Edith Wharton's The Mount

Berkshire Literary Festival July 23-25

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 04, 2010

There was vigorous Spring Cleaning in Lenox preparing for the seasonal opening of Edith Wharton's The Mount, a renowned historic home, which she designed and built in conjunction with the architect Ogden Codman, Jr. in 1901-1902. They collaborated on Wharton's first book The Decoration of Houses, in 1897.

The book became a best seller, the first of many for Wharton who was born Edith Newbold Jones, on January 24, 1862 and died, in France, on August 11, 1937. The Mount is a monument to her legacy as the most successful author of her generation. The estate embodied many of her ideas about progressive interior design and formal gardens. But it was not a happy home. She occupied it for only nine years. Wharton emigrated to Europe after her marriage to Teddy Wharton, a dozen years her senior, ended. She returned to America only once to receive an honorary degree at Yale.

The philandering Teddy, who was not her peer intellectually, embezzled from her to support mistresses. When they separated she wanted to keep The Mount. He had power of attorney and, without her knowledge, sold the property to the richer Shattuck family. There was a second owner until it was bought by a developer. From 1978 to 2001 it was leased to Shakespeare & Company. A separate board Edith Wharton Restoration was founded in 1980.

Increasingly there was a conflict between the needs of the theatre company and an effort to restore an historic landmark. After extensive renovation it opened to the public during the centennial year of 2002. The departed Shakespeare & Company acquired a nearby estate, originally the Lenox School for Boys.

S&Co. was founded by Tina Packer and the head of Edith Wharton Restoration was Stephanie Copeland. One may just imagine the clashes of those remarkable women. Last summer Packer discussed the complex history of her company during its many productive years at The Mount. She loaned to me a thick binder of documents including court papers and media reports of that complex separation. It is a dense but fascinating history.

Not that going their own way solved the problems. If anything they intensified. Copeland executed the acquisition of half of Wharton's library under seemingly favorable terms, in 2005, for $2.5 million. There were already loans and lines of credit from Berkshire Bank. By 2008 the debt reached $8 million and The Mount missed several payments. The bank issued a default on the loan. Foreclosure proceedings were initiated. Through reorganization the staff was reduced to a minimum and Copeland resigned.

On the other side of Lenox, just over a year ago, S&Co. announced that it was some $10 million in debt. This was revealed under the new artistic director, Tony Simotes. Packer remains with the company as a performer, director, teacher and fund raiser.

In these challenging economic times it is significant that two major cultural institutions, The Mount, and Shakespeare & Company, are fighting for their survival. For both organizations it is encouraging to report that the worst appears to be behind. But there is a day to day struggle to raise funds for operating expenses and programming while reducing debt. It may be a decade before they start to build endowments and initiate crucial expansion and renovation.

The Mount and S&Co. are essential components of the unique cultural resources of the Berkshires. During high season the Berkshires are the epicenter of American culture. The dark side is that during hard times a heady mix of Tanglewood, Jacob's Pillow, several major museums and theatre companies are all appealing to a limited resource of charitable foundations and individuals. On the positive side, acknowledging common concerns there is ever greater communication and synergy. The cultural leaders meet regularly to compare strategies and work on coordinated programming. Audiences, particularly during the off season, are the direct beneficiaries of this networking.

In 2001, Susan Wissler, a tall, athletic, understated attorney by training, joined The Mount as an administrator. She took over as Executive Director, in 2008, when Copeland resigned. Slowly she has been getting the organization back on track as well as initiating efforts to expand the mandate of the historic site.

In the spirit of Wharton, from July 23 to 25, she is launching The First Annual Berkshire Literary Festival. There will be a series of jazz concerts on the terrace featuring local musicians on Friday and Saturday evenings. A special exhibition, Dramatic License: Edith Wharton on Stage and Screen will be on view. Last season theatre returned to the Mount with Dennis Krausnick's adaptation of the Wharton story Xingu. That was a success and this season there will be a staging of another Krausnick adaptation of Wharton's sexy story Summer from August 18-29. Last summer's play was a hit so the run this season has been expanded.

The play will be presented in the drawing room of The Mount which has a limited capacity. Wissler hopes to renovate The Stables as a more adequate space for performances. It was used in that capacity by S&Co.

Recently, we met with Wissler for a tour of the grounds and house. At the beginning of the meeting I asked how much time she had. We left her some three hours later after what proved to be a truly remarkable experience. As we strolled along the path to the house we were informed of the many plantings and landscaping ideas of Wharton which are being brought back to her original intentions. She urged us to come back in a few weeks when all of the thousands of bulbs, many original heirlooms, are in bloom.

