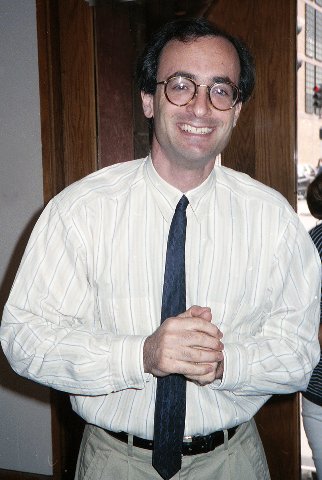

MFA Director Matthew Teitelbaum

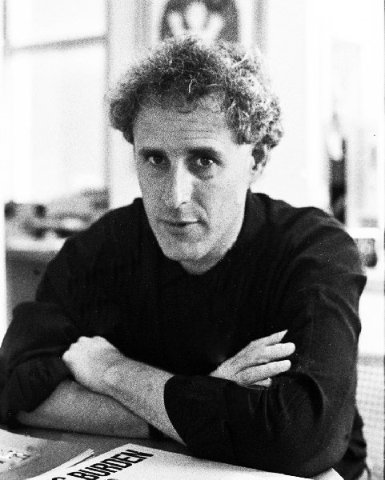

A 1993 Interview with the Acting Director of the ICA

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 29, 2020

In 2015 Matthew Teitelbaum (born February 13, 1956) was appointed the Ann and Graham Gund Director of the Museum of Fine Arts. Previously he was the Michael and Sonja Koerner Director and CEO of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. He is the 11th director of the MFA.

A native of Toronto he holds a bachelor of arts with honors in Canadian history from Carleton University, a master of philosophy in modern European painting and sculpture from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, and an honorary Doctor of Laws from Queen’s University.

Among the publications Teitelbaum has authored and edited are Giuseppe Penone: The Hidden Life Within (Black Dog, 2013); Paterson Ewen (Douglas & McIntyre, 1996); and Montage and Modern Life: 1919-1942 (MIT Press, 1992).

His career as a curator started with the Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon; and the London Regional Art Gallery in London, Ontario. He then joined the Institute of Contemporary Art. During a two-year interval between the departure of David Ross and the appointment of Milena Kalinovska he was the acting director of the ICA.

The MFA among America’s major encyclopedic museums is regarded as having missed the boat on modern and contemporary art. In the 1950s, when Thomas Messer was director of the ICA, there was a plan for it to merge with the MFA as a department. That was nixed when Perry T. Rathbone became director. Modern and contemporary programming and acquisitions have been hit and miss since then.

There is hope for change as Teitelbaum is the first MFA director for whom modern and contemporary art is his field. In the past five years there has been an impact and hope for further changes. Accusations of racism have rattled the museum and his administration. Now the museum is closed because of the pandemic.

This interview occurred in July, 1993 as he prepared to leave for a new position at the Art Gallery of Ontario. An overview of time at the ICA is uniquely relevant because of his return to Boston in 2015. In particular, this exchange provides insights for his curatorial strategies. His vision entails involvement with new work filtered through art history, modernism and theory. We also sat with him in 2019.

Charles Giuliano Will we ever see a fair and objective discussion of the work of Robert Mapplethorpe? Because of the related social and political issues and attempts at suppression and censorship the norm of objective critical thinking has been shut down. Reading recent reviews of the Venice Biennale by Robert Hughes and Michael Kimmelman they don’t give information. There is little discussion of what they saw and evaluated. Their reports wave flags as they deliver polemics. Looking at the current state of arts journalism we don’t see much critical thinking. Shows are endorsed or not but there is little discussion of the work itself. Critics appear to be voting rather than reviewing.

Matthew Teitelbaum In part what you are saying is that there is not a lot of independent thinking going on and I think that’s true. You’re also saying, and I think it’s very true, that truth is equated with the power of speech. The two aren’t necessarily connected. I’m thinking of the work of Hans Haacke in the Venice Biennale. It’s a piece that works in exactly the terms you are talking about in relationship to “Corporal Politics.” When you walk into the piece, there’s an image of it in the Robert Hughes article, you have no option but to say, ‘this is a great piece.’

|

There is no ambiguity. There is no internal contradiction which much great art has. As you say, you cannot be critical of the piece and hold your position on the left. You can’t be critical of the Haacke piece and maintain credibility by saying that you support his other work. You can’t say that this is a problematic piece but, on the other hand, I really believe in Alan Sekula’s work. You’re all in or all out. And I think that’s a problem. The Haacke piece was strong and powerful but, in spite of itself, because it only allowed a single response.

