Gerard Malanga at Pierre Menard Gallery

Cambridge Retrospective Evokes Reflection

By: Gerard Malanga and Charles Giuliano - Mar 30, 2010

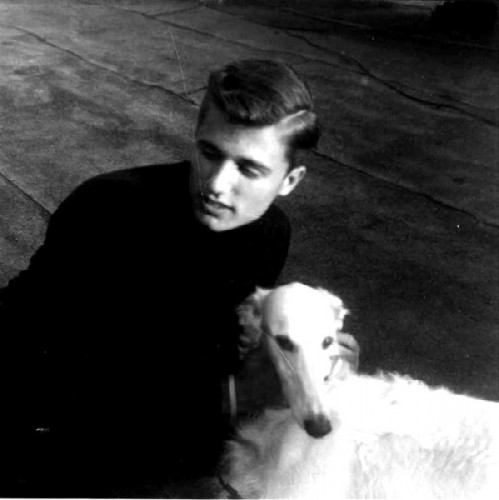

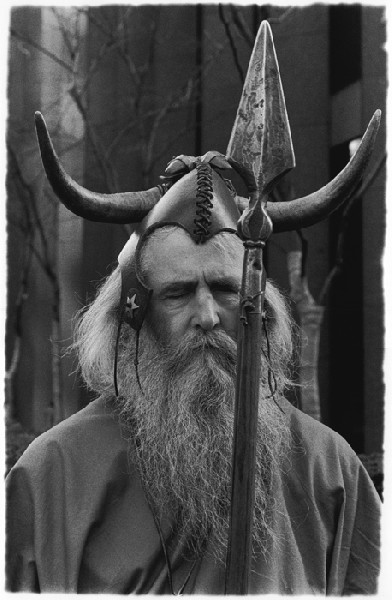

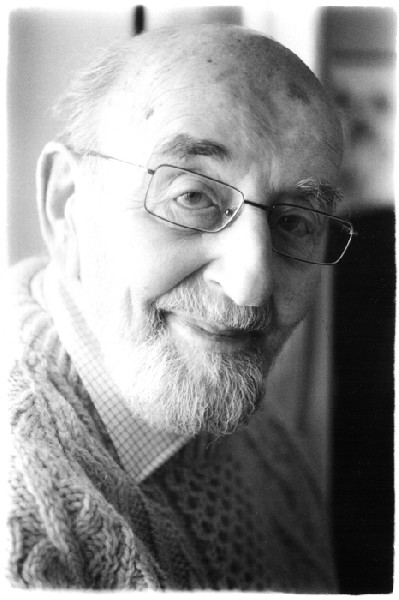

Gerard MalangaSouls

Pierre Menard Gallery

10 Arrow Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

March 12 to April 12, 2010

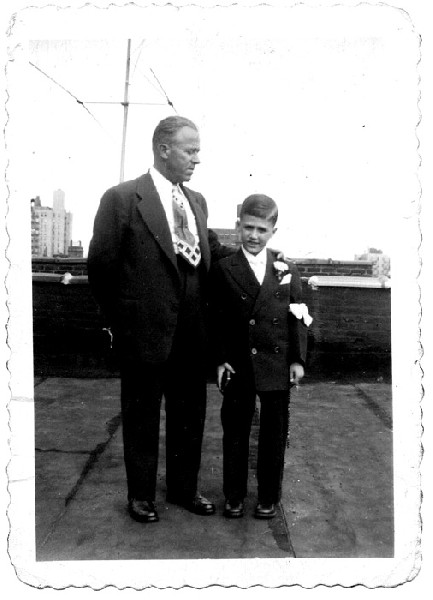

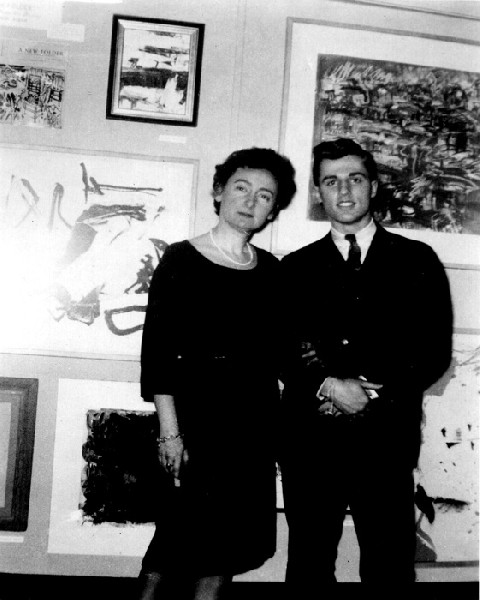

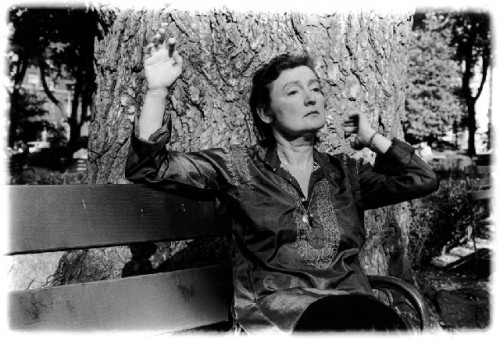