"She loved the sound of water" Wissler explained as we passed along running brooks. From the formal gardens and porches one can look off at what appears to be a large pond. It was not original to Wharton and is the result of busy beavers.

By the end of the day we had examined every nook and cranny of the house. Including servants quarters and areas not open to the public. Wissler even took us up to the roof and its cupola for a panoramic view of the estate and its 49.5 acres. The original site was 113 acres of farmland with another 15 acres added later. While reduced it is a lot of property to manage. During the summer the staff increases to include a grounds crew.

A recent effort has been to expand membership. One perk is to enjoy the grounds for walks and picnics. Daily admission to The Mount is $16 while children under 18 are admitted free. Membership includes invitations to openings and receptions.

It was a glorious clear, bright, brisk day to experience The Mount. As we strolled along I asked Wissler what background she had in architecture and historic preservation. "None" was her frank response. She majored in psychology at Brown before law school at Columbia. "Perfect qualifications to run The Mount" I quipped. Particularly, the psychology part. When I asked her to recall those dark days in 2008 it was poignant and insightful when she was overcome with emotion. It was a compelling signifier of the human toll of crisis as well as an indicator of the depth or her commitment and that of the staff. She described how even after they were let go a number of individuals helped out returning as volunteers.

On a knoll near the Italian gardens we observed some tomb stones. "That's the pet cemetery" Wissler explained. "She loved her dogs and animals. People ask us to spread ashes here and we are fine with that." It is indeed a restful place.

While The Mount is a grand house and architectural treasure, compared to the Newport Cottages and great American estates, it is not ostentatious.

"It was built as a writer's retreat" Wissler said. "It was not a show place and is sited away from the road. You will see when we are inside that it was built to a comfortable scale. It is where she lived and worked. There are large windows with views of the garden and it is filled with light and air. She wrote in the morning facing the gardens and edited on the other side of the house in the afternoon."

Through her early years Wharton spent time abroad. It is where she developed notions of design and architecture which inform the house and gardens. The best view of the house is below when approaching from the gardens. We look up at the house sited on a low hill above. On the bright sunny day when we visited the masses of the house were sharply articulated. It is odd that although Wharton strove for balance and symmetry the house is off kilter because of the wing of servant's quarters. It seems like a poor design decision. The women servants lived in this wing in what proved to be comfortable rooms with amenities. The men were housed above the stables. There is also a gate house, now used for administration, green house, potting shed, and cottage.

Ascending to the terrace, which wraps around the front and side of the house, we examined the details of window surrounds and ornamentation. Much of this seems taken from Palladian pattern books via Georgian country houses. Wharton was a great writer but no Jefferson. Apparently, she resented the excessive bills from Codman and they parted ways. It would be good to know precisely what aspects of the house reflect her ideas.

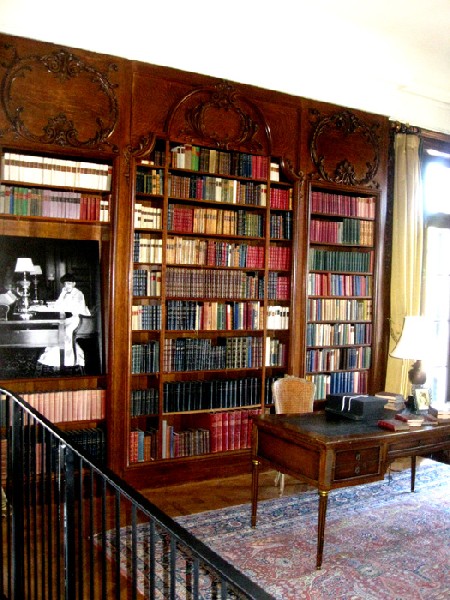

From the garden side we approached the actual entrance to the house. There is a brick walled courtyard. The front is austere and imposing. Through rusticated marble columns one enters a formal foyer. There visitors were greeted by a servant and admitted or not. This wide, narrow space is mirrored above by a galleria that is flooded with light. Along this promenade are entrances to separate rooms including a drawing room, dining room, library, and then the private quarters.

The dining room is quite intimate for such an elegant home. The table has chairs for six. It seems she did not entertain at a grand scale, although she hosted famous guests.

With the exception of the library, which visitors view but may not enter, none of the public rooms are roped off with stanchions. We found them stored in the attic. Wissler insists that visitors have the run of the house. And yet she reports minimal theft or damage. While the furniture is not original we get to experience the house much as Wharton intended.

