Reports on Southern Africa: Part Four

Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 03, 2008

On the way from Victoria Falls to Hwange National Park, we flew over clouds to avoid turbulence. As we flew in and out of clouds, their shadows reflected on the green tapestry below. I was a painter with a camera. I could see why this landscape, dotted with huge puddles, inspired the arts and crafts of the local people. Seasonal changes in colors inspired the textiles. Batiks simulated the lush foliage of the bush, as well as its parched landscape. Flowers, leaves and pods informed the basket patterns. Zebra stripes, giraffe spots and animal horns appeared in myriad forms in a variety of crafts.

A mini van delivered us to our camp in the northeast corner of Hwange, Zimbabwe's largest game reserve, resting on the edge of the Kalahari sand mass. To make its arid climate a hospitable habitat for wildlife and vegetation, a system of pumps had been installed to carry underground water to water holes throughout the park. Our tented camp offered a clear view of a watering hole, the broad savannah grasslands and acacia woodlands.

My mind drifted to the early inhabitants of these lands that have survived the unpredictable turns and twists of history. The indigenous Zimbabweans were the hunter gatherer Bushmen, who are called the San. Between 200BC and AD1000, Bantu-speaking agriculturalists and herdsmen migrated south, absorbing and displacing the San. In the ninth century the cattle herding ancestors of the present Shona Tribe, which makes up 60% of today's inhabitants, arrived. They constructed towering houses of stone as they grew in wealth and power. The word "Zimbabwe" means "House of Stone". Fleeing from Boer trekkers, the Ndebele, the second largest language group now, settled in the west of Zimbabwe in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Meanwhile Portuguese explorers, English missionaries, ivory hunters and gold miners arrived in search of wealth. In 1893 the Shona and Ndebele, traditional enemies, joined forces to drive out the Europeans. Under fire power many of the settlers were killed and Zimbabwe was ruled by and for the British for the next 85 years. Britain named the country Rhodesia after Cecil John Rhodes, who made a fortune in diamonds in South Africa, and extended British influence from Cape Town to Cairo.

In 1957 the Southern Rhodesian African National Congress emerged to free the country from European colonial powers. In 1963 the nationalist movement split into the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African Peoples' Union (ZAPU). Furious rivalry developed. The whites pressed the British government to give Rhodesia independence. Ian Smith, a farmer, became prime minister of Southern Rhodesia in 1964, and secured independence in 1965.

Shona and Ndebele guerilla forces organized in 1966 and began rural infiltration on Maoist lines. In the mid 70's Smith tried to reach out to the two liberation groups. But they were not interested; instead, joined forces as the Patriotic Front, leading to an all party conference and signing in London in 1979. Free elections followed in 1980 and Robert Mugabe became Zimbabwe's first prime minister.

Zimbabwe was Africa's 50th state to gain independence, but at a high cost. In total 27,000 people died, and two-thirds of Rhodesians left. Although Mugabe assured the nation that there was place in Zimbabwe for both winners and losers, the commercial farmers, who stayed, have all lost their farms. Since they were the economic backbone of the country, turning their farms over to unskilled labor has led to scarcity of goods and extreme poverty. Mugabe is still at the helm, but leads the country with no tolerance for opposition; violence is his response to any challenge to his authority or worldview.

Our camp did not reflect the country's scarcity of goods, as all food is imported by the private concessions. During our first game drive, we saw elephants, zebras, elands and buffalos. An unusual sight was the giraffes with their legs extended on both sides so they could crouch to drink from a watering hole. While their long necks and legs make it easy for them to eat tree top foliage, they present a challenge for drinking. As we neared the river to watch the sunset, tree silhouettes reflecting in water were a spectacle to behold. This was a wonderful setting for a birthday drink, yet so different from where I was a year ago, walking through clouds in Machu Picchu. We returned to camp for a delicious dinner: Fruit salad in Amaretto was the first course, followed by beef steak, roast potatoes, pasta, and creamed spinach and for dessert birthday cake enjoyed by all.

The following morning, our intended nature walk, instead, turned into a rhino chase after our guide spotted tracks. Donning his gun and ammunition belt, the guide scattered some powder in the air to determine the direction of the wind. We had to walk in the opposite direction of the wind, so that the rhinos would not smell us. They have a strong sense of smell and hear well by constantly moving their ears like antennas. We tiptoed into the bush until we saw at a distance two rhinos, a male and a female. Unfortunately they sensed us and moved away.

