Radvanovsky and Hvorostosky at Carnegie Hall

Marco Armiliato Conducts Brilliantly

By: Susan Halll - Apr 02, 2010

Marco Armiliato, ConductorSondra Radvanovsky, Soprano

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Baritone

National Philharmonic

Mozart, Overture to The Marriage of Figaro

Rossini, Resta immobile, William Tell

Verdi, Ernani, Ernani involami, Ernani

Verdi, Gran Dio, Ernani

Dvorak, Song to the Moon, Rusalka

Verdi, Favella il Doge, Simon Boccanegra

Verdi, Overture to Luisa Miller

Verdi, Act III, Scene I, Un ballo in maschera

Leoncavallo, Intermezzo, Pagliacci

Tchaikovsky, Final scene Eugene Onegin

Carnegie Hall

New York

April 1, 2010

Mozart, so deliciously devilish, opened the program at Carnegie Hall on April Fool's Day. The overture to The Marriage of Figaro heralds a composer of operas, none of which have lost their freshness over more than centuries. Mozart abandoned a middle section, leaving a spare, electrifying sonata with no development. A crazy day is about to unfold on stage in Figaro, where Mozart will merge for the first time the symbolic harmony between music and drama. That pointed the way to this evening of song with Dmitri Hvorostovsky and Sondra Radvanovsky.

The glistening National Philharmonic, under Marco Armiliato's baton, performed the overture with precision and wit, boding well for the evening of overtures, an intermezzo and especially song. Armiliato is a vigorous composer who was up to the task of conducting both Aida and La Traviata at the Met on Saturday.

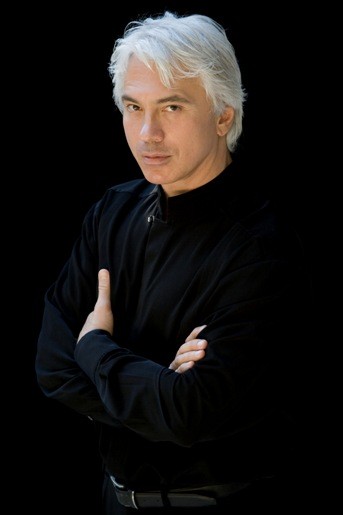

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, the magnificent Russian baritone, swept onto the stage in a form-fitting black velvet tux with a regular tie and white shirt, opening with 'Resta immobile' from Rossini's last opera William Tell. This was of course the beginning. He has a lovely low tessitura, veering to bass-baritone, and clearly enjoys the stage.

A glamorous Sondra Radvanovsky provided contrast in her black silk gown, the deep décolletage revealing white skin to echo the Hvorostovsky shirt.

Radvanovsky will now assume the position she deserves, front and foremost among the world's great sopranos. Hearing her in Il Trovatore, the node on her vocal chords was undetectable to the ear. Although she claims it did not disturb, she decided to have it removed.

Radvanovsky has said, "I feel like I'm really now coming into the meatiest point in my careerÂ…It's taken me a good four or five years to learn all aspects of my voice. Now I feel like I'm driving a Rolls Royce instead of some little Volkswagen." Tonight we heard a Bugatti Veyron. Listening to Radvanovsky in Stiffelio earlier this year, adjectives eluded.

Hvorostovsky has said he wanted to develop a Verdi voice, and he has. Radvanovsky was born with one. Her range is remarkable, from the dusky lower tessitura, to high notes that pierce the air and skewer you. Carnegie is her venue, for all the subtlety and glory of her voice is immediately evident. At the Met next year, where she is scheduled for Tosca and Il Trovatore, sit upstairs so that you can get a full sense of her voice.

The program continued with Hvorostovsky solo in Gran' Dio from Ernani, Radvanovsky in a musically delicate sprite's aria from Dvorak's Rusalka and then the poignant father-daughter recognition scene from Simon Boccanegra. Is this a to-be-wished-for prelude to their teaming on the opera stage?

Luisa Miller's "Overture in C Minor" opened the second part of the program. This overture is unlike any other Verdi wrote. It has one theme and is built on modulations, not a succession of contrasting melodies. Verdi clearly intended to suggest Germanic symphony music rather than the usual, Italian potpourri.

Hvorostovsky, now in a black shirt, and Radvanovsky in a bronze silk gown perilously cut in front and back, performed Act III, Scene I from Un Ballo in Maschera. Verdi had become interested in French grand opera and mixed the lighter side in the character of Oscar. In the scene performed, the intense, interior version of Italian serious opera is still on display.

The Pagliacci intermezzo was performed perfectly by the National Philharmonic. It follows the arrival of Tonio, the jealous husband whose words are accented by muted brass, reminiscent of Verdi's Otello in a solo for double basses and a sinister tritone.

In the intermezzo the sad melody of the preceding arioso, the celebrated Vesti la giubba returns in altered and depending on diminished 7th chords. Chromatic progressions lead to the melody suggesting unity of life and art.

Following instead was another unification of life and art, the eagerly-awaited final scene from Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin. How can Tchaikovsky have imagined that this opera would be heard by a few cognoscenti in their living rooms? The music of the finale recalls the beautiful phrases early in the opera, associated particularly with Tatiana's girlish love of the fop from the city. Radvanovsky has become no mean actress, with moves and gestures syncing happily with her voice. Whether a singer of her quality needs these add-ons is debatable, but they are a pleasure to see developed.

For her first encore she performed Visse d'arte from Tosca, which she will perform for the next two months in Denver in preparation for her assumption of the title role at the Met. As soon as she began, any doubts about the suitability of this role for her voice disappeared. Which soprano sings the aria better?

Hvorostovsky ended the evening with an unaccompanied Russian folk song. Because Tchaikovsky did not include folk song references in Onegin, he was sometimes accused of being un-Russian. In Hvorostovsky's large, exciting voice, going tender from time to time, Russian was beautifully delivered.

It was an evening to treasure with incomparable singers in a truly great Hall.