Namibia: Part Three

Walvis Bay and the Skeleton Coast

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 07, 2015

After an early breakfast, we left our campsite for an 8:30 flight from Geluk to Walvis Bay. Once again traveling in a small plane, we followed a scenic path along the river, soaring over the dunes, and reached the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. We then continued north to the Skeleton Coast, named after the many shipwrecks embedded in its sands. As we approached Walvis Bay Airport in the late morning, we sited our first shipwreck in the sand.

Walvis Bay, a natural deep-sea harbor, was controlled first by the Dutch in the late 18th century, then by the British, who ceded it to the South African Union, where it remained until 1994. Once a center for the whaling industry, it is an important fishing port and harbors extensive salt fields.

To see the bay’s highlights, we strolled along the palm-lined coast with its up-scale homes and reached a reed-fringed fresh-water lagoon, an important wetland for coastal birds. Flocks of flamingos in different positions — standing, walking, feeding, and swimming — were a sight to behold, their numbers multiplying as their shadows reflected on the shallow waters.

Another point of interest was a plant where salt is harvested from the ocean by evaporating water in large containers, then piled into big mounds, processed, and transported by the truckload for industrial use. We were allowed to see the salt pyramids only from a distance because of safety concerns, due to the heavy equipment used around them.

The Bay’s oldest building is the Rhenish Mission Church, prefabricated in Hamburg in 1879 due to a lack of local building materials. Services for natives were held here from 1881 until 1966, when the church was taken over and restored by the Lion’s Club. The Bay’s oldest existing building, the church is now a national monument.

Following the tour of highlights, we drove to a scenic restaurant called the Raft, which jutted out over the ocean, with sweeping views through large picture windows. Lunch consisted of creamy butternut squash soup and “fish trio” — grilled fillet of kingklip, monkfish, and butterfish — or prime beef rump, accompanied by baked potato and salad. The fish platter arrived with little flags on each fillet, identifying the variety of fish.

For dessert, in honor of my birthday, a special surprise cake arrived, courtesy of Joel. Not realizing it had been decorated with trick candles, I blew and blew as I made a wish without success, with much laughter around me. Ordered from a French pastry shop, the delicious cake was rich and moist with a caramel center, covered with Parisian chocolate cream, and finally coated with a chocolate sauce. The remaining half of the cake went back in its box, as it was too rich for seconds. We delivered the box to a soup kitchen on our itinerary the following day.

Continuing our journey in a minivan, we arrived in Swakopmund, Namibia’s second largest city and our overnight destination. Founded in 1892 as a main harbor during the German colonial era, the city is situated between the desert and the sea. Due to its big shipping industry, South Africa hung onto the town even after Namibia’s independence in 1990. After his release, Mandela had Swakopmund returned to Namibia.

Driving through the picturesque town, reminiscent of Bavaria’s old-world charm, we arrived at the Hansa hotel to a champagne welcome in the lobby. My room with a patio faced the inner courtyard of the two-story hotel. Tropical trees and flowers, interspersed with umbrellas for shade, along with a fountain, enhanced the charm of the courtyard. Although attracted by the setting to relax with a book, I went back out to explore the city on my own during our free time.

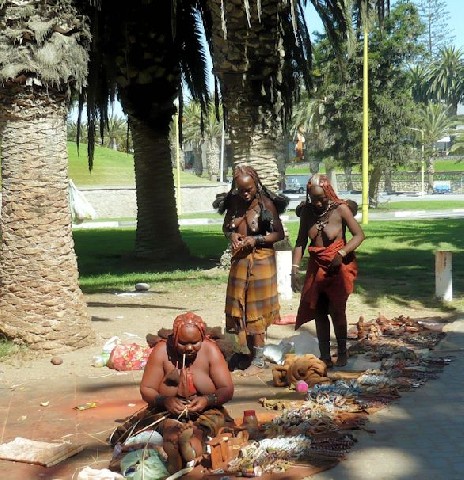

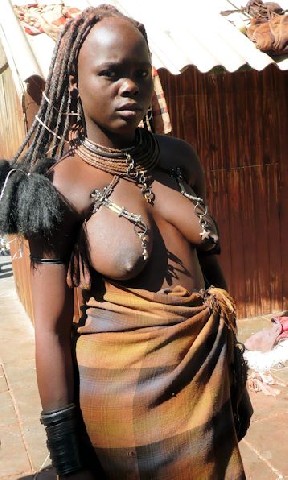

Near the Crafts Market I came upon a group of women spread by the roadside, selling their jewelry while they worked and watched over their babies. They had ochre-colored skin and hair, were naked from waist up, and sported a lot of jewelry, mostly from iron and ostrich shells, around their necks, arms, and ankles. While I had seen photos of Himba women in National Geographic magazine, I did not expect to encounter them in their traditional attire in the city. Surprised by this discovery, I approached one of them to find out if I could take pictures, provided I bought some of her jewelry. Upon her affirmative response, I purchased a bracelet and a necklace from two different women. There was no need to bargain, considering the favorable exchange rate of 11 NAD (Namibian dollars) to one US dollar.

The word “Himba” means “beggar,” referring to the semi-nomadic lifestyle of the Himba people, who follow a conservative way of life in the face of modernity, because of their isolated nature in the remote northwest of the country. Throughout the year Himba families move in search of grazing land for their cattle. The women cling to the long-established tradition of applying red ochre, a beauty product prized for its warm red hue, to their intricately braided hair, with ends teased out into fuzzy balls, and also to their skin.