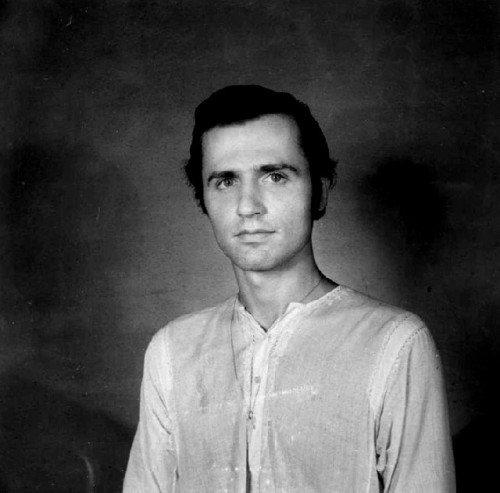

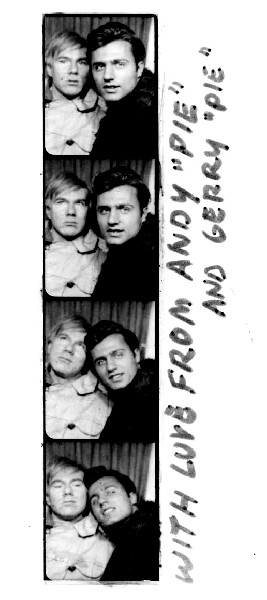

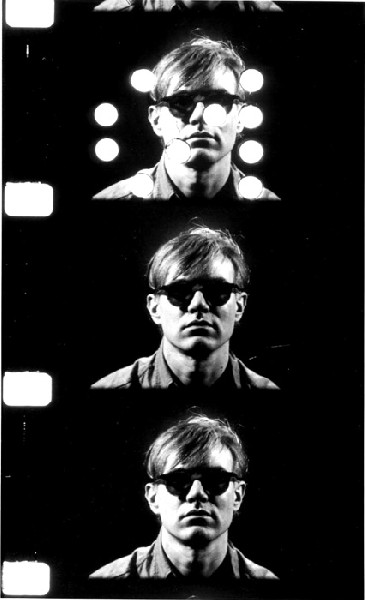

Archives Malanga

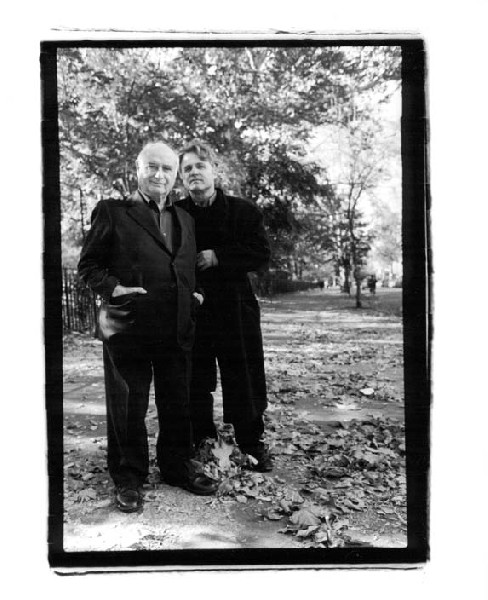

Back in the 1960s I first encountered Gerard Malanga when he performed his Whip Dance with the Velvet Underground as a part of Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Around 1969, the time frame of the earliest images in this exhibition, we met in the Berkshires. Since then we have remained close friends and collaborators.

