Architect Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe At 126

A Modernism Founder Reconsidered

By: Mark Favermann - Mar 29, 2012

A few days ago, March 27, was Mies van der Rohe's birthday. The German-American architect would have been 126. He died at a fiesty but painfully arthritic 85 (1886-1969). His fame or at times notariety was so great that he was and is referred to as just Mies. Along with Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer and a few others, he is considered a master of Modernism.

Using modern materials and methods like stainless steel, plate glass, simple elegant connections, etc., Mies strived for an architecture with a minimal framework of structure balanced against free-flowing open space. There was a studied open geometry to all of his work.

He is well-known for his architectural aphorisms. Calling his buildings "skin and bones" architecture, he viewed his design process as a rational approach that guided a creative yet simple, elegant and highly functional architecture.

Mies is credited with saying "less is more" and "God is in the details." These sayings added to his reputation as an architectural leader.

At the end of his career, he was also scorned if not belittled for his ideas and projects. Contemporary critics and reporters often vilified his minimalist work referring to it as soulless. His high rises, often copied by less talented designers, were grouped together as sterile Kleenex Box structures. These unadorned megabuildings underscored the notion of detached big business and unfeeling corporate America.

Mies was probably very depressed and felt terribly misunderstood at the end. This was not at all what his architectural philosophy or design aesthetic intentions were.

Architectural reaction came in the form of Post Modernism. Initially this was advanced by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown who once stated that "Less was a Bore." Later this idea was further popularized by the writer Tom Wolfe in his culturally confused screed From Bauhaus to Our House (1981).

Wolfe's reactionary attack on modern architecture stated that radical modernism imported from Germany had reduced American building to 20th Century impersonal frigidity. It was a dubious argument then and is in many ways just ridiculous now.

Postmodernism began as a response to the unadorned blandness and Utopianism of the Modern movement. Modernism was focused on the pursuit of a perceived ideal of perfection, and attempted harmony of form and function while dismissing ornamentation. Postmodern architecture including works by Michael Graves and Venturi Brown rejected the concepts of a pure form and/or perfect detail. Instead, Post Modern designs drew from a variety of methods, materials, forms and colors available to architects.

Postmodernists openly challenged Modernism as rigidl and totalitarian. It instead championed the ideas of personal preferences and variety over objective, ultimate truths or principles. After a few years, Post Modernism was faulted for its simplistic stage set qualities that used ornamentation as an architectually personal visual language of adornment that was added to simple forms. The criticism was focused upon stagey architectural forms, personal yet rather arbitrary symbolism and decorative but vacuous visual language.

In the following decades, with more malleable and flexible materials and construction techniques, contemporary architecture has literally built upon the elegance of Modernist principles often using building form and materials in place of traditional historical ornamentation.

With that said, in recent years, Mies van der Rohe's work has been reconsidered, and the architect has been reputationally revived.

Mies began his career by first working with in his father's stone-carving shop. Then he went to work at several local design firms before moving to Berlin. There he joined the interior design firm of Bruno Paul.

His true architectural career began as an apprentice at the studio of the major and visionary German designer of the early 20th Century, Peter Behrens. He was there from 1908 to 1912. Since the firm designed something of everything including logos, furniture, appliances and architecture, the experience at Behrens studio must have been a major influence on Mies.

Here he was exposed to the most current design theories, progressive ideas on German culture and new construction methods. Imagine his conversations while he was working with two other future stars Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier who were apprentices at the same time!

Mies's major project during that time was to serve as construction manager of the new German Empire Embassy in Saint Petersburg, Russia for Behrens.

Mies, like many of his post WWI contemporaries, sought to establish a new architectural style that represented modernity. This was in careful opposition to Classical, Gothic and Baroque styles and their often overdone 19th and early 20th Century pastiches. Along with other prominent contemporaries, he created an influential 20th Century architectural style with extreme, even for the times austere visual clarity and simplicity.

