Colombia: Part Two

Medellin and the Coffee Triangle

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 08, 2014

A short flight of under an hour brought us from Bogota to Medellin, a city of 2.3 million people, nestled in a narrow valley of sharp-edged mountains. Arriving at an altitude of 8000 feet at the airport, we descended to the city at 5000 feet, starting the day’s itinerary right away with a visit to the barrio of Santo Domingo Savio, reachable by cable car.

Medellin has Colombia’s only metro system, in recognition of the suffering which drugs have inflicted on it. We boarded a train with large windows at the sparkling new, well-policed University station to Acevedo, where we took a cable car to Nutibara Hill, one of the seven hills of Medellin. Paulo warned us that the cable cars never came to a full stop and that we had to jump out as our car slowed down. During the 10-minute ascent in the four-passenger car, I was just as absorbed in the beautiful Andean woman next to me as in the makeshift brick houses below. She was a house-cleaner, who commuted daily from her hill-side barrio to the city to work. She did not want her picture taken.

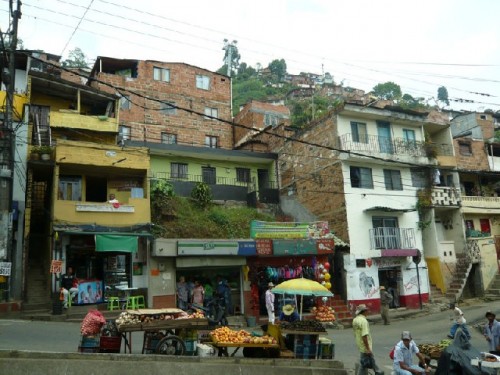

The reason for the neighborhood’s association with poverty became clear as we walked through its uphill streets. Laundry hung from balconies; vendor carts lined the uneven sidewalks, while shopkeepers waited for customers. Lively graffiti on the walls, including a portrait of Frieda Kahlo, added vibrancy to the streets, despite the poverty. Young people were also out and about on foot or on bicycles. We seemed to be a curiosity for people not used to seeing tourists; a little boy who should have been at school tagged along. Paulo explained that he was one of ten children, including a baby brother, and that his mother, who worked in the city, had probably not registered him for school. Although primary education is compulsory, the government does not enforce the requirement.

A friendly 85-year-old woman named Alicia leaned out of a window and signaled to us to come up. She led us up the stairs and through her neat two-room house, filled with religious icons, to a small rooftop deck. Blooming plants in earthenware pots, with two large fans nearby, lined one of the brick walls. In front was a stunning view of the city at a distance with cable cars running to and fro, and in the back a view of hills stacked with brick homes, some quite impoverished. Angela proudly told us that she had lived in the neighborhood all her life and raised seven children. We met the oldest one, who lived with her.

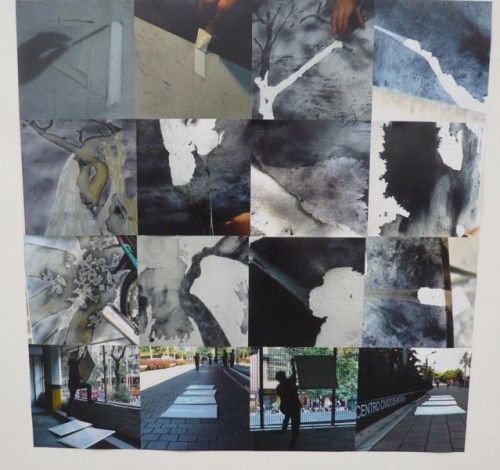

Our tour of a dramatic-looking library perched on the hillside amidst all the brick was equally interesting. Also serving as a community center, the library offered art classes. The top floor gallery exhibited the results of a competition among students on the environment. Many of the works were quite sophisticated; one in black and white with a touch of color especially caught my eye. Afterwards we had lunch at La Mesa del Barrio, a local community restaurant run by volunteer labor. The menu included soup, trout, and mixed fruit with ice cream. Tree tomato juice was a new flavor for me; locally grown fruit has a distinct tart flavor.

Riding the cable car back to the city, we met our bus just as it began raining. We inched along through congested rush hour traffic, finally reaching the Art Hotel, our home for the next two nights in an upscale neighborhood with lively restaurants nearby. At the end of such a long day, I felt exhausted and was in bed by 9 pm. Feeling refreshed in the morning after nine hours of sleep, I noticed the art in my room by local artists, also exhibited throughout the hotel.

After breakfast we headed for Guatape, a quaint colonial village in the countryside north of Medellin. On the way Paulo talked about the hidden difficulties of Santo Domingo, the barrio we had visited the day before. A no-go zone not long ago, the slum is now protected by groups of young men and women recruited by leaders to provide security for property in exchange for a weekly fee of $2-3 or $12 a month. This money is extorted; otherwise people find their property vandalized — a broken window or a stolen bike. Children as young as twelve are recruited by the security gangs, which the government tolerates despite the extortion, because people feel safe under their protection.