Back at camp, a lecture provided information on the park, which is named after chief Hwange, of the San tribe. In recent years, army guards from Zambia have come to hunt rhinos for their horns. In response, the park was declared, an Intensive Protective Zone (IPZ) and is monitored by guards. Because of the scarcity of rhinos, killing one in Zimbabwe carries a 15-year jail sentence. The elephant population presents a different challenge; their numbers far exceed the Park's capacity of 15,000. Elephants are culled periodically because they keep the trees stunted and destroy the environment. Consideration is underway to join with other parks to expand protection for elephants.

Our school visit provided insights into Zimbabwe's poverty. After traveling about an hour in our land rovers, we transferred to an ox cart to get to the Ngamo School, which serves a village of 800 people. I had to sit on a straw floor mat in the cart, because the higher sides were reserved for men. The primary school has 226 students, attending first through seventh grades. There are about 35 students per grade. Only eight or nine of the graduates will go on to Form One and high school because there is none nearby, and sending a child to live and attend school in a town is beyond the means of almost all of the villagers. Of those who are able to continue through high school, only three or four will attend college. Most children stay around the homestead to work and get married.

Children have breakfast at home before they arrive at school at 7AM, some walking as far as four miles. Most do not eat again until they go home at 4 PM. It is not only the school that can't provide them with lunch, their homes lack food as well. Due to excessive rain, many crops have been ruined, depriving villagers of basic foods such as maize, sorghum, millet and vegetables. Some of the students are too weak to walk to school, so they stay home. There is no medical clinic. In case of serious illness or an accident, transportation to the nearest facility is by donkey or oxcart; a train runs once a day to Victoria Falls for those who need hospital care. Many die before they are treated.

Children in the fourth and fifth grades sang, danced and drummed for us in their classrooms. Young boys had amazing dexterity on the drums. They all knew English, and wore uniforms, although some were without shoes. We visited with the school principal and the teachers, all of whom wore neckties. The school lacked any playground equipment; children played tag in groups during recess. Rows of white rough stones divided the sandy schoolyard and were used for students to line up by grade before going into class. We left school supplies as gifts, but what these children needed most was food and vitamins. I suggested we skip a meal or two at the camp and donate the food to the school, and was told that if Mugabe got wind of it, he might shut down the concession.

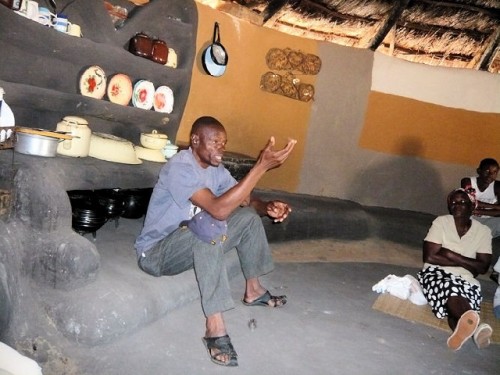

A short walk down the path brought us to the headman's homestead, one of twenty-seven in the village. He welcomed us with his wife, stepmother, son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter. The headman's immediate family has nineteen people; it expands to forty during holidays. He received us in the communal kitchen, where we sat on cushioned low benches around the perimeter. The women and children sat on a reed mat on the floor. They were of the Mattebelle Tribe, a branch of the Zulu. They spoke Cyndebelle. The headman explained some of the traditions of the tribe. The head of household gives oxen or money for the son's bride, who leaves her homestead to move in with her husband's new family. At death, men are buried in the front of the homestead and women in the back. The house of the deceased is torn down to release the spirit. However, traditions are changing as more couples opt for white wedding gowns instead of tribal dress.

In the evening we were treated to traditional dancing and drumming around the campfire. The staff performed for us two Zulu dances, a tango and a miners' dance, which featured percussive footwork, imitating the cleaning of mud off their shoes. Displaying individual showmanship, these dances are performed at weddings and funerals, where people dance to a frenzy to help spirits in their journey. We joined in the final communal dance. The farewell dinner, which began with a stuffed tomato appetizer, continued with a choice of grilled meats, polenta, stuffed acorn squash, baked potato and cake with custard sauce.

On our final morning we went for a nature walk, which acquainted us with a variety of trees: Stinga, vegetable ivory palm, ebony, teak, wild date and acacia, used for making sewing needles. We walked by a mud bath that had an entire elephant's body print in profile. We learned that the elephant dung is used by the local people to stop nose bleeds when inhaled and to ease labor and childbirth pains when consumed as a hot drink.

After a delicious brunch back at camp, we drove to the airstrip and flew to Victoria Falls.