His talent was early on recognized, and he soon began receiving commissions. This was despite his lack of a formal college level education. He was virtually self-taught. Physically imposing, deliberative, and very often reticent, the stonecutter's son Ludwig Mies renamed himself van der Rohe. Thus, he transformed himself into an appropriate architect working for Berlin's elite.

His career began by designing upper class homes. His work was part of the movement that sought a return to the purity of early 19th century Germanic domestic residential styles. He admired the broad proportions, regularity of rhythmic elements and attention to the relationship of the built environment to nature of the major nineteenth century Prussian Neo-Classical architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Schinkel designed much of 19th century Berlin.

Aesthetically, Mies rejected the eclectic and cluttered neoclassical styles that were common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He saw them as anti-modern. His earliest houses, though neoclassical, were simpler and less complicated than those done by most other residential designers.

Following WWI, Mies joined with his avant-garde peers in search of a new style that would be suitable for the modern industrial age. Traditional styles had been under attack by progressive theorists since the mid-19th century for the contradictions of hiding modern construction technology under a superficial facade of ornamental hodgepodges of traditional styles.

These historical styles after World War I represented the failure of the old world order of imperial European leadership. These architecturally symbolized a discredited social and political system. Progressive thinkers rejected the past in favor of a new architectural design process. This was to be guided by rational problem-solving and an exterior expression of modern materials and structures.

During the early 1920s, Mies began to develop visionary mostly unbuilt projects. These concepts brought him positive recognition and fame. Thus, he became an architect thought to be capable of giving form to the emerging modern environment.

Mies's design thinking was influenced by many design and art movements of his day. He selectively adopted and incorporated contemporary ideas from the aesthetic credos of Russian Constructivim, Dutch De Stijl (primarily articulated by the work of Gerrit Rietveld) and architect/designer Adolf Loos.

Like many other European architects, he admired the work of American architects and engineers, especially the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright's Wasmuth Portfolio (1910) was published and exhibited in Berlin. Peter Behrens bought one of the portfolios. Work was stopped at the Behrens studio for a day for the staff including Mies, Le Corbusier and Gropius to review the prints.

Mies was enchanted with the free-flowing spaces of inter-connected rooms of the open floor plans of Wright's Priairie Style. He also appreciated the beauty in functional construction of American engineering structures.

Abandoning ornamentation altogether, in 1921 Mies made a dramatic modernist debut with his brilliant competition proposal for the Friedrichstrase Skyscraper, a visually revolutionary faceted all-glass structure. This was followed by a taller curvilinear version, the Glass Skyscraper, in 1922. Many of today's most geometric structures are in this tradition.

This visionary or paper architecture led to Mies being selected to create the German Pavilion for the Barcelona International Exposition in 1929. This elegant and pure geometric temporary structure (often referred to as the Barcelona Pavilion) was torn down in 1930.

Even though impermanent, it was so seminal a design that it was considered one the major pieces of Modernist architecture. Its layout and design have been studied at architecture schools for decades. In 1986, Spanish architects with government and foundation funding carefully reconstructed it on its original site.

Another masterwork by Mies is the elegant Villa Tugendhat in Brno, Czech Republic completed in 1930 for a wealthy Jewish industrialist Fritz Tugendhat and his family. In 1938, they were forced to flee to Switzerland. The house was used by the Gestapo during WWII and badly abused. After the war, the Soviets actually used part of the structure for stables.

It eventially was partially restored by the Czech government. Tugendhat descendents sued to have the house properly refurbished. After years of deterioration, Villa Tugendhat was recently restored (at a cost of $8 million) to its original condition and was opened in February 2012 for public tours.

Both the German Pavilion and the Villa Tugendhat are Mies's European masterworks. They both are considered Modernist icons and are each UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Mies did not limit himself to just architecture but also to how his spaces were furnished. Perhaps one of his most famous creations was his Barcelona chair and ottoman that he designed for the German Pavilion in 1929. The chair was to be a seat for the king and queen of Spain. Today, he would be shocked or as the English say gobsmacked by the ubiquitousness of the expensive chair in corporate lobbies and upper middle class homes. Badly made cheaper knockoffs would certainly insult him today.

