulary of accomplished movements that of themselves, lacking invention and humanity, devolve into being enervating.

Or something like that. I am paraphrasing.

As to how he finds his dancers he surprised the audience by saying that he hates auditions, conducts them rarely, and doesn’t find them very useful. The audition, instead, comes through the process of building a dance. What he looks for in participants is their own instinct for choreography, passion, improvisation and invention. If their collaboration is successful it leads to an invitation to be involved in a new work.

Yes, I know. That sound’s really complicated. But it’s not, really.

It describes a restless, easily bored and distracted, boundlessly curious, inventive, experimental artist. By his own admission it doesn’t always work. He was charmingly and disarmingly frank in commenting that his ideas do not always succeed. There has been a range of audience and critical responses from praise to pans.

Arguably, it clarifies why having founded a successful and critically acclaimed company that tours globally, he would opt to move on. It evokes the sense of a brilliant artist approaching mid career ready to take on new and different challenges. There is always that next mountain to climb.

After that sustained pause a single female dancer burst onto the stage throwing herself about in frenetic, seemingly illogical, patternless, chaotic movement. The sound, music does not seem appropriate, by Oren Ambarchi and Robin Fox, evoked grinding gears evolving into static. It made me think of Ballet Mécanique, 1924, a project by the American composer George Antheil and the filmmaker/artists Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy.

It was an interesting metaphor for Margolin’s sculpture. In previous works Obarzanek commented that he had explored computer and digital elements that are complex to program and often frustrating to work with. There is none of that in Connected which reverts to the Industrial Revolution and the all in plain view mechanics of an aesthetic machine.

Is Obarzanek's Connected to be thought of within "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" the widely influential 1936 essay by German cultural critic Walter Benjamin? Or MoMA's 1934 exhibition Machine Art?

The single gyrating woman was joined by two others and then a male dancer. Later we learned during the discussion that there was a mathematical calculation based on Chaos theory that informed the sequences of movement.

Hey. Who knew.

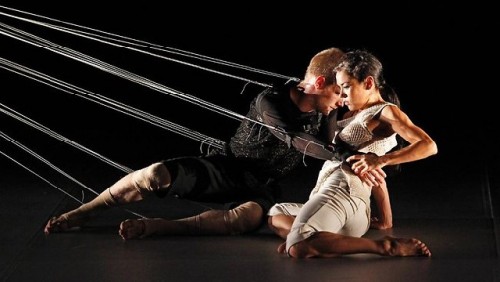

While the mechanized dance continued as a kind of visual distraction we noted that a male dancer, later joined by a woman, was methodically connecting the ends of the suspended threads with flat, broad elements of uniform length. When this was accomplished it resulted in a suspended grid. On the other side of the stage the strings were then attached to the arms and legs of four dancers.

Once connected, through movements, the grid was manipulated to move and flow in a great variety of configurations. Moving back and forth the grid could be raised or lowered. Movements of arms and legs resulted in flowing movements. Critics have evoked the image of a swimming, giant sting ray with its flat, mobile, delta form.

We were utterly fascinated by this sequence of the dance. But there is a limit, which the choreographer discussed, where the novelty and invention must morph and change, adapt to some kind of narrative development and culmination. Surprise and invention are not enough to sustain an aesthetic experience. There is an inevitable sense of ok, I get it, now what.

From four dancers attached to the apparatus there was a reduction to a single male. This led to a pas de deux and complex mechanical romance/ frustrated seduction. For all his striving and reaching out to her, literally, there were strings attached.

In a truly Newtonian sense for every action he made there was an equal and opposite reaction. The device was raised and lowered, fluttered and surrounded her in varying configurations.

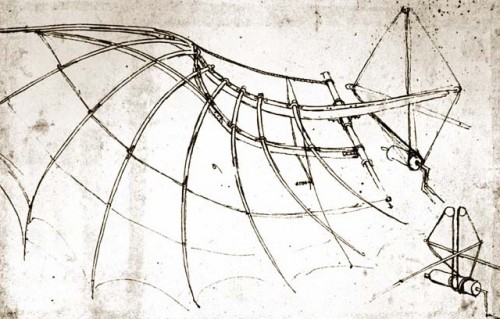

Many aspects of the device reminded me of a Jacquard loom. Puppetry. Or the inventions of DaVinci particularly his plans for a flying machine. With a different sound track Obarzanek’s dance might have been a court entertainment during the Renaissance or the Age of Enlightenment.

As the evening progressed there was a sense of discreet segments and episodes of the dance with a sense of wonder and surprise threading through. But nothing led us to anticipate the final and most startling element.

The five dancers, three women and two men, returned to the stage dressed as museum guards. Margolin’s device assumed the identity of an object in a museum which led to the conjuring of the guards.

The very tall woman spoke.

I was startled. A paradigm of dance is that it is mute.

Ok, perhaps a line or two uttered for shock value.

But soon all of the guards were speaking. Based on actual interviews. The script conveyed a jumble of thoughts on the demands and tedium of the occupation. How to get through those long shifts and its inevitable, frustrating boredom. But, in one distracted moment, a priceless object might be damaged or stolen.

This play within a dance completely distracted us from the Exquisite Corpse which had engagingly preceded it. What to make of such a complete non sequitur other than in the interest and imagination of the chorographer. And how to get back to and conclude with the primary theme of dance?

The guards stripped down to their white shirts over black underwear and bare legs. Awkwardly and disjunctively they resumed a brief dance sequence that found them lying on the floor under the grid.

Applause. No standing O.

During the Q&A I asked Obarzanek about the disruption of the spoken play seemingly violating the norm of dance. In my restless dream last night we pursed the dialogue over beers at a nearby bar. The conversations with the dancers, a figment of my imagination, never happened. It entailed what they will do next under a new artistic director.

His answer, the real actual one, was fascinating. Again it was about his restless resistance in staying put within the confines of dance. It emanates from his fascination with other art forms. He commented that it was the first time that Connected had been performed in a museum setting. It made him wonder what the curators, and in particular, the guards would think.

Perhaps the play within a dance is a signifier that he is now breaching the boundary between the disciplines. In the final work for the dance company he conflated these interests as an experiment and indicator of what may lay ahead.

Wih stunning honesty he commented that there have been varying reactions to the Museum Guards sequence. Many have strongly objected to it and he admits that it may not have been successful. Then, impishly, and all too humanly he said.

“But I like it.”