Ecuador: Part Two

The Amazon Basin

By: Zeren Earls - Mar 26, 2009

A 30-minute flight from Quito over the eastern slopes of the Andes took us to the town of Coca deep in the jungle by the Napo River, Amazon's longest tributary. Along with the spectacular aerial view, changing from snow-capped mountains to an endless green tapestry with the sinuous river running through it, the temperature rose to 86F. Huge clouds drifted by, ready to dump their moisture onto the rainforest. In Coca, an open-sided minibus with a luggage rack on top transported us to the boat dock, where we were fitted for jungle boots and donned life jackets for our motorized dugout canoe ride to the Yarina lodge, our home for the next three nights.

During the one-hour trip, our captain skillfully steered the canoe downriver, dodging drift wood in the murky waters, while Roberto, our naturalist guide, peeled his eyes close to the shore to spot wildlife. Mangroves crowded the river's edge, tall trees stretched toward the sun, and vines drooped into the water, multiplying in its mirrored surface. Shrill sounds of woolly monkeys filled the air, while stunning blue butterflies fluttered by. Parting ways from other boats, we turned to an inner canal to get to our lodge. The staff was waiting at the dock with hot washcloths and lemonade for a much needed refresher.

The lodge manager briefed us about basic rules on the premises: There was no electricity; a generator operated from 6am to noon and again from 6 to 10 pm. Battery-operated power was available for emergency purposes. We were to refill our water bottles from a supply of filtered water in the bar. All our valuables, bagged and identified with our room numbers, would be kept in the central safe. Following lunch, we would rest until 4 pm, since it was "hot enough to fry an egg outside" before then. We were asked not to enter our cabins with boots. Lunch was potato soup, beef with choice of steamed carrots, squash and rice, followed by custard for dessert.

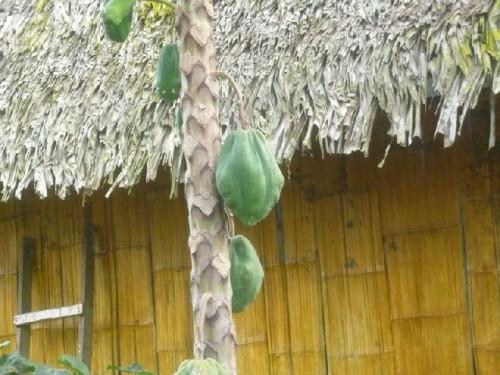

Our cabins were thatched roof huts on stilts constructed to withstand the extremes of the jungle climate; each had a porch with a hammock stretched diagonally across in addition to the multiple hammocks in the main lodge. Despite the heat and humidity, long-sleeved shirt, long pants, sun hat and rubber boots were my usual jungle wear for the nature walks. Additionally, I wore a light-weight travel vest with multiple pockets to carry sunglasses, camera, spare battery, insect spray and sun screen. A water bottle bag with a shoulder strap kept my hands free to take pictures. During our nature walks, Roberto carried his telescope and tripod for close-up appreciation of wildlife. In addition to Roberto, two natives accompanied us to help spot wildlife.

To experience the rainforest through the eyes of a passionate naturalist was a treat in understanding the Amazon Basin and its unique eco system. Roberto spotted birds, tree frogs, lizards, squirrel monkeys, flying turkeys on tree tops and brought them within reach with his telescope. He took photographs by strategically placing my camera lens against that of the scope, thus enhancing the zoom capacity. With a belief in "hearing is the way to seeing", he followed high pitched sounds to spot toucans along with a red capped cardinal, a blue striated heron and the white potoo.

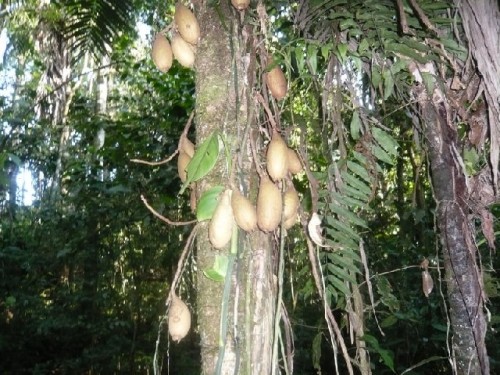

There are 400,000 of species of tree in the rainforest. Competition among the plants and trees for rain and sunlight is fierce. Only about 5% of sunlight penetrates the jungle canopy; therefore, the rain on the ground does not evaporate. Thus, two very different habitats for plants and animals coexist in a compact space; trees on the ground do not like the clay soil and instead spread surface roots on the forest floor. Conditions at the very top of the forest, where cacti thrive, are desert-like.

The following morning we observed the forest canopy from above by climbing one-hundred feet up a giant tree tower enclosed by scaffolding, which supported a stairway. To minimize the weight on the stairway, we climbed in two groups of eight. While one group ascended, the other watched our indigenous guides weave a basket out of palm leaves. Flowers and plants in the upper ecosystem loved sunshine and never descended to the forest floor. No sting bees, which looked like tiny black flies, swarmed around us, attracted to the salt in our sweat. Once we got down to the ground level, there was no sign of these flies despite the increased sweat!