In this climate, and at this moment, I would like to think of the (ICA’s) Malcom X and cross dressing (Dress Codes) as having complexities and contradictions. There isn’t a single position that you can hold in relationship to these exhibitions. That’s part of their strength. It’s not in that sense didactic. We can provide viewers with a lot to read. We don’t make a judgement about whether this art does or does not stand on its own. But we provide a context in which you might more fully understand it.

It’s not, as you say, that we start with point A and that by the end of the exhibition lead you to point B. I do not believe we did that with the Dress Codes show and I don’t believe we did that with the Malcom X show. We do not start with when he was a child and then go through when he rejected The Nation of Islam. We do not say, accept Malcom X as a great orator. We present him with all of his complexities and contradictions. We are trying to find a way for viewers to see different relations to that figure. This, to me, is different from what you are describing regarding the potential tyranny of political correctness. I think it’s your responsibility as a critic to keep saying the things you are saying about the quality of works of art.

CG That creates an adversarial relationship with curators.

MT It’s your responsibility because I think in those comments people will have a chance to respond. To reflect and, as a curator, my judgement changes. I always remember the context in which those judgements were made. I think that Cathy Opie made an important statement and in the context of Dress Codes it was important and powerful. (Photographs of women as drag kings.) There’s very little room to create the context in which it’s seen. Most work depends on the context in which you see it. I’m interested in that problematic and that’s why I’m interested in the ICA.

CG The Nan Goldin pieces (in Dress Codes) could be seen anywhere. The work has been widely shown. They don’t need that show to create context. They don’t need the Whitney Biennial. Her work just needs a wall to hang on.

MT I agree.

CG There is a level or work that achieves ubiquitous celebrity and critical acceptance. For example, provocative images by Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger. Their work is sufficiently emblematic to stand on its own. They don’t require wall text and explanations beyond labels. They don’t require elaborate programming to be understood. To confront an Arbus is to be drawn into its wonder. In a recent show, Alumni Collect, at Williams College Art Museum, there was the Arbus of an interracial couple in a park with a chimpanzee. You asked how she would find such an image? Her images happened as chance encounters when she went around in public with her camera. We are intrigued by her way at looking at and discovering things. The image is now some twenty five years old but retains its impact.

MT What I’m driven by is where does art meet its public? My father was a painter. I grew up with wet oil paintings in my house. The act of making art was a part of my everyday life. I’m a part of that desire to make something. But I’m not an artist and I wasn’t then either. I was somebody who received the art. Having been a student I have dealt with how I have received it. Ultimately, it’s been filtered through me. What drives me is not evangelical but nonetheless there is a drive of find ways to make art meaningful in the day-to-day lives of people. I walk into the homes of friends and am appalled by what people settle for as enrichment of their everyday lives. In terms of what they hang on their walls, regarding the way in which they are prepared to be involved with visual images that surround them.

CG That’s something that bothers me. Through recordings we have access to the full range of music. I can afford to listen to any music that interests me. For art I am limited to galleries and museums. That comments on the elitism of the fine arts regarding the general public as consumers and appreciators. In galleries we have free access to view work but only the wealthy can own it. Once a work is acquired it is removed from public view.

That impacts the ICA in terms of audience. It takes an annual budget of $1.5 million to deliver attendance of some 75,000 visitors. For the city of Boston annual ICA attendance is equivalent to one or two Red Sox games.

MT It’s a bit more than that. More like two and half Red Sox games. But you’re right. But this is my point. Is it the failure of the ICA in terms of what it presents? Or is it the failure of the ICA as an institution that engages in some active way? We showed Performing Objects with Rebecca Horn, Bruce Nauman, Peter Campus, Gary Hill, all tremendously effective work. Yet attendance was miserable. I don’t remember the exact numbers. If you try to figure it out overall attendance it was about half of the audience for Dress Codes.

CG What did that show draw?

MT About 17,000 in that range.

CG What was attendance for the Mapplethorpe show?