This interview in three parts was conducted by e mail over several days. Gerard, whom we affectionately call 'The G," referred to it as a "tennis match." I would "serve" a question and after an interval he replied. I compiled these exchanges into a file which he then edited. Between "sets" there were e mails and many phone conversations as the focus and content took shape.

For both of us it was a challenging and enriching experience. Of course Malanga has been interviewed many times usually in the context of his association with Andy Warhol and the Factory. But that was not the focus of our exchange which probed into the poetry and photography; its process and sources. Also the reflections of an Adonis who defied the Gods by not dying young.

This is another of a series of on going projects. When I was the guest editor of an issue of Art New England we created a cover story. At that time The G was living on 14th street. I visited for a weekend, and we tape recorded constantly, even in the cab on the way to Chinatown. He transcribed the tapes and we edited them together. The interview has been included in many subsequent bibliographies.

On another occasion I curated a Jack Kerouac themed show on the Beat Generation for Suffolk University with the Brush Gallery in Lowell during the city's annual Kerouac Festival. Gerard provided a number of his photographs.

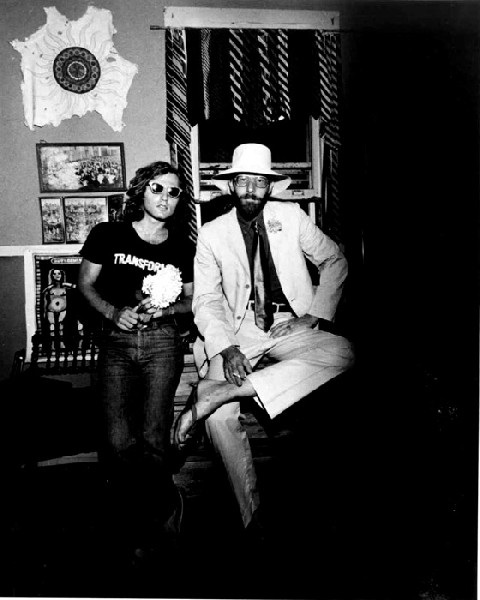

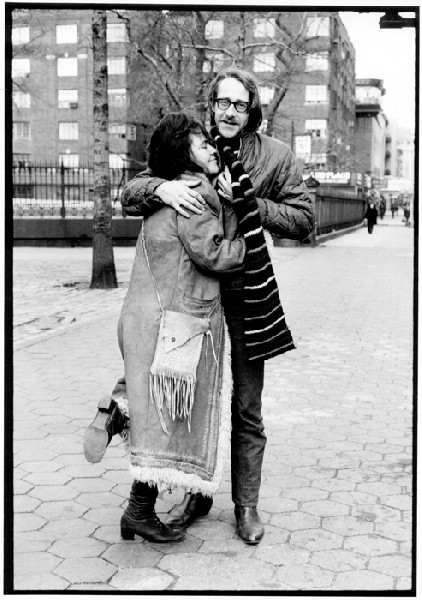

For this project Malanga has dug into his archives to provide a number of rarely seen vintage images. We are also grateful to Menard Gallery for allowing access to a selection of images from the exhibition.

CHARLES GIULIANO: In the current exhibition at Pierre Menard Gallery in Cambridge there are some 100 vintage, black and white images. This is quite an accomplishment for a photographer who has never spent a day in the darkroom or like most of us then moved on to Photoshop. Is that a point of pride with you? Like the fact that at 67 you still don't drive a car? Cabs must be harder to come by now that you don't live in the city.

GERARD MALANGA: I have no opinion one way or the other. It would seem the technology passed me by but that's for someone else to discern. So it's never been an issue of pride and as far as not driving a car is concerned... well, Kerouac didn't know how to drive either. He had Neal Cassady chauffeur him cross-country and every which way. How else could he have written On the Road? He was holding a pen in his hand; not a steering-wheel.

CG The Pierre Menard exhibition has been reviewed by Mark Feeney in the Boston Globe. You mentioned that it is the first time one of your exhibitions has been reviewed. Of course every exhibition has its own unique flavor. Several years ago I showed a number of your images in the Kerouac Beat Tribute.