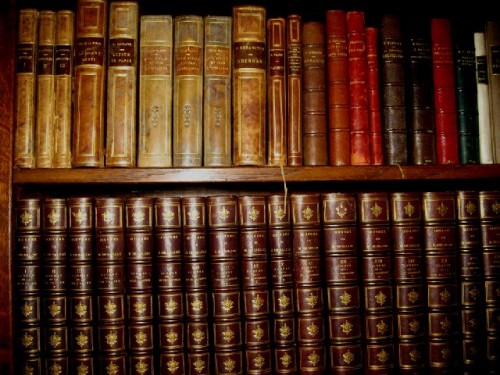

In the library we were greeted by Molly McFall. She discussed at length the history and treasures of the books. It seems that about half of the Wharton library of some 4500 books was lost during WWII. They were destroyed when the warehouse in which they were housed was bombed.

While the shelves of the library are filled with rare, leather bound volumes it is not the entire collection. Others are stored in a smaller building. McFall suggested that Wharton would have had many bookcases throughout the house.

It has been speculated in the media why Copeland and the board got themselves in such a pickle acquiring the Wharton library for $2.5 million. An argument is that an adequate number of leather volumes could have been bought to fill the shelves at a fraction of the cost. Other than the fact that Wharton owned them of what particular interest are they?

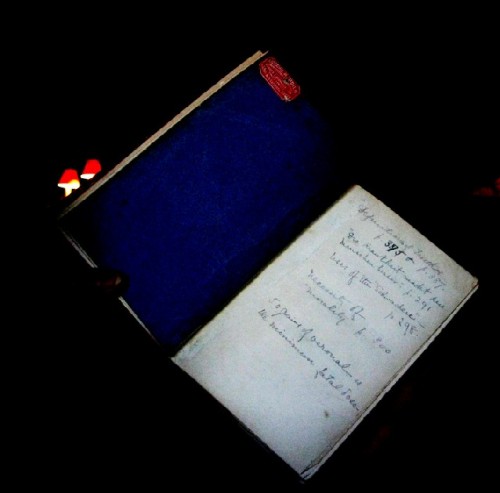

The Beinecke Library at Yale University houses some 50,000 items in its Edith Wharton Collection. McFall stated that Wharton scholars do come to examine the books. She showed us examples of books that Wharton annotated. She asked Astrid to translate some inscriptions in German. Wharton spoke French fluently and was adept at German and Italian. She liked to read in the original languages including Russian. The books were an important aspect of her persona.

Eventually, when expansion and renovation occurs, there are plans to create a research and study center with better access to the books. In the long term the library will prove to be a valued asset. The controversial acquisition, however, brought the institution to the brink of extinction.

Exploring the servant quarters and private rooms of the house we were intrigued by the plumbing and amenities. For 1902 Wharton was a modernist. The house was entirely electric and one of the first with telephone service. Mr. Westinghouse lived just up the road and The Mount had access to his private generator. There is a large bathroom and queen sized tub off her bedroom. Teddy's dressing room is located between his and her bedroom. At the worst of it there are tales of notes slipped under the door. It is typical of the period that such aristocrats occupied separate bedrooms. It was an era when women were expected to perform conjugal duties.

As we ambled thorough the servants' quarters Wissler casually commented on ghosts. It seems that Wharton wrote some spine tingling ghost stories. She reported that paranormals had been invited to the house which they found to be quite active. We must return one night for a bit of table tapping. The Mount conducts organized ghost tours.

It was while residing in The Mount that Wharton wrote one of her most successful books The House of Mirth. But it seems that for during that time there wasn't much joy. She departed for Europe with the dogs and servants. Wissler commented that she was very generous with her employees and looked after them in their elder years.

In France Wharton made her mark during the Great War as one of the few allowed to visit and report from the front lines. That happened, Wissler commented, because she was viewed as a writer and not as a journalist. She was also active in refugee relief and the care for orphans. Truly, what a remarkable woman.

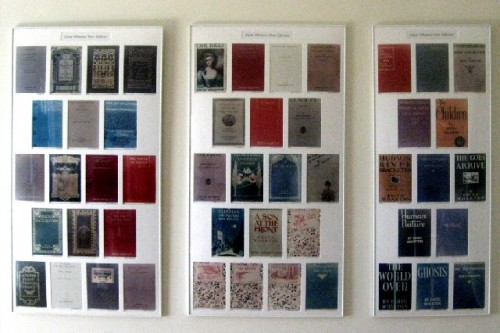

In one room there is a wall with the covers of her 40 books. I asked Wissler how many she has read. "I have gotten through about 40%" she replied. Even by today's taste and standards Wharton is still a good read. The Mount is a stunning monument to her triumph and tragedy.