A scenic drive through rolling farmland to Guatape offered compositions of lush green fields of varying hues, depending on the crop, and farmers harvesting tree tomatoes at an orchard by the roadside. We stopped in Choco for a snack — a bowl of delicious hot chocolate and the local specialty, arepa de Choco, a pancake made of ground sweet corn, tomato, onions, and sugar. It came with a slice of fresh cheese on top and tree tomato on the side.

Embalse Penol-Guatape is a beautiful reservoir, created in 1978 by a dam to generate hydro electricity, which provides a major part of Colombia’s power. We took a boat ride over the reservoir, studded with isles and lined with resort homes, among which was Pablo Escobar’s burned down house. Another one of his houses with a commanding view of the reservoir has been claimed by one of his associates. Rising over the lake is El Penol — a 656-foot-high granite monolith, which can be scaled by a 649-step staircase built into a fissure. We enjoyed the surrounding views from the base of the enormous geological marvel, but did not scale it.

At a typical restaurant in Guatape we were introduced to bandeja paisa, the hearty traditional platter of the Antioquia region. Plates arrived with a mound of rice topped with a fried egg and surrounded by red beans, chorizo, minced steak, fried plantain, sliced avocado, tomatoes over shredded lettuce, and arepa, with a side of chicharrón (fried pork belly). Traditionalists feel paisa is rooted in the heritage of the agricultural community and therefore have been reluctant to modernize it with healthier and lighter versions. Ice cream with blackberry sauce topped this high calorie lunch, which was accompanied by “lemonade” made from limes.

The excursion continued with a stroll through Guatape, known for its houses featuring zócalos (the extended lower third of exterior walls adorned with relief depictions of village life). A visit with Nacho, a master zocalo artist, informed us about the craft. After a design is drawn and cut into the wall, it is filled with cement into a relief form, which is then colored using enamel- based paint. Designs depict the homeowner’s trade or some image the family identifies with. Flowers are a frequent motif, as Guatape has an annual flower festival. Painted two-passenger cars transported us down a cobblestone path called Memory Lane in commemoration of the houses lost to flooding during construction of the dam. The village’s attractive colonial church and colorfully ornate city hall enhanced the charm of its square with handicraft shops nearby. Satiated with lovely images, we returned to Medellin.

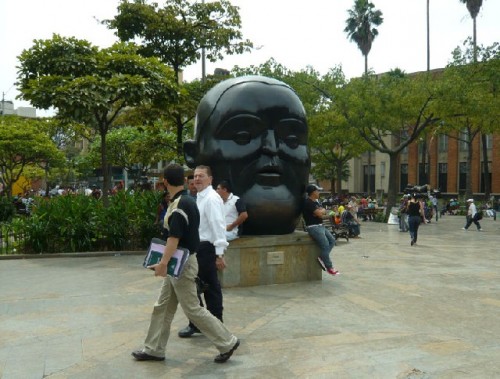

We spent the following morning in the city center. This is a busy place, where old, polluting buses are gradually being replaced. Botero Plaza, one of the major public places in the city center, is home to 23 sculptures donated by the Medellin-born artist. Many Colombians believe that Botero sculptures bring good luck, and thus enjoy milling about and fondling the voluptuous naked figures. The Antioquia Museum facing the plaza has a major collection of Botero’s works in addition to regional and international art. (See the article on Botero in the fine art section of BFA.) On the east side of the plaza is the Cultural Center, a remarkable gray-and-white-banded Gothic Renaissance structure. Built in 1925 as the region’s government building, the structure now houses a library, art gallery, and city archives.

For lunch we walked over to a local restaurant near the plaza. Here we enjoyed the traditional bean bowl topped with chips, with a side dish of rice with fried plantains, sliced avocado, and banana. Once again dessert was ice cream with raspberry sauce. Given the region’s mild climate, known as “eternal spring,” ice cream was a welcome choice following heavy meals.

From Medellin’s domestic airport we flew to Pereira on a very small plane. The 45-minute flight would have taken much longer by bus, Paulo explained, due to poor roads. Along with Manizales and Armenia, Pereira is one of three towns that comprise Colombia’s “coffee triangle.” Regardless of a heavy downpour, we stayed true to our itinerary, visiting a ranch where Creole horses were raised and trained. Our bus started to skid going up a muddy path. Cheerfully, we decided to walk the five blocks to the ranch through a landscape of farm houses, horses, and black buffalo, whose milk is used to make mozzarella cheese.

Horses were introduced to Colombia by the Spanish and had to develop different gaits to adjust to the new terrain. They begin training at the age of two and begin entering shows at around 3½. We watched a prize-winning horse gallop, trot, and walk, responding to the rider’s position in the saddle and pull on the reins. The variety of horses we saw ranged from a 13-day-old mare to a fully grown but small 5-year-old. Our skillful driver managed to turn the bus around in the meantime and delivered us to the Castilla Guest House, our home for the next three nights.