On our way back, we spotted birds' eggs buried in the forest floor. Unfortunately, their camouflage had not kept predators away; the eggs had been vandalized. Among the variety of mushrooms, the one-day mushroom was unique. Called "the penis of the devil" by the natives because of its shape, this mushroom begins tilting as the day wears on, and is flat on the ground by nighttime. Other sightings included colonized spiders, leafcutter ants and a wild juvenile tapir feeding on fruit leaves, using its trunk-like nose to grab them. Baby tapirs are born with a striped pattern that helps camouflage them; the stripes fade away as they mature. Identifying a variety of palms, used in making hats and baskets and vegetable ivory, used for buttons and decorative objects, completed our morning walk.

After the siesta our motorized canoe took us to a wild animal sanctuary, where we saw large land turtles and watched birds over the lagoon from a lookout balcony. Toward evening, we paddled in four small boats around the lagoons, searching for caimans. They nest near tree roots and pile up leaves for camouflage to protect their young. Shining a flashlight into the reeds, we spotted two lying very still in the water; their red eyes stared back, reflections from their retinas. Although Roberto assured us that they were harmless, the vicious-looking reptiles discouraged me from flashing my camera on them. We paddled back through shimmering waters lit by glow worms as tree frogs serenaded us.

The visit to an Amazon village school was a memorable experience. We arrived at the shore by canoe and walked through the jungle. On the way we learned about heliconia, with red flowers, and balsa trees, bearing white ones resembling little balls of cotton. We saw orange tarmarin monkeys at a distance and watched butterflies mate close by. Trees marked with orange ribbons identified areas of seismological exploration for oil. The discovery of oil in the late 1960s has since transformed the indigenous communities from quiet jungle dwellers into tough land negotiators with oil companies, which also build roads. Ecuador's oil wealth is responsible for much of the restoration of its colonial cities.

The children were in the school yard for the daily flag ceremony when we arrived. Eleven students, ages 6-13, including a four-year-old visitor, filled the one room school house. The teacher, serving his compulsory two-year duty to serve in a rural area after graduation, had a mother assistant responsible for breakfast. In turn, six mothers bring breakfast to school every morning at 7 and stay on to assist the teacher, who commutes from Coca on his motorcycle. The class meets from 8-10:30 and again from 11-12:30 following recess. The children introduced themselves as customary in Ecuador, by mentioning their given name, followed by the last name of both the father and the mother. They sang for us and showed their books, provided by the government to standardize education. In response to our query about needs, we received a list topped with notebooks, magic markers and toothbrushes, which the group bought for them.

Afterwards, we visited an indigenous family from the San Carlos community. The young family with two daughters, one of whom we had met in school, offered us a drink made of peeled and smoked casaba root left to ferment on its own. We snacked on skewered chunks of gourd, roasted and salted, delicious. This family grew everything they ate and fished in the river, which also served them for bathing. They made handicrafts, such as gourds etched with local imagery, necklaces made of seeds and wooden combs.

For the next cultural discovery we paddled to the local yachak's hut to witness a healing ceremony. Wearing a grass skirt and red markings on his face, the 37-year-old healer told about his training since he was two. His knowledge of medicinal herbs came from his mother and of healing rituals from his father; he was the third-generation healer and in turn was training his own son. He spoke of the healing process not as a way of getting rid of bad energy, but as a means of balancing good and bad energy. To demonstrate his point he asked for volunteers, who included my sister. With fans made of palm leaves, one in each hand, he began fanning with increasing speed around Fulya, seated with her eyes closed and palms up, ready to receive good energy. Then the healer smoked a cigar wrapped in a banana leaf, blowing the smoke over her head several times after inhaling it. He finished by fanning her again as he whistled. All relaxed, Fulya opened her eyes.

A cooking demonstration followed: We watched as a small piranha was chopped into bite- size pieces, including the head and bones, and marinated in a mixture of chopped red onion, garlic, cumin, salt and pepper and hot sauce made of peppers and tree tomatoes. Then it was wrapped in banana leaves, tied tightly with vines and cooked over hot coals. We enjoyed it with steamed maniac root, plantains and finger bananas, kept in their skin, and wrapped in leaves for cooking. Another delicacy was grubs, cleaned and skewered for roasting or steaming. Grubs are found on palm leaves, are therefore full of palm oil, which drips away during roasting, and are quite delicious cooked in this way.

In the morning we woke up to a tarantula on the ceiling. Fulya, petrified that it might jump on her, asked me to wait till she dressed and left the room as I reached my camera. In the meantime, the tarantula disappeared, much to my disappointment for the missed photo opportunity. After a breakfast of guava juice, scrambled eggs and pancakes, we had a wonderful canoe ride down the lagoon, transferring to the motorized canoe to get to Coca for our flight back to Quito to begin our next adventure, the Galapagos Islands.