In the early 1930s, Mies served as the last Director of the Bauhaus, then in its last gasps. After 1933 when Hitler rose to power, Nazi political pressure forced Mies to close the government-financed school. He built very little in those years. His only American commission during that period was for then architecture critic and curator Philip Johnson, a New York City apartment.

Though there is a murky period of him perhaps trying to gain favor with the Nazi regime, ultimately the Nazis rejected Mies' style as not "German" in character. Reluctantly he left Germany in 1937 for the US. Early on, he was given a residential commission in Wyoming. He was also asked to head the department of architecture of the newly established Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) located in Chicago. There he introduced a new kind of architectural and design education and philosophy.

Throughout the 1940s, Mies was an educator but was also allowed to master plan and design new campus buildings for IIT. These included Alumni Hall, the Chapel, and Crown Hall, the home of IIT's School of Architecture. Crown Hall is widely regarded as among Mies's finest work, the definition of Miesian architecture.

Soon after WWII, commissions started to come his way. His early projects at the IIT campus, and for Chicago developer Herb Greenwald, established his mature architectural style. This style became an preferred aesthetic of building for American cultural and educational institutions, developers, public agencies, and large corporations.

Significant projects in the U.S. include several in and around Chicago. The residential towers of 860-880 Lake Shore Drive, the Chicago Federal Center complex, the Farnsworth House, the various ITT campus buildings--especially Crown Hall and New York's Seagram's Building were iconic structures that became prototypes for his other projects.

Between 1946 and 1951, Mies designed and built a weekend retreat outside Chicago for an independent professional woman, Dr. Edith Farnsworth. The Farnsworth House interpreted the relationship between people, shelter, and nature. This residential masterpiece demonstrated that exposed industrial steel and glass were materials capable of creating architecture of great aesthetic and emotional impact.

Farnsworth House is an elegant glass pavilion raised six feet above a floodplain next to the Fox River and surrounded by forest and rural prairies. Here less is certainly more.

Controversially Mies designed a series of four middle income highrise apartment buildings for developer Herb Greenwald on Chicago's Lakefront. The first two were 860-880 Lake Shore Drive (1949-1951). These were followed by 900–910 Lake Shore Drive. The steel and glass towers were radical departures from the typical traditional residential brick or stucco apartment buildings of that time.

The Seagram Building in New York City (1958) is considered the best of modernist highrise design. Mies worked with the daughter of the client, Phyllis Bronfman Lambert (who became a major patron of architecture in her own right) on the now iconic structure. Architect Philip Johnson designed the interior of the Four Seasons Restaurant there. The Seagram Building quickly became a symbol of American corporate power.

Setting a standard for future developments, the architect set the tower back from the propertyline to create a plaza with a fountain. Future Mies projects built on what he created at the Seagram Building.

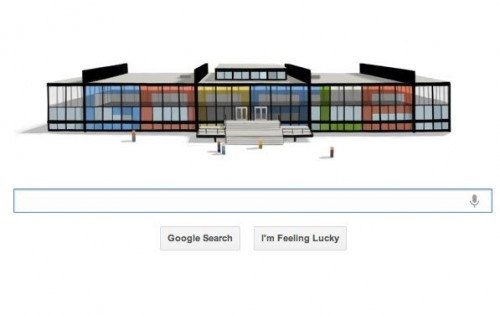

Google, the mighty internet search engine, celebrated the 126th birthday of Mies van der Rohe on March 27, 2012 by incorporating a Miesian building with their logo. Here the Miesian legacy positively meets popular culture. This demonstrates that his aesthetic and philosophy are once again mainstream and positively recognized.

A few years ago, Robert Venturi admitted that he regretted saying that "less is a bore." He acknowledged a debt of all architects and designers to the vision, design and craft of Mies van der Rohe.