We had arranged to borrow a number of Ginsberg's inscribed images from Tibor DeNagy Gallery and from Elsa Dorfman who made many Polaroids of Allen. Just before the show he died and they refused to lend. I showed my own Ginsberg and was very grateful to you and Fred McDarrah for your generous loans. I bought two of McDarrah's Kerouac images. I also own a couple of Elsa's.

So what did this Cambridge show mean to you and the significance of that Globe review?

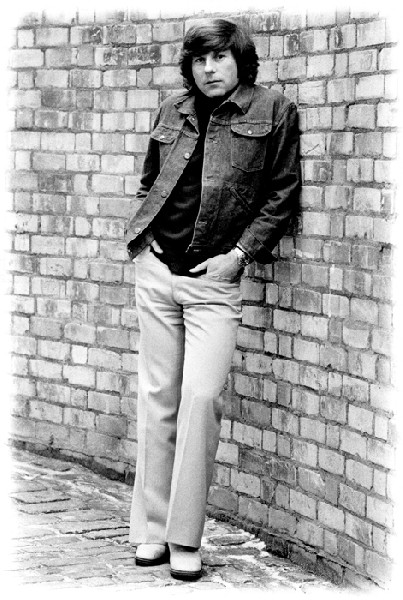

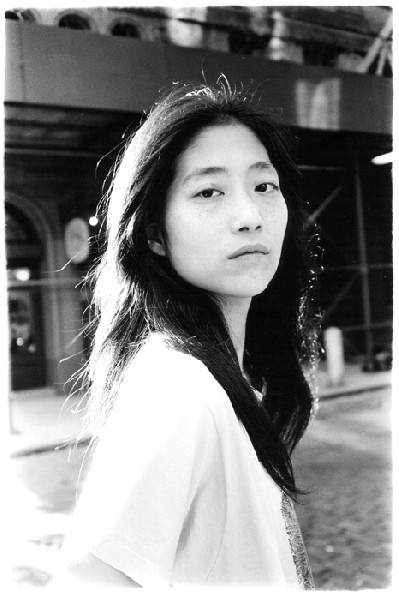

GM: For many years now, whenever I had to go into the files looking for a particular negative and contact sheet, I would invariably come across contact sheets and remark to myself how I should print this or that portrait; and it wasn't a picture of someone famous necessarily. I just felt that I would like to see a show of my work where all these faces, all these people, could be brought together and equally share space and equally be on a par with each other.

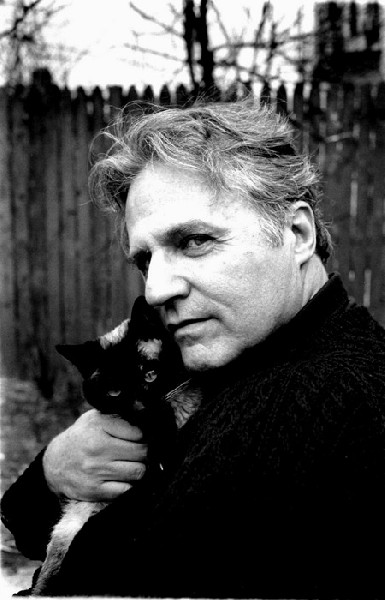

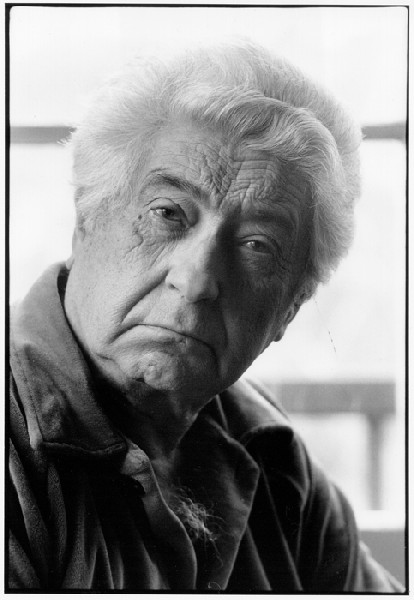

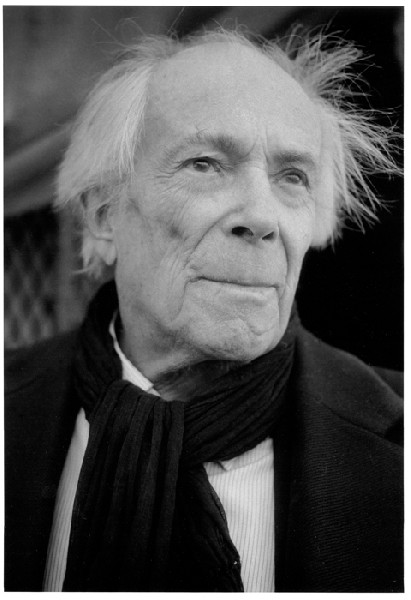

A close friend and someone I highly respect, Ben Maddow, commented in a preface to one of my books, on how the famous faces I photographed looked anonymous and the more anonymous faces had this aura of importance, as if they'd switched places with one another.