MT 104,000 which is mind boggling. We could have had more visitors but that was our capacity. My goal, which drives me, is to have the public meet the art and the art to meet its public. It is an effort to find that meeting place. That doesn’t mean that every exhibition I organize has the same goals or the same way of meeting its goals. I certainly believe in all the art we show. It changes its meaning by the context in which it is shown. I wouldn’t want a whole program structured on shows like Dress Codes and Malcolm X. I want those show in context with other exhibitions.

CG Perhaps it was bad planning to have them run back to back. One provocative theme show right after another.

MT Yeah, maybe.

CG You came here from Canada at an early phase of your career. Now you leave having been like a salmon swimming upstream in Boston. Perhaps the difficulty of navigating the art world here makes you better prepared for challenges awaiting you at the Art Gallery of Ontario in your hometown, Toronto. Can you describe what this transition has meant to you? You came at the end of David Ross as director. There was a transition during a search over two years. That would seem to have given you a lot of curatorial independence. You have had a chance to work with Milena Kalinovska.

MT My time here has intensified thinking about two primary issues. One is that institutions, and not just people, have to take risks in what they do. Institutions have to try to do two things. They have to create themselves as models of thinking that the public will reflect on. That sense of risk taking has to imbue the whole institution. One of the great things about the ICA is that it doesn’t have a permanent collection and it can rethink itself. During the time I have been here it has done that a number of times. I have been fortunate to be here during a time of change. I have been involved in a lot of this rethinking. I’ve been able to direct it for a certain period of time and see first-hand how institutions change. If they want to.

The second thing is that it’s a public institution and a public space which, for me, means that it has a public dialogue. It is not a place that is constructed from a private or individual point of view. It has to be constructed in a manner that a public dialogue can take place. The ICA has not one public but many publics.

Since I’ve been here, I’ve developed sophistication in understanding how different publics can be served. It’s the notion of a museum as a space where a variety of things can go on. You can complement an exhibition with ways in which it can be constructed so that it can coexist not just in a pluralistic way but in an interesting one.

I’m incredibly grateful for the various kinds of lives that the ICA has had since I have been here. I wanted David (Joselit) and Elizabeth (Sussman) to work very intensely. I was involved in a very intense relationship with the board during the period between directors.

I have watched as Milena begins to reinvent the ICA. This has happened in a very exciting context. If you think about it. You have a million dollars to create an institution, then, how to do it? It’s an exciting possibility. It’s not a daunting task. It is daunting, however, in terms of changing people’s expectations. While ratcheting in a different direction. It’s not daunting and devastating in the sense that there is a future. It’s a pretty terrific process and has been exciting to watch.

One of Milena’s challenges it to be realistic about expectations and to help people to be realistic about what they expect from the ICA. About what it can deliver and her incredible energy. There are lot of people willing to work with her and she will maximize whatever she can. It’s going to be tough to do the programming that she wants. If anyone can do it then it’s Milena.

Her time frame has to expand in order to do certain things and she’ll make the right decisions because she will be realistic about the resources of the staff. For the moment it is very much touch and go. You can’t change the structure of the institution and expect to produce the same product. Milena understands that. Again, that doesn’t mean that the product can’t be exciting and develop a loyal following. But she has to be clear about the product relative to resources.

CG Do you have a sense of that product under these circumstances?

MT It will be an institution where artists have a clear voice. Collective collaboration projects will be encouraged. Exhibitions will be linked to public programming. They won’t be an add on to satisfy the fifteen people who want to come to a lecture. Programming has to be thought about in a more organic manner as a part of the presentation of the exhibition. I think the ICA will take council from artist and individuals in the community. That doesn’t mean it will exclusively show works from the arts community. Projects, however, will be pitched in terms of their relevance to the community. That approach is quite healthy.

CG That programming was not notable in the prior (Ross) administration.

MT I will say something you are not likely to agree with. What’s not possible at the ICA is because of the institution that David (Ross) and Elizabeth (Sussman) built together. The ICA that Milena reinvents may be vastly different. But it's built on the foundation that David and Elizabeth left. It is an ICA of serious investigation and wide-ranging curiosity. It is an institution of the highest professional standards. Most importantly is a willingness to go in directions it does not fully understand.

Those are all positive elements. It is often that curators make a mistake. I said that in my conversation with Cate McQuaid (Boston Globe). I’ll say it to you slightly differently. When you enter a creative project. Putting together an exhibition is a creative project. You have a set of possibilities open for the longest possible time. There is a judgement about when you have to close them down. Believe me, I have made a mistake by keeping them too open. But, if you start with the question, what is it you want the content to be? What’s the sets of relationships? Then you’re asking a less exciting question than why do I want to do this? Why do I want to have a dynamic relationship with the issues that are being raised?