Hacienda Castilla was the old estate house of a plantation dating back to 1737. In the early 20th century, the large estates in the area began breaking up and the present owner inherited the property from her family, who bought it in 1926. My room, featuring old country furniture, opened onto a courtyard with a fountain and still maintained its original 18th-century door, which was hard to lock. As the only customers, we had the full attention of the staff and were treated to a delicious dinner of mixed chicken and beef kebab, followed by coffee mousse for dessert.

The next morning’s adventure took us by lush coffee plants on sloping hills toward Manizales, the second corner of the triangle, at an altitude of 4500 feet. We visited Hacienda Venecia, a plantation of 450 acres of volcanic soil, owned by a Colombian couple of Spanish descent and managed by their son. Our Sunday visit coincided with the workers’ day off; we picked coffee beans in their stead, with an eye for ripened red ones. Crossing a creek, we came to the main building, where we learned about the phases of coffee cultivation. The picked beans are floated to sort out high- grade heavy ones, which sink to the bottom, from low-grade beans, which stay afloat. Quality beans are processed for the export market — mostly Europe; Colombians drink the less expensive second- grade coffee.

Following sorting, the beans are skinned, washed, dried, and roasted. The length of the roasting period determines the strength of the coffee. They are packaged accordingly — Robusta for dark roast and Arabica for mild. To make decaffeinated coffee, the beans are treated in acid, which sucks out the caffeine. It was a revelation to learn that there was no natural way of producing decaf coffee.

Lunch at the plantation introduced us to sancocho, a thick regional soup with chunks of potato, manioc, and plantain. The spread also included a choice of beef, chicken, pork, corn, avocado, and arepa to add to the broth. Ice cream made with buffalo milk and topped with raspberry sauce was a delicious finale to a memorable farm meal.

Afterwards we toured the hacienda, a beautiful mansion built in 1910, with rooms still retaining their old Spanish country charm and surrounded by lush gardens with peacocks. Coffee production has decreased in Colombia, as farmers are switching to crops like manioc or quinoa to increase their income. Competition from other coffee producing countries, mainly Viet Nam, has led to the formation of cooperatives, which require local farmers to sell their crops at a fixed price. On the way back to Pereira we stopped in Santo Rosa, famed for its chorizo sausages, which we enjoyed during a poolside cocktail hour at our hacienda.

On our final day in the triangle, we drove in the direction of Armenia and visited Salento, a small 19th-century town perched on a plateau over the Quindío River. The historic town is awash in color with painted facades, doors, balconies, and hanging flower pots. A statue of Simon Bolivar graces the eponymous plaza, which also has an attractive church. The main street is lined end- to- end with souvenir shops and coffee houses. I bought a shawl hand knotted on a small triangular loom.

Visiting one of the coffee houses refined our coffee education. By smelling the different roasts before and after water was added, we chose the aroma we preferred for a cup of coffee on the house. We also learned the difference between café latte and cappuccino. In the former, hot milk is poured into the coffee and mixed, whereas in the latter, coffee and milk are slowly poured into a cup from separate pitchers, producing a granular foamy product. A design drawn into the foam of my coffee with a fine straw turned out to be the face of a bear.

Visiting Cocora Valley was a most exhilarating hike. We traveled to Cocora National Park in yipaos, colorful jeeps used to negotiate the terrain. With four passengers in each jeep, we passed down the rocky track, and then set out on foot for about a mile and a half, hiking near the “cloud forest” to a lookout point. The trek provided breath -taking vistas of the Andean highlands with coffee fields in the foothills. Slender wax palms, which can grow to a height of 250 feet, rose from emerald hills reaching skyward toward cloud- shrouded mountain tops. Those of us who made it to the lookout point sat there to take in the incredible scenery. The Andes are the youngest mountain range in the world, stretching from Argentina to Venezuela. The native wax palms, the world’s highest altitude palm tree, make the Colombian Andes unique.

Colombia has declared the wax palm a protected species, as it grows very slowly despite its height. We participated in a wax palm ritual by planting a seedling, which was blessed in the tradition of the local Quimbayas people. Following our active morning, we settled down to a tasty lunch of fried trout served over a very large plantain and accompanied by garlic sauce and lime juice. To drink I had mango juice, some of which I poured over the small piece of chocolate cake that arrived as dessert. Chocolate cake soaked in mango juice proved to be delicious.

Our final night in Pereira turned out to be a cooking lesson at El Avidem, a restaurant nearby. We learned how to make patacones — plantain pancakes — by blanching large chunks of the peeled and cut fruit in boiling water and then frying it in hot vegetable oil. As each fried piece took on a melon color, we placed it between sheets of wax paper and pounded it with a smooth round rock until flattened. We enjoyed this appetizer with a topping of chopped onions, scallions, and tomatoes. Wrapped in heliconia leaves and served on individual dinner plates, the main dish arrived looking like a flower ready to bloom. When peeled open, the steaming dish revealed itself — chicken tamales over rice. Dessert was platanos temtacion — plantains cut into small round shapes and cooked in syrup of cola, sugar, and cinnamon. Feeling very full, we returned to our rooms for a good night’s sleep before embarking on the last leg of our trip — Cartagena and the Caribbean coast.

(To be continued)