Now Ben certainly knew a thing or two about faces and portraits. He'd written this tome about the history of portrait photography and authored biographies of Ed Weston and Eugene Smith. He made a name for himself as a distinguished and sought-after screenplay writer with titles such as The Asphalt Jungle and The Unforgiven; and then he had to go underground when the Hollywood Blacklist hit and ghost-wrote Johnny Guitar. But my introduction to Ben was through his poetry. He started out in the '30s and by 1940 had published a highly remarkable long poem, "The City," which Ginsberg credits as a major influence on "Howl." That's what he told me. Ben confirmed in my mind that I was on the right track with my work.

So when this slot opened up at Pierre Menard Gallery, I jumped at the opportunity. This was what I was hoping for. There was adequate wall space to mount a really big show. So now I had the incentive to move forward. The prints were already made and sleeping in boxes from two years earlier, 100 in all and the grouping was called Souls, for I felt each face, each person, had a story to tell and brought together, their voices and likenesses would be harmonious as a whole.

Also the effect I was after had a lot to do with the way the pictures were hung. Three and four tiers, all mixed up. One viewer on opening night came up to me and remarked how all these faces appeared so friendly and familiar, and he'd never even seen my work before. I'll always remember his words. A week later when Mark Feeney's review appeared in the Boston Globe, it affirmed what I felt deep inside all along. He perceived exactly every nuance and pitch of how these pictures interacted with each other and his review -- a first for me -- was like hitting a home-run right outta the park.

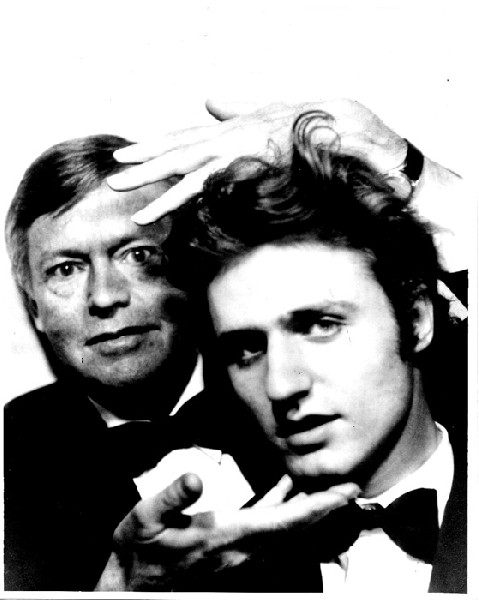

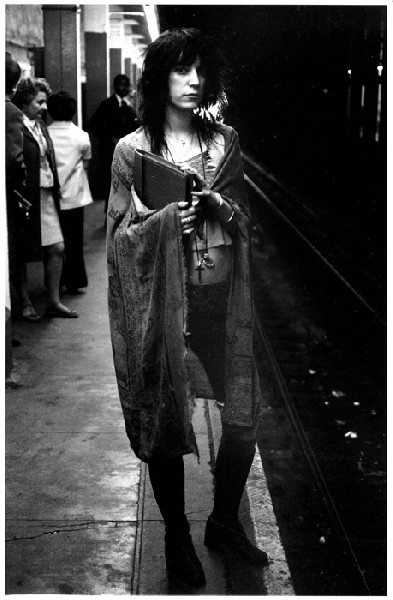

CG: In a recent issue of Time Magazine they published your photo of Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. What was your impulse and instinct to photograph them? Did you have a sense of their importance? Or was it just a random process that with time the image would take on such significance? In what sense was knowing and hanging out with your subjects an important part of the work? How was it different from the process of other portrait photographers?