Why do I want to put Allan Crite’s work from fifty or sixty years ago in the ICA? Answers to questions about why without being locked into the specific questions of what. Then you can open up a full set of possibilities in which the what comes pretty quickly. The problem with much curating is that you come up with the product seamlessly composed in terms of the answer to what. David and Elizabeth had the urge to ask why?

(Allan Rohan Crite, 1910-2007, was an early African American graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. In an interview with Arthur Dion of Gallery NAGA he discussed a long relationship with the artist. An exhibition of the work, curated by Jean Gibran, opened recently at the private St. Botolph Club, which then closed because of the pandemic. Now that Teitelbaum is director of the MFA he has been approached proposing a major Crite exhibition in a manner that Boston Expressionist, Hyman Bloom, was recently presented.)

CG How might we rephrase that? Starting with the what rather than why? Is it the priority between what and why that we are discussing?

MT Right. I think you enter the field of inquiry which consists of a whole set of questions. Why is this important? Why do we have to think about it now? Why do we want to present it to our public?

If you can ask yourself these questions you can create a field of activity in which a whole bunch of things slot in.

We did this with Dress Codes. In the beginning of the project there were a small number of artists we were committed to. Nan Goldin was one of them. From the beginning (Japanese photographer Yasumasa) Morimura was another one. Ron Davilla had two works. One was a painting of an asshole sticking you in the face. The other was a Papal poster of a guy in a little dress. Actually, we started with another artist who didn’t end up in the exhibition. We started with the question why and moved into what.

This might be one of your criticisms of the exhibition. If you leave in the what too long you don’t end up with the works you want. You haven’t focused on what the content is. But, as a methodology, you have left yourself open from the beginning. The exhibition was done in four months. That’s not meant as an apology. It’s a fact.

We had an historical component. We had plans to acknowledge cinema. We planned to include historical forebears. But scrapped all that. We didn’t have enough time or money. That doesn’t mean that we might have done it with the necessary scholarship. I’m not saying we had a perfect thing and that we couldn’t do it. What I’m saying is that a part of our argument was missing. Our thesis was that this is not just a contemporary phenomenon. It came out of a condition that evolves from a set of historical facts. We tried to acknowledge that in the videotape. That was not a part of the exhibition and its construction. (Branka Bogdanov created remarkable video documents of ICA exhibitions.)

CG If you had more time and money what might have been different?

MT We would have done that. But we didn’t because of specific circumstances. That is the problem that starts so rigorously with the question why and, by the time you get to what, you may not have enough time. When you want somehow to ask the question what as quickly as you can. That level of curiosity, which I like to think I have as a curator, and what I believe David and Elizabeth brought to the ICA, allowed us to work together as well as we did.

CG Now that you are leaving town what shape is the ICA in?

MT I feel that there are parts of Boston still opening up for me. There are parts of the city that I don’t know. I truly believe there are some exceptionally intelligent artists of outstanding merit in this community that are doing things.

CG Milena tells me she plans to be here for the next decade. Do you think there is enough to keep her here that long? Is Boston a sufficiently dynamic community to hold its best talent?

MT The ICA has a role that allows us to talk to each other and to reach the public more directly. Not as individuals, but as part of a dialogue, and that will keep Milena here.

CG As a native Bostonian I have accepted having a provincial career. With proximity to highways and airports, however, it’s less relevant where you are from than where you have been, and who you are talking to. Critics and curators become provincial when they don’t travel. There are too many examples of that in our community. One can be both provincial, planting roots and working with the community, as well as involved with global issues.

MT The ICA has that role to play there. You’re talking about access to information and experience that may, or may not, be rooted in Boston. You have access to other experiences where you don’t feel strange or isolated. The ICA plays a role by allowing access to greater information.

David and Elizabeth opened Boston to that new information. They made it accessible to individuals who need and benefit from that.

CG It often felt that a direct connection was lacking. If you include more people in the dialectics, make them part of the process, there will be wider interest and acceptance of programming. It isn’t effective for the ICA to be an elitist laboratory and think tank. That’s a part of why attendance remains marginal.

MT The challenge is to get Boston’s artists involved with what’s presented by the ICA.

Link to 2019 interview with Teitelbaum.