Due to the unexpected time spent with the Himba women, I cut short my visit to the Crafts Market in order to get to the Swakopmund Museum before it closed at 5 pm. The privately run museum has a botanical display of the types of vegetation and indigenous plants in Namibia. Also on display are an original pioneer ox wagon, the carriage of the last German governor, and a working model of a twin locomotive. The geological section has minerals and fossils from all parts of Namibia, while an archeological section sheds light on the prehistory of the country. An ethnographic exhibition focuses on the emergence of the modern Namibian nation against the traditional background of the various ethnic groups.

Cafes and restaurants along the harbor filled with locals and tourists as markets and stores shut down. Enjoying a leisurely walk by picturesque half-timbered houses still home to descendants of German families, I returned to the hotel.

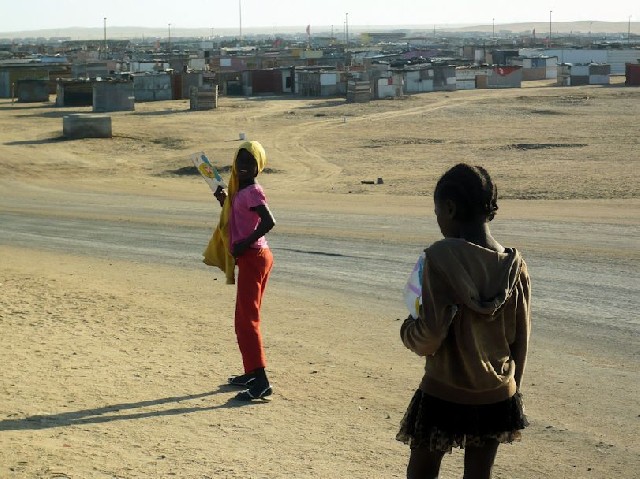

In the morning we toured the township of Mondesa, with its shacks built outside the city for needed slave labor. We visited a soup kitchen, where women in our group helped peel vegetables for a big pot of soup for children in a nearby kindergarten, while men worked in the vegetable garden. We also helped serve porridge to some forty children for their mid-morning break, following which we left for our visit to an elementary school.

Selected students from different grades welcomed us, dancing and drumming. We met the principal and visited two sixth grade rooms during instruction in math, English, and Afrikaans – the former the official language, the latter the one commonly used in addition to German and indigenous languages. We left some supplies with the principal to be distributed later, as children attend school in two shifts — morning and afternoon.

Walking through the township, we reached the home of Auguste Christa, who specialized in healing with natural herbs. She showed us some of her remedies, such as boiled roots for arthritis pain and powdered animal pellets to induce labor. She used tortoise shells to keep her powders in and a jackal’s tail as a powder puff.

Then we visited a Herero woman, who cared for orphaned children and youth, ranging from a baby to a 24-year-old. She was in her Herero costume, adapted from a long Victorian dress under pressure from missionaries to cover up; her hat resembled cow horns at each end. To support her efforts to care for children most of whom had lost parents to HIV, I purchased one of her fabric dolls, dressed as a Herero. “Drying up HIV funding a ticking time bomb” read the headline of a newspaper in her house.

Lunch was also at the woman’s house. We sat at a table with two boiled sheep heads, accompanied by home-made bread and boiled and pureed white corn at the center. We broke off pieces of meat and dipped them in gravy before popping them into our mouths. This communal way of eating took some getting used to, since we had to negotiate all food by hand, without any cutlery.

Initiated by Namibia’s President, low-income housing with indoor plumbing is under construction. Many of the residents work in the mines and are bussed to and from work in twenty-hour shifts. Since rainfall is rare in the area, water shortage is a big problem. There are long lines at water pumps; some operate on a ration system that requires swiping a card to find out the remaining water allotment.

Following this insightful township visit, we returned to the city for leisure time on our own. I opted to go to the Kristall Gallery, which has an impressive collection of minerals and gems, including the largest known crystal cluster in the world. A replica of an original mine with twists and turns in a cave provides a short simulated journey. There is also a jewelry boutique, in addition to a craft area to view the finishing of various gift items using gemstones.

Returning to the hotel, I decided to splurge and made a reservation for the dining room, set with white tablecloths. Much to my surprise, a paella dinner, with an appetizer of prosciutto and melon and a glass of wine, including tax and tip, cost around $20, which would probably have been enough for no more than a salad back home.

In the morning we left for Walvis Bay, for an exploratory cruise inside the protected lagoon. As cormorants fluttered above, the three-hour cruise took us to a 34 km -long sand embankment, crowded with seals basking on the beach or feeding along its shores. One came on the boat to the enticement of fish, while low-flying pelicans hovered around to be fed as well. Meanwhile we were treated to sherry and champagne, along with oysters on the half shell shucked on the premises, small sandwiches, and calamari. On our way back to the shore we saw many buoys, indicating that oyster baskets were suspended below; these are emptied once a month to keep them free of clinging sea plants.

Although we had been snacking all morning, I could not pass up the included lunch at the hotel. One of the specialties of the day was a local cod called kabeljou in Afrikaans. Two thin tender fillets were simply delicious.

Exploring the Skeleton Coast by foot was the last excursion of our regional itinerary. Heavy fog, raging currents, violent storms, and a lack of safe harbors are blamed for the 1000 estimated shipwrecks here. Off the coast we were able to see one partially sunken ship, which has become a nesting ground for cormorants. People who like this forsaken coast have vacation homes with water tanks on their roof. The natural phenomena of the desert include lichen fields; of the eighty species of lichen, twenty are endemic to Namibia. The rust-tinted plants turned green when they absorbed the water Joel poured on them. An endless number of mounds covered with small green plants blanket the rocky coastal desert, giving it a haunting beauty. Saturated with indelible images, we returned to our hotel to get ready for the next leg of our journey — Damaraland, known as one of Africa’s last true wilderness regions.

(To be continued)