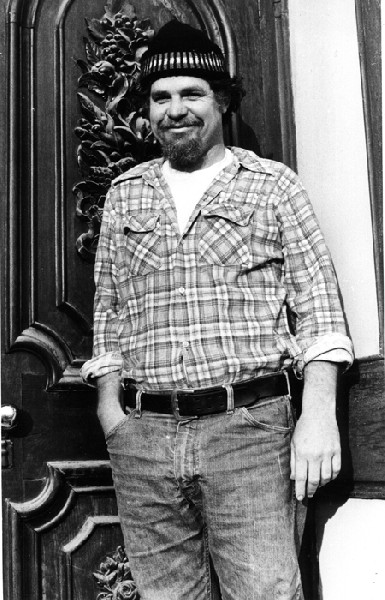

GM: I think you hit upon something here I hadn't previously dwelled on. Back when I first started in '69, I always had my Nikon with me wherever I went, so it was quite easy to document everything I saw and the people around me. I was never on assignment and only once was I ever assigned a shoot from a magazine. In one way that put me in situations of limited means.

I didn't have access to the truly famous. Otherwise, I just couldn't compete but that wasn't really on my mind. How was I to know some of those friends I did photograph would become famous someday? I always had this archivist sensibility early on, I wasn't like thinking I was making "art."

Charles Henri Ford, in an interview a mutual friend Ira Cohen made with him about my work, remarked that "Gerard has archival consciousness." His exact words. Well, he was basically passing the baton to me because we both had the bug, so that was a pretty poignant remark and it certainly made me conscious of the fact what I was doing all along.

My modus operandi from the start was photographing artists and poets because I felt it would be important for a later time. How you could look back at yourself through time and recollect. It was like gathering evidence for what might disappear.

For instance, in that photo of Patti and Robert, they were new friends and I was drawn to their creative energy and I wanted to document them in a way that would convey a sense of who they were as a couple and as a team. I also have pictures I took of them separately. Neither of them had even reached the beginning of their fame when these pictures were made which I guess makes them unique. But I have lots of pictures like that. In a sense, I was photographing the past in real time.

CG: I like that idea of photographing the past in real time. The work became important in large part because of the life you opted to live. There was a combination of serendipity, cunning and opportunity. Regarding the portfolio of images in the current exhibition (100) a friend commented to me "Wouldn't you like to have been a fly on the wall in that scene." Which in a sense describes your situation and the work.

Most people in the Warhol scene were too busy partying and being famous for 15 minutes to create their own serious work. The survival and burnout rate has been significant. But you lived to tell the tale. The title of the show might have been Call Me Ishmael. Flesh out your instinct to record the world you lived in. How does one straddle the line between being in the scene, one of its characters and stars, as well as objective enough to document and archive what was going down?

GM: I don't know about the life I opted to live. I was poor as a church mouse, but I wasn't going to let that stop me from doing what I felt needed to be done and with the limited means at my disposal I would make optimum use of the one camera-one lens. Don't forget I wasn't working out of a studio. I was out in the field, as it were. I don't see "the fly on the wall" in relation to what I was doing. Some portraits are one-off; encounters on the street; that sort of thing. I do far less of that now. Others involved one or two rolls of film and considerably more time but I was comfortable with that. I was photographing mostly friends or people I'd just recently met. They treated the occasion seriously and that made the effort all the more worthwhile. But we keep coming back to this misnomer about the Warhol scene.

I wasn't taking pictures in the Factory to document the Factory. The overlap was barely a year and then I went out on my own. Yes, I guess, you could say I survived but I was conscious of that. Throwing caution to the wind was not my lifestyle although maybe it appeared that way to others. I knew when to withdraw. I knew when to keep one step ahead of the brink. I like your idea of calling my show, Call Me Ishmael but then I'll have to research what it all means.

Perhaps it'll stimulate my intellectual curiosity more! You see I never really gave second thought to these multiple roles. Yes, I'm a poet and a photographer, then as now, but being in the scene for me was to photograph it and 'it' for me was mainly making someone's portrait. I knew what I was doing would be important for a future time. That's the nature of being an archivist. Collecting. Documenting. Keeping pace with the pace around you. How important for a future time these pictures would be I couldn't really gauge, but I felt good doing it. Ezra Pound remarked once in a BBC interview how if an artist doesn't follow his curiosity, he's dead. Curiosity is the mainstay that keeps me going. Taking pictures